Humans as a species behave in interesting ways. We respond to events such as a terrorist attack, a flooding or a wildfire with some sort of intellectual answer – not always the right response but that’s a different story. On the other hand, dramatic events that affect our world as a whole and which are long lasting seem too big to fathom. Nature Climate Change

Hurricane Maria to the southeast of Puerto Rico. Source Wikimedia Commons Why is this important and what does it mean? The Gulf Stream is considered the long-distance heater of Europe, as it brings heat as far as the British Isles and off the coast of Norway. The Gulf Stream, in turn, is part of the larger Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). This carries warm and salty water northward at the ocean surface, while cold and low-salinity water flows back at depth. Based on evidence from Earth’s history, researchers suspect that the circulatory system can, in principle, switch between two different operating states: a strong circular motion, as currently observed, and a much weaker one.

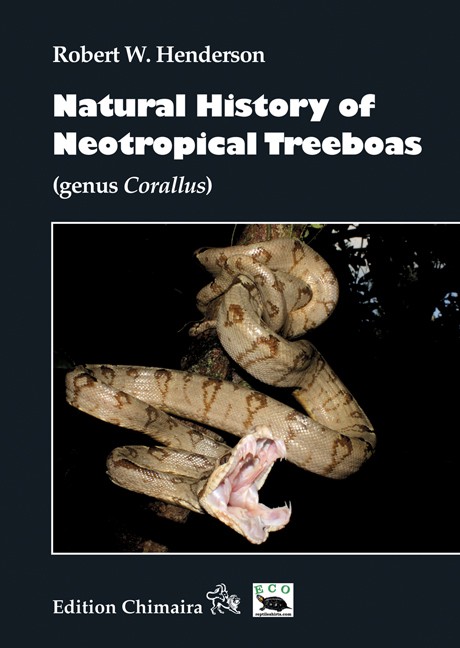

And the boas? We saw in the recent past glimpses of what hurricane intensification means for the West Indies. Hurricane Maria devastated the northeastern West Indies in September 2017, particularly Dominica (Category 5), Saint Croix, US Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico (Category 4) were affected. It is regarded as the worst natural disaster in recorded history to affect those islands. Considering the above mentioned study, we need to prepare for more of this.

Addendum On August 9th the IPCC published it’s Sixth Assessment Report

Key findings:

Global surface temperature was 1.09C higher in the last decade (2011-2020) than in the last pre industrialisation half century (1850-1900). The past five years have been the hottest on record since 1850 The recent rate of sea level rise has nearly tripled compared with 1901-1971 Human influence is “very likely” (90%) the main driver of the global retreat of glaciers since the 1990s and the decrease in Arctic sea-ice It is virtually certain that hot extremes including heatwaves have become more frequent and more intense since the 1950s, while cold events have become less frequent and less severe https://www.ipcc.ch/assessment-report/ar6/

Citations

{2129430:BDKRG2JD};{2129430:UAVV46ZD}

chicago-author-date

default

asc

0