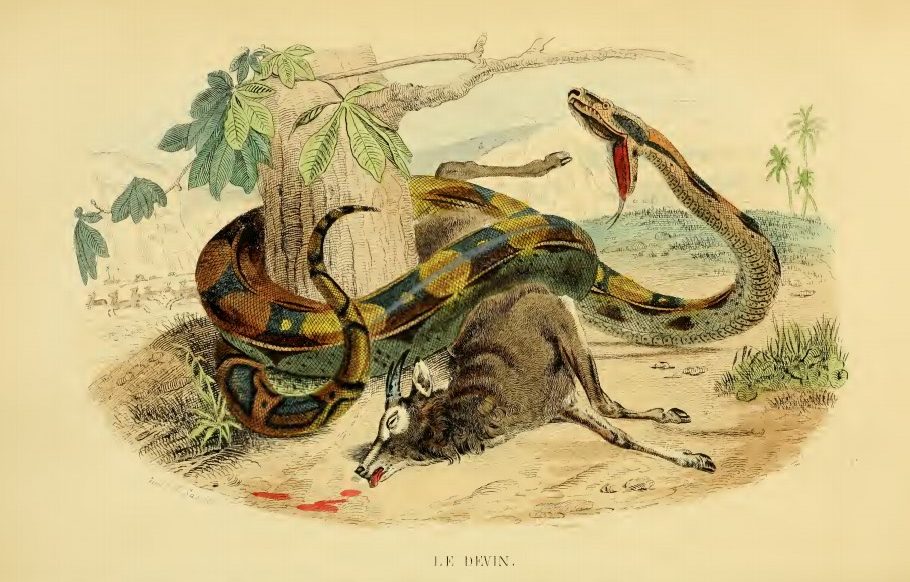

Painting, “The Liboya Serpent Seizing His Prey” by James Ward, 1803. Etymology From the Latin Boa for ‘large snake,’ after an animal mentioned in the Natural History of Pliny the Elder (AD 23-79). He was an author, naturalist and natural philosopher, a naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire.

Geographic Range The Genus Boa is restricted to the New World tropics, from northern Mexico to Argentina, and the West Indies.

Historical perspective In 1758 Linnaeus created the genus Boa; he named Boa constrictor and Boa orophias and placed them in the newly created genus. Over the next two and a half centuries scientists placed newly described boas in the genus as specimens came in from the field. Here we provide a timeline of those species and the currently recognized taxonomy of the genus. We will look a closer look at the three species, Boa constrictor , Boa nebulosa and Boa orophias in excruciating detail in each account. For now, we just present the date each species or subspecies was added to the genus Boa .

1758 Boa Boa erected]1758 Boa constrictor 1758 Boa orophias 1768 Constrictor 107 ] (Genus Constrictor erected)1768 Constrictor diviniloquus 1803 Boa imperator 151 ] [152 ]1873 Boa occidentalis 1877 Boa ortonii 1906 Epicrates sabogae 1932 Constrictor constrictor amarali 28 ] [29 ]1943 Constrictor constrictor sigma 412 ]1951 Boa constrictor imperator 1951 Boa constrictor sabogae 1951 Boa constrictor amarali 1951 Boa constrictor constrictor 1951 Boa constrictor occidentalis 1951 Boa constrictor sigma 1951 Boa orophias 1964 Boa constrictor orophias 1964 Boa constrictor nebulosa Boa constrictor orophias ]1969 Boa constrictor ortonii 1983 Boa constrictor melanogaster [Nomen dubium]1991 Boa constrictor longicauda 2007 Boa nebulosa [Elevated to full species from 1964]2007 Boa orophias [Elevated to full species from 1964]2009 Boa imperator [Elevated to full species from 1951]2016 Boa sigma [Elevated to full species from 1943]2018 Boa blanchardensis [Known only from fossil records] * 2019 Boa constrictor constrictor

* Blanchardensis refers to the holotype material found in Blanchard Cave on Marie-Galante Island; (ensis ) is a Latin adjectival suffix meaning “pertaining to” or “originating in".Boa devin. Cuvier, 1855. Taxonomy and phylogeny of the Genus Boa The taxonomy and phylogeny of the boas was a long standing question and several views have been proposed since its description. After a couple of other categorizations the current taxonomic view is that the Genus Boa forms, together with the genera Chilabothrus, Corallus, Epicrates and Eunectes, the Subfamily Boinae. The family Boidae was created by Gray almost 200 years ago

According to Pyron and coworkers, this group can be distinguished from all other taxa by the following combination of characters: internarial septum with large fenestra, anterior margin of the ventral lamina of the nasal indented in lateral view, anterolateral margin of horizontal lamina of nasal noticeably indented viewed dorsally, horizontal lamina of the nasal does not overlap dorsal surface of frontal, most of palatine process of maxilla occurs posteriorly within the orbit, anterior end of ectopterygoid consists of indistinct lateral and medial heads, supratemporal inclined slightly in lateral view, posterior end of supratemporal rounded but not dilated, arasphenoid wing large and without pedicellate ventral surface, dorsal margin of prearticular noticeably curved upward near attachment of abductor posterior muscle, cornua of hyobranchium discontinuous anteriorly, and shallow labial pits

The Genus Boa can be distinguished from the other members of the subfamily by the following dichotomous key

Q1: greatly enlarged anterior teeth? yes – Corallus no – continue to Q2Q2: eye, or circumorbitals in contact with supralabials? yes – either Epicrates or Chilabothrus no – continue to Q3Q3: Loreal large and head scalation consisting of large scales? yes – Eunectes no – Boa The molecular phylogeny within the genus has been studied, using mitochondrial genes as well as nuclear genes Boa constrictor ) and a northern clade (Boa imperator ). The study by Card and co-workers found Boa sigma is a valid taxon. Unfortunately, they did not include samples from the West Indies in their analysis. Therefore, the work from de Lima (2017) is particularly valuable, because she used many samples with known localities and included also Boa nebulosa, Boa orophias as well as Boa constrictor from Trinidad in her analysis. De Lima estimated that the origin of Boa occurred around 59.7 Mya, in the Paleocene; followed by the separation of samples from the northern and southern portions of the continent that occurred around 34.24 Mya between the Eocene and Miocene. This is in contrast to the finidings from Card et al. who suggested that the clades split about 14.5 Mya. The study by de Lima suggests further that Boa nebulosa and Boa orophias are closest related and diversified from the next clade about 0.6 Mya. Interestingly, the specimen from Trinidad appears to be different from many other Boa constrictor and forms a clade with samples from Piripiri, Belem, VitoriadoXingu, Melgaco. This clade diverged from the rest about 0.79 Mya.

Boa species on the West Indian islandsThree Boa species occur in the West Indies; subfossil records of Boa constrictor have been found on Antigua but no living specimens have been observed. Thus a population of Boa constrictor on Antigua might have existed but is considered extinct. It is unclear whether this population was of natural origin or brought in by man from other Antillean islands

In the light of recent taxonomic changes – Boa nebulosa and B. orophias were re-elevated to species level Boa species is the closest living relative. Boa orophias as well as Boa nebulosa occur on volcanic islands, whereas the majority of Chilabothrus species occurs either on coral islands or the large Antilles (tectonic shift results). This is interesting in the light of behavioral observations. Vandeventer Boa nebulosa could be found near hot steam vents. J. Murray noted that his Boa nebulosa were more heat tolerant than many other snake species and he suspected that they do need higher temperatures than other boids .

The questions of the origin of Boa on the West Indian islands remains not entirely solved. Wallace reported “a large Boa constrictor was floated to the island of St. Vincent, twisted around the trunk of a cedar tree and was so little injured by its voyage that it captured some sheep before it was killed .”

Boa constrictor can survive also further north in the West Indies, as introduced populations of Boa constrictor as well as Boa imperator on several islands of the West Indies have shown Boa constrictor from St Thomas (Virgin Islands) – “58 scales around midbody, 248 ventralia, 65 subcaudalia”. The specimen was collected by Becker 1897 Boa once existed on St. Thomas, or if the animals collected were a dispersed animal or if the collection locality was simply falsely assigned.

Furthermore, Boa species were reported from other West Indian Islands. Historical evidence from naturalists described a large snake inhabiting Martinique (the island between Saint Lucia and Dominica) Boa , however without providing further evidence other than the description of the naturalist Labat from 1724. Breuil claims that it became extinct from this island in the more distant past, since naturalists after Labat, describing the snakes from the island did not report or collect any specimens of this boa

A recent study described Boa blanchardensis , a boa species that is now extinct and inhabited Marie-Galante and possibly other Guadeloupe islands. The Boa species was described based on fossil remains. The researchers could identify differences in the osteology between Boa nebulosa and Boa blanchardensis that justified the erection of this new species. The species was most likely a dwarf species measuring between 73 mm to 139 mm based on fossil remains. The species occurred in caves which most likely reflects predation on bats. It’s extinction history is interesting in that it shows how changing climates can have large effects on species. The Boa became extinct at the beginning of the Holocene. Notably the Pleistocene-Holocene transition changed the West Indies dramatically. The island became smaller and wetter during the Holocene as a consequence of the climatic modifications occurring during this period. The authors speculate that bat biodiversity changed and bird biodiversity was also affected and thus, a general rarefaction of prey may have had a strong impact on B. blanchardensis leading to its extinction on Marie-Galante

Evolution Fossil remains of Boa are not particularly rare and have been found from various sites e.g. 55 to 51 Mya) on the South American mainland. However these were only tentatively assigned to the genus Boa , because of the deficient preservation status

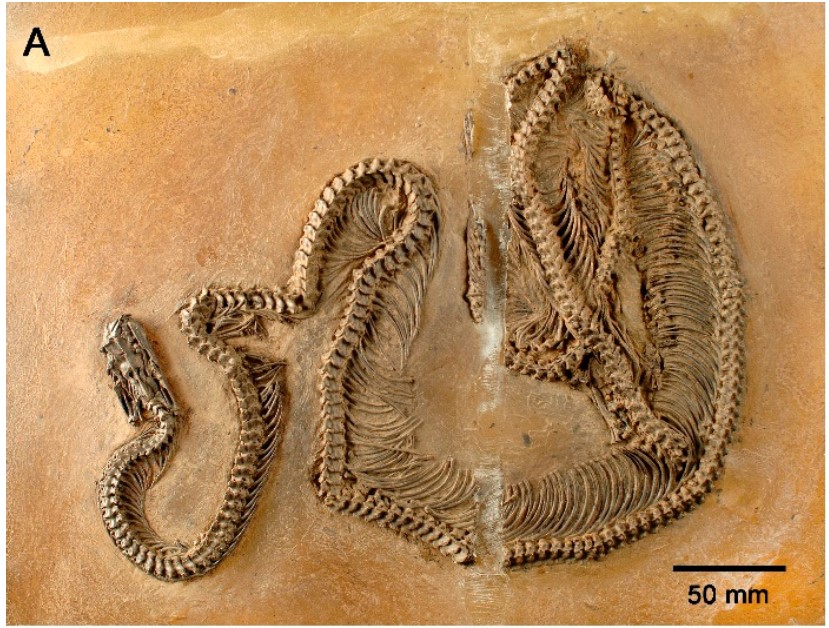

The study of several exquisitely preserved skeletons of the booid snake Eoconstrictor fischeri from the Eocene Konservat-Lagerstätte of Messel, Germany provides considerable new insight into the biology of early boas (E. fisheri is the only species in the genus; all known specimens come from the Middle Messel Formation (ibid).

Eoconstrictor fischeri from early-middle Eocene, about 48 Ma. (Schaal, 2004) Species Boa constrictor – This species has a wide distribution in Latin america. In the West Indies region, it occurs only on Trinidad and Tobago, adjacent to the Venezuelan coast of mainland Latin America. The conservation status of Boa constrictor on Trinidad and Tobago is not clearly assessed. Boa constrictor has a long and successful history in terraria worldwide. Boa imperator Boa nebulosa Boa orophias Boa sigma B. imperator. The Western Mexico lineage has recently been elevated to full species status by Card and co-workers Boa sigma a valid species.Boa species in vivariaAll Boa species have been kept in terraria with good success. The two insular forms B. nebulosa and B. orophias are unfortunately not as popular among hobbyists and in addition proved to be more difficult to keep. Therefore the Common Boa and the Emperor Boa are bred in large numbers in captivity, whereas the Clouded Boa and the St. Lucia Boa have almost entirely vanished from terraria.

Continue to Boa constrictor Citations

{2129430:L8Z4EX9H};{2129430:TG752CN3};{2129430:H9BX966A},{2129430:7ZTUJVPE},{2129430:U5YULRJW};{2129430:T4WFLTGY},{2129430:SZ5RJZQN};{2129430:YSSGA26J};{2129430:AYUQF2G4};{2129430:V6QGWM7Z};{2129430:D662M6QL},{2129430:JGSWHCJF},{2129430:HBAWCUBU};{2129430:BFB8KQ43};{2129430:LBGADMLZ};{2129430:AZHPH7YL};{2129430:U8H4FW87};{2129430:N87VUQTW};{2129430:PW7DQX8Y},{2129430:YWDNBRBA};{2129430:U4CZLY5D};{2129430:I7AINDKS};{2129430:QLMRP7YB};{2129430:7ZTUJVPE}

apa

author

asc

no

27 %7B%22status%22%3A%22success%22%2C%22updateneeded%22%3Afalse%2C%22instance%22%3A%22zotpress-c35816cad11e491cef191a3a971d7276%22%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22request_last%22%3A0%2C%22request_next%22%3A0%2C%22used_cache%22%3Atrue%7D%2C%22data%22%3A%5B%7B%22key%22%3A%22U4CZLY5D%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Albino%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221993%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EAlbino%2C%20A.%20M.%20%281993%29.%20Snakes%20from%20the%20Paleocene%20and%20Eocene%20of%20Patagonia%20%28Argentina%29%3A%20Paleoecology%20and%20coevolution%20with%20mammals.%20%3Ci%3EHistorical%20Biology%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E7%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%281%29%2C%2051%26%23x2013%3B69.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1080%5C%2F10292389309380443%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1080%5C%2F10292389309380443%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Snakes%20from%20the%20Paleocene%20and%20Eocene%20of%20Patagonia%20%28Argentina%29%3A%20Paleoecology%20and%20coevolution%20with%20mammals%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Adriana%20Maria%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Albino%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%2207%5C%2F1993%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.1080%5C%2F10292389309380443%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220891-2963%2C%201029-2381%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.tandfonline.com%5C%2Fdoi%5C%2Fabs%5C%2F10.1080%5C%2F10292389309380443%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-10-05T21%3A01%3A20Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22PW7DQX8Y%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Albino%20and%20Carlini%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222008%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EAlbino%2C%20A.%20M.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Carlini%2C%20A.%20A.%20%282008%29.%20First%20Record%20of%20Boa%20Constrictor%20%28Serpentes%2C%20Boidae%29%20in%20the%20Quaternary%20of%20South%20America.%20%3Ci%3EJournal%20of%20Herpetology%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E42%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%281%29%2C%2082%26%23x2013%3B88.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1670%5C%2F07-124R1.1%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1670%5C%2F07-124R1.1%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22First%20Record%20of%20Boa%20Constrictor%20%28Serpentes%2C%20Boidae%29%20in%20the%20Quaternary%20of%20South%20America%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Adriana%20M.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Albino%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Alfredo%20A.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Carlini%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Vertebral%20remains%20assignable%20to%20the%20extant%20snake%20Boa%20constrictor%2C%20found%20in%20the%20Torop%5Cu00b4%5Cu0131%20Formation%20%28Late%20Pleistocene%2C%20Lujanian%20age%29%20at%20Arroyo%20Torop%5Cu00b4%5Cu0131%2C%20northeastern%20Argentina%2C%20are%20here%20described.%20These%20remains%20represent%20the%20first%20snake%20record%20from%20the%20Lujanian%20age%20and%20determine%20the%20minimum%20age%20for%20the%20species%20as%2050%5Cu201335%20ka%20BP.%20Boa%20is%20presently%20absent%20in%20northeastern%20Argentina.%20Interruption%20of%20the%20continuity%20between%20the%20Mesopotamian%20and%20Brazilian%20faunas%2C%20including%20disappearance%20of%20Boa%20from%20Mesopotamia%20%28northeastern%20Argentina%29%2C%20occurred%20subsequent%20to%20the%20Late%20Pleistocene%20and%20might%20be%20explained%20by%20changes%20in%20the%20Parana%5Cu00b4%20and%20Uruguay%20Rivers.%20In%20addition%2C%20previous%20taxonomic%20referral%20of%20fossils%20to%20%3FBoa%20is%20revised%2C%20with%20the%20conclusion%20that%20the%20specimen%20from%20the%20Early%20Eocene%20is%20tentatively%20referred%20to%20this%20genus%2C%20whereas%20that%20from%20the%20Pliocene%20is%20an%20indeterminate%20Boinae.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%2203%5C%2F2008%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.1670%5C%2F07-124R1.1%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220022-1511%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.bioone.org%5C%2Fdoi%5C%2Fabs%5C%2F10.1670%5C%2F07-124R1.1%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-08-04T21%3A45%3A52Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22N87VUQTW%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Bochaton%20and%20Bailon%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222018-05-04%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A2%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EBochaton%2C%20C.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Bailon%2C%20S.%20%282018%29.%20A%20new%20fossil%20species%20of%20%3Ci%3EBoa%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%20Linnaeus%2C%201758%20%28Squamata%2C%20Boidae%29%2C%20from%20the%20Pleistocene%20of%20Marie-Galante%20Island%20%28French%20West%20Indies%29.%20%3Ci%3EJournal%20of%20Vertebrate%20Paleontology%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E38%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%283%29%2C%20e1462829.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1080%5C%2F02724634.2018.1462829%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1080%5C%2F02724634.2018.1462829%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22A%20new%20fossil%20species%20of%20%3Ci%3EBoa%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%20Linnaeus%2C%201758%20%28Squamata%2C%20Boidae%29%2C%20from%20the%20Pleistocene%20of%20Marie-Galante%20Island%20%28French%20West%20Indies%29%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Corentin%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Bochaton%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Salvador%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Bailon%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Several%20studies%20have%20reported%20the%20occurrence%20of%20fossil%20remains%20of%20a%20now%20extinct%20Boa%20snake%20from%20the%20upper%20Pleistocene%20of%20Marie-Galante%20Island%2C%20French%20West%20Indies.%20However%2C%20these%20remains%20have%20never%20been%20fully%20investigated%20and%20no%20complete%20description%20of%20this%20possible%20new%20species%20has%20been%20published.%20In%20this%20paper%2C%20we%20try%20to%20bridge%20this%20gap%20by%20providing%20a%20detailed%20morphological%20study%20of%20the%20Boa%20remains%20discovered%20in%20the%20three%20major%20fossil%20deposits%20of%20Marie-Galante%20Island.%20Our%20study%20reveals%20the%20speci%5Cufb01c%20morphological%20aspects%20of%20this%20fossil%20snake%20and%20allows%20us%20to%20identify%20it%20as%20a%20new%20species%2C%20Boa%20blanchardensis.%20We%20also%20reconstructed%20its%20body%20size%2C%20carried%20out%20a%20paleohistological%20investigation%2C%20and%20suggest%20that%20this%20snake%20may%20have%20been%20a%20dwarf%20species.%20We%20then%20discuss%20the%20possible%20explanation%20for%20the%20extinction%20of%20this%20snake%20on%20Marie-Galante%20Island%20and%20possibly%20also%20on%20other%20Guadeloupe%20islands.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222018-05-04%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.1080%5C%2F02724634.2018.1462829%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220272-4634%2C%201937-2809%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.tandfonline.com%5C%2Fdoi%5C%2Ffull%5C%2F10.1080%5C%2F02724634.2018.1462829%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-10-05T16%3A09%3A47Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22YSSGA26J%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Bonny%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222007%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EBonny%2C%20K.%20%282007%29.%20%3Ci%3EDie%20Gattung%20Boa%3A%20Taxonomie%20und%20Fortpflanzung%3C%5C%2Fi%3E.%20Kirschner%20%26amp%3B%20Seufer.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Die%20Gattung%20Boa%3A%20Taxonomie%20und%20Fortpflanzung%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Klaus%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Bonny%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222007%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22German%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22978-3-9808264-5-7%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-02-28T10%3A03%3A49Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22U8H4FW87%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Breuil%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222009%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EBreuil%2C%20M.%20%282009%29.%20The%20terrestrial%20herpetofauna%20of%20Martinique%3A%20Past%2C%20present%2C%20future.%20%3Ci%3EApplied%20Herpetology%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E6%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%282%29%2C%20123%26%23x2013%3B149.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1163%5C%2F157075408X386114%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1163%5C%2F157075408X386114%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22The%20terrestrial%20herpetofauna%20of%20Martinique%3A%20Past%2C%20present%2C%20future%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Michel%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Breuil%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22I%20present%20an%20up-to-date%20annotated%20list%20of%20the%20herpetofauna%20of%20Martinique%2C%20and%20try%20to%20explain%20the%20causes%20responsible%20for%20the%20eradication%20of%20species%20such%20as%20Leptodactylus%20fallax%2C%20Boa%20sp.%20and%20Leiocephalus%20herminieri.%20Mabuya%20mabouya%20and%20Liophis%20cursor%20have%20not%20been%20seen%20for%20decades%20and%20may%20have%20been%20extirpated.%20It%20cannot%20be%20established%20that%20the%20mongoose%20was%20responsible%3B%20Didelphis%20marsupialis%2C%20of%20recent%20introduction%2C%20may%20have%20played%20an%20important%20role.%20Introduced%20and%20invasive%20species%20are%20numerous%20in%20Martinique%3A%20Chaunus%20marinus%2C%20Scinax%20ruber%2C%20Eleutherodactylus%20johnstonei%2C%20Gymnophthalmus%20underwoodi%2C%20Iguana%20iguana%2C%20Gekko%20gecko%2C%20Hemidactylus%20mabouia%2C%20without%20considering%20escaped%20pets%20and%20the%20dubious%20case%20of%20Allobates%20chalcopis%20as%20an%20endemic%20species.%20I%20also%20present%20the%20restoration%20plan%20for%20Iguana%20delicatissima%20in%20the%20French%20West%20Indies%20and%20the%20conservation%20work%20for%20this%20species%20in%20Martinique%3B%20increase%20of%20nesting%20areas%2C%20translocation%2C%20creation%20of%20numerous%20protected%20areas%2C%20and%20control%20of%20I.%20iguana.%20Of%20a%20total%20of%2013%20endemic%20and%20indigenous%20species%20from%20Martinique%2C%20three%20are%20de%5Cufb01nitely%20and%20a%20further%20two%20are%20probably%20eradicated.%20Including%20Guadeloupe%2C%20the%20French%20West%20Indies%20have%20the%20highest%20loss%20of%20herpetological%20biodiversity%20among%20all%20the%20islands%20in%20the%20West%20Indies.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222009%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.1163%5C%2F157075408X386114%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%221570-7539%2C%201570-7547%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fbrill.com%5C%2Fview%5C%2Fjournals%5C%2Fah%5C%2F6%5C%2F2%5C%2Farticle-p123.xml%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-10-05T16%3A26%3A20Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22D662M6QL%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Bushar%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222015%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EBushar%2C%20L.%20M.%2C%20Reynolds%2C%20R.%20G.%2C%20Tucker%2C%20S.%2C%20Pace%2C%20L.%20C.%2C%20Lutterschmidt%2C%20W.%20I.%2C%20Odum%2C%20R.%20A.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Reinert%2C%20H.%20K.%20%282015%29.%20Genetic%20Characterization%20of%20an%20Invasive%20%3Ci%3EBoa%20constrictor%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%20Population%20on%20the%20Caribbean%20Island%20of%20Aruba.%20%3Ci%3EJournal%20of%20Herpetology%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E49%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%284%29%2C%20602%26%23x2013%3B610.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1670%5C%2F14-059%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1670%5C%2F14-059%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Genetic%20Characterization%20of%20an%20Invasive%20%3Ci%3EBoa%20constrictor%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%20Population%20on%20the%20Caribbean%20Island%20of%20Aruba%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Lauretta%20M.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Bushar%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22R.%20Graham%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Reynolds%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Sharese%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Tucker%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22LaCoya%20C.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Pace%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22William%20I.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Lutterschmidt%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22R.%20Andrew%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Odum%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Howard%20K.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Reinert%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%2212%5C%2F2015%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.1670%5C%2F14-059%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220022-1511%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.bioone.org%5C%2Fdoi%5C%2F10.1670%5C%2F14-059%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-03-10T01%3A12%3A27Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%227ZTUJVPE%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Card%20DC%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222016%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A2%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3ECard%20DC%2C%20Schield%20DR%2C%20Adams%20RH%2C%20Corbin%20AB%2C%20Perry%20BW%2C%20Andrew%20AL%2C%20Pasquesi%20GI%2C%20Smith%20EN%2C%20Jezkova%20T%2C%20Boback%20SM%2C%20Booth%20W%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Castoe%20TA.%20%282016%29.%20Phylogeographic%20and%20population%20genetic%20analyses%20reveal%20multiple%20species%20of%20Boa%20and%20independent%20origins%20of%20insular%20dwarfism.%20%3Ci%3EMolecular%20Phylogenetics%20and%20Evolution%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E102%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20104%26%23x2013%3B116.%20%5C%2Fz-wcorg%5C%2F.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Phylogeographic%20and%20population%20genetic%20analyses%20reveal%20multiple%20species%20of%20Boa%20and%20independent%20origins%20of%20insular%20dwarfism.%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Card%20DC%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Schield%20DR%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Adams%20RH%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Corbin%20AB%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Perry%20BW%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Andrew%20AL%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Pasquesi%20GI%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Smith%20EN%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Jezkova%20T%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Boback%20SM%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Booth%20W%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Castoe%20TA%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Boa%20is%20a%20Neotropical%20genus%20of%20snakes%20historically%20recognized%20as%20monotypic%20despite%20its%20expansive%20distribution.%20The%20distinct%20morphological%20traits%20and%20color%20patterns%20exhibited%20by%20these%20snakes%2C%20together%20with%20the%20wide%20diversity%20of%20ecosystems%20they%20inhabit%2C%20collectively%20suggest%20that%20the%20genus%20may%20represent%20multiple%20species.%20Morphological%20variation%20within%20Boa%20also%20includes%20instances%20of%20dwarfism%20observed%20in%20multiple%20offshore%20island%20populations.%20Despite%20this%20substantial%20diversity%2C%20the%20systematics%20of%20the%20genus%20Boa%20has%20received%20little%20attention%20until%20very%20recently.%20In%20this%20study%20we%20examined%20the%20genetic%20structure%20and%20phylogenetic%20relationships%20of%20Boa%20populations%20using%20mitochondrial%20sequences%20and%20genome-wide%20SNP%20data%20obtained%20from%20RADseq.%20We%20analyzed%20these%20data%20at%20multiple%20geographic%20scales%20using%20a%20combination%20of%20phylogenetic%20inference%20%28including%20coalescent-based%20species%20delimitation%29%20and%20population%20genetic%20analyses.%20We%20identified%20extensive%20population%20structure%20across%20the%20range%20of%20the%20genus%20Boa%20and%20multiple%20lines%20of%20evidence%20for%20three%20widely-distributed%20clades%20roughly%20corresponding%20with%20the%20three%20primary%20land%20masses%20of%20the%20Western%20Hemisphere.%20We%20also%20find%20both%20mitochondrial%20and%20nuclear%20support%20for%20independent%20origins%20and%20parallel%20evolution%20of%20dwarfism%20on%20offshore%20island%20clusters%20in%20Belize%20and%20Cayos%20Cochinos%20Menor%2C%20Honduras.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222016%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22English%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%221055-7903%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-11-10T14%3A22%3A09Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22SZ5RJZQN%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Daltry%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222007%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EDaltry%2C%20J.%20C.%20%282007%29.%20An%20introduction%20to%20the%20herpetofauna%20of%20Antigua%2C%20Barbuda%20and%20Redonda%2C%20with%20some%20conservation%20recommendations.%20%3Ci%3EAPPLIED%20HERPETOLOGY%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E4%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%282%29%2C%2097%26%23x2013%3B130.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22An%20introduction%20to%20the%20herpetofauna%20of%20Antigua%2C%20Barbuda%20and%20Redonda%2C%20with%20some%20conservation%20recommendations%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Jennifer%20C%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Daltry%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22At%20least%2029%20reptiles%20and%20amphibians%20have%20been%20documented%20on%20Antigua%2C%20Barbuda%20and%20Redonda%2C%20of%20which%2021%20are%20probably%20native.%20These%20include%20four%20species%20of%20marine%20turtles%2C%20two%20of%20which%20%28Eretmochelys%20imbricata%20and%20Chelonia%20mydas%29%20are%20known%20to%20nest%20on%20the%20nation%5Cu2019s%20numerous%20sandy%20beaches%20and%20forage%20in%20nearshore%20waters.%20The%20low-lying%20and%20largely%20sedimentary%20islands%20of%20Antigua%20%28280%20km2%29%20and%20Barbuda%20%28161%20km2%29%20formed%20a%20single%20island%20as%20recently%20as%2012%2C000%20years%20ago%20and%20exhibit%20a%20similar%20herpetofauna%20with%20high%20endemicity.%20At%20least%20four%20terrestrial%20species%20are%20endemic%20to%20the%20Antigua%20and%20Barbuda%20bank%3A%20Alsophis%20antiguae%2C%20Ameiva%20griswoldi%2C%20Anolis%20wattsi%2C%20Sphaerodactylus%20elegantulus%20%28a%20possible%20%5Cufb01fth%20being%20Barbuda%5Cu2019s%20Anolis%20forresti%2C%20if%20not%20synonymous%20with%20A%20wattsi%29%2C%20and%20a%20further%20%5Cufb01ve%20are%20Lesser%20Antillean%20endemics.%20Only%20six%20species%20have%20been%20documented%20on%20the%20small%2C%20rugged%20volcanic%20island%20of%20Redonda%20%281%20km2%29%2C%20but%20as%20many%20as%20half%20of%20them%20occur%20nowhere%20else%20%28Ameiva%20atrata%2C%20Anolis%20nubilus%2C%20and%20a%20potentially%20new%20Sphaerodactylus%20sp.%29.%20Centuries%20of%20forest%20clearance%2C%20overgrazing%20and%20development%2C%20coupled%20with%20the%20introduction%20of%20small%20Asian%20mongooses%20%28Herpestes%20javanicus%29%2C%20black%20rats%20%28Rattus%20rattus%29%20and%20other%20alien%20invasive%20species%2C%20has%20endangered%20many%20of%20the%20nation%5Cu2019s%20wildlife%2C%20and%20at%20least%20four%20indigenous%20reptiles%20have%20been%20extirpated%20%28Boa%20constrictor%2C%20Clelia%20clelia%2C%20Iguana%20delicatissima%2C%20and%20Leiocephalus%20cuneus%29.%20Recent%20moves%20to%20enlarge%20the%20nation%5Cu2019s%20protected%20area%20network%20are%20encouraging%2C%20but%20need%20to%20be%20supported%20with%20stronger%20legislation%20and%20proper%20investment%20in%20management%20staff%20and%20resources.%20This%20paper%20presents%20conservation%20recommendations%20and%20describes%20two%20projects%20that%20have%20adopted%20innovative%20approaches%20to%20save%20the%20most%20critically%20endangered%20reptiles%20%5Cu2014the%20Jumby%20Bay%20Hawksbill%20Project%20and%20the%20Antiguan%20Racer%20Conservation%20Project.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222007%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-07-16T17%3A57%3A34Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22U5YULRJW%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22de%20Lima%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222017-06-26%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3Ede%20Lima%2C%20L.%20C.%20B.%20%282017%29.%20%3Ci%3EFilogenia%20e%20delimita%26%23xE7%3B%26%23xE3%3Bo%20de%20esp%26%23xE9%3Bcies%20no%20complexo%20Boa%20constrictor%20%28Serpentes%2C%20Boidae%29%20utilizando%20marcadores%20moleculares%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%20%5BDoutorado%20em%20Biologia%2C%20Universidade%20de%20S%26%23xE3%3Bo%20Paulo%5D.%20https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.11606%5C%2FT.41.2017.tde-26052017-112144%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22thesis%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Filogenia%20e%20delimita%5Cu00e7%5Cu00e3o%20de%20esp%5Cu00e9cies%20no%20complexo%20Boa%20constrictor%20%28Serpentes%2C%20Boidae%29%20utilizando%20marcadores%20moleculares%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Lorena%20Corina%20Bezerra%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22de%20Lima%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22thesisType%22%3A%22Doutorado%20em%20Biologia%22%2C%22university%22%3A%22Universidade%20de%20S%5Cu00e3o%20Paulo%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222017-6-26%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.teses.usp.br%5C%2Fteses%5C%2Fdisponiveis%5C%2F41%5C%2F41131%5C%2Ftde-26052017-112144%5C%2F%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222023-05-30T22%3A09%3A07Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22HBAWCUBU%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Golden%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222017%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EGolden%2C%20I.%20%282017%29.%20Origin%20of%20the%20Invasive%20Boa%20Constrictor%20population%20in%20St.%20Croix%2C%20U.S.%20Virgin%20Islands.%20%3Ci%3EProceedings%20of%20The%20National%20Conferences%20On%20Undergraduate%20Research%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20864%26%23x2013%3B869.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Origin%20of%20the%20Invasive%20Boa%20Constrictor%20population%20in%20St.%20Croix%2C%20U.S.%20Virgin%20Islands%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Israel%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Golden%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222017%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-07-16T21%3A57%3A33Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22L8Z4EX9H%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Gray%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221825%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A2%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EGray%2C%20J.%20E.%20%281825%29.%20A%20Synopsis%20of%20the%20genera%20of%20Reptiles%20and%20Amphibia%2C%20with%20a%20description%20of%20some%20new%20species.%20%3Ci%3EAnnals%20of%20Philosophy.%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3En.s.%20v.%2010%20%281825%29%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20193%26%23x2013%3B217.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.biodiversitylibrary.org%5C%2Fpart%5C%2F218438%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.biodiversitylibrary.org%5C%2Fpart%5C%2F218438%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22A%20Synopsis%20of%20the%20genera%20of%20Reptiles%20and%20Amphibia%2C%20with%20a%20description%20of%20some%20new%20species.%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22John%20Edward%2C%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Gray%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221825%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.biodiversitylibrary.org%5C%2Fpart%5C%2F218438%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-11-10T10%3A58%3A06Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22H9BX966A%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Hynkov%5Cu00e1%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222009%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EHynkov%26%23xE1%3B%2C%20I.%2C%20Starostov%26%23xE1%3B%2C%20Z.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Frynta%2C%20D.%20%282009%29.%20Mitochondrial%20DNA%20Variation%20Reveals%20Recent%20Evolutionary%20History%20of%20Main%20%3Ci%3EBoa%20constrictor%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%20Clades.%20%3Ci%3EZoological%20Science%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E26%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%289%29%2C%20623%26%23x2013%3B631.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.2108%5C%2Fzsj.26.623%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.2108%5C%2Fzsj.26.623%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Mitochondrial%20DNA%20Variation%20Reveals%20Recent%20Evolutionary%20History%20of%20Main%20%3Ci%3EBoa%20constrictor%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%20Clades%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Ivana%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Hynkov%5Cu00e1%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Zuzana%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Starostov%5Cu00e1%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Daniel%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Frynta%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%2209%5C%2F2009%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.2108%5C%2Fzsj.26.623%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220289-0003%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.bioone.org%5C%2Fdoi%5C%2Fabs%5C%2F10.2108%5C%2Fzsj.26.623%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-03-24T13%3A16%3A52Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22AZHPH7YL%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Labat%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221717%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3ELabat%2C%20J.-B.%20%281717%29.%20%3Ci%3EVoyage%20du%20P%26%23xE8%3Bre%20Labat%2C%20aux%20isles%20de%20l%26%23x2019%3BAm%26%23xE9%3Brique%20contenant%3A%20une%20exacte%20description%20de%20toutes%20ces%20isles%3B%20des%20arbres%2C%20plantes%2C%20fleurs%20et%20fruits%20qu%26%23x2019%3Belles%20produisent%3B%20des%20animaux%2C%20oiseaux%2C%20reptiles%20et%20poissons%20qu%26%23x2019%3Bon%20y%20trouve%3B%20des%20habitants%2C%20de%20leurs%20moeurs%20et%20cout%26%23xFB%3Bmes%2C%20des%20manufactures%20et%20du%20commerce%20qu%26%23x2019%3Bon%20y%20fait%20etc.%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%20P.%20Lusson%20et%20al.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Voyage%20du%20P%5Cu00e8re%20Labat%2C%20aux%20isles%20de%20l%5Cu2019Am%5Cu00e9rique%20contenant%3A%20une%20exacte%20description%20de%20toutes%20ces%20isles%3B%20des%20arbres%2C%20plantes%2C%20fleurs%20et%20fruits%20qu%5Cu2019elles%20produisent%3B%20des%20animaux%2C%20oiseaux%2C%20reptiles%20et%20poissons%20qu%5Cu2019on%20y%20trouve%3B%20des%20habitants%2C%20de%20leurs%20moeurs%20et%20cout%5Cu00fbmes%2C%20des%20manufactures%20et%20du%20commerce%20qu%5Cu2019on%20y%20fait%20etc.%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22J-B%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Labat%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221717%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-12-15T08%3A48%3A05Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22LBGADMLZ%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Meerwarth%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221901%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A2%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EMeerwarth%2C%20H.%20%281901%29.%20Die%20westindischen%20Reptilien%20und%20Batrachier%20des%20naturhistorischen%20Museums%20in%20Hamburg.%20%3Ci%3EMittheilungen%20Des%20Naturhistorischen%20Museums%20Hamburg%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E18%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%201%26%23x2013%3B41.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Die%20westindischen%20Reptilien%20und%20Batrachier%20des%20naturhistorischen%20Museums%20in%20Hamburg%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Herrman%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Meerwarth%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221901%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-08-18T09%3A15%3A03Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22YWDNBRBA%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Onary-Alves%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222017-01-02%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EOnary-Alves%2C%20S.%20Y.%2C%20Hsiou%2C%20A.%20S.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Rinc%26%23xF3%3Bn%2C%20A.%20D.%20%282017%29.%20The%20northernmost%20South%20American%20fossil%20record%20of%20%3Ci%3EBoa%20constrictor%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%20%28Boidae%2C%20Boinae%29%20from%20the%20Plio%26%23x2013%3BPleistocene%20of%20El%20Breal%20de%20Orocual%20%28Venezuela%29.%20%3Ci%3EAlcheringa%3A%20An%20Australasian%20Journal%20of%20Palaeontology%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E41%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%281%29%2C%2061%26%23x2013%3B68.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1080%5C%2F03115518.2016.1180031%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1080%5C%2F03115518.2016.1180031%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22The%20northernmost%20South%20American%20fossil%20record%20of%20%3Ci%3EBoa%20constrictor%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%20%28Boidae%2C%20Boinae%29%20from%20the%20Plio%5Cu2013Pleistocene%20of%20El%20Breal%20de%20Orocual%20%28Venezuela%29%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Silvio%20Y.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Onary-Alves%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Annie%20S.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Hsiou%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Ascanio%20D.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Rinc%5Cu00f3n%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Silvio%20Y.%20Onary-Alves%20%5Bsilvioyuji%40gmail.com%5D%2C%20Programa%20de%20P%5Cu00f3s-gradua%5Cu00e7%5Cu00e3o%20em%20Biologia%20Comparada%2C%20Faculdade%20de%20Filoso%5Cufb01a%2C%20Ci%5Cu00eancias%20e%20Letras%2C%20Universidade%20de%20S%5Cu00e3o%20Paulo%20%28USP%29%2C%20Av.%20Bandeirantes%203900%2C%20CEP%2014040901%2C%20Ribeir%5Cu00e3o%20Preto%2C%20S%5Cu00e3o%20Paulo%2C%20Brazil%3B%20Annie%20S.%20Hsiou%20%5Banniehsiou%40ffclrp.usp.br%5D%2C%20Laborat%5Cu00f3rio%20de%20Paleontologia%2C%20Faculdade%20de%20Filoso%5Cufb01a%2C%20Ci%5Cu00eancias%20e%20Letras%2C%20Departamento%20de%20Biologia%2C%20Universidade%20de%20S%5Cu00e3o%20Paulo%20%28USP%29%2C%20Av.%20Bandeirantes%203900%2C%20CEP%2014040901%2C%20Ribeir%5Cu00e3o%20Preto%2C%20S%5Cu00e3o%20Paulo%2C%20Brazil%3B%20Ascanio%20D.%20Rinc%5Cu00f3n%20%5Bpaleosur1974%40gmail.%20com%5D%2C%20Laboratorio%20de%20Paleontolog%5Cu00eda%2C%20Centro%20de%20Ecolog%5Cu00eda%2C%20Instituto%20Venezolano%20de%20Investigaciones%20Cient%5Cu00ed%5Cufb01cas%20%28IVIC%29%2C%20Carretera%20Panamericana%20Km%2011%2C%201020-A%20Caracas%2C%20Venezuela.%20Received%2010.1.2016%3B%20revised%2017.3.2016%3B%20accepted%2014.4.2016.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222017-01-02%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.1080%5C%2F03115518.2016.1180031%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220311-5518%2C%201752-0754%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.tandfonline.com%5C%2Fdoi%5C%2Ffull%5C%2F10.1080%5C%2F03115518.2016.1180031%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-08-11T18%3A13%3A16Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22TG752CN3%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Pyron%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222014-08-01%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A7%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EPyron%2C%20R.%20A.%2C%20Reynolds%2C%20R.%20G.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Burbrink%2C%20F.%20T.%20%282014%29.%20A%20Taxonomic%20Revision%20of%20Boas%20%28Serpentes%3A%20Boidae%29.%20%3Ci%3EZootaxa%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E3846%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%282%29%2C%20249.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.11646%5C%2Fzootaxa.3846.2.5%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.11646%5C%2Fzootaxa.3846.2.5%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22A%20Taxonomic%20Revision%20of%20Boas%20%28Serpentes%3A%20Boidae%29%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22R.%20Alexander%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Pyron%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22R.%20Graham%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Reynolds%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Frank%20T.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Burbrink%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222014-08-01%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.11646%5C%2Fzootaxa.3846.2.5%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%221175-5334%2C%201175-5326%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fbiotaxa.org%5C%2FZootaxa%5C%2Farticle%5C%2Fview%5C%2Fzootaxa.3846.2.5%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-09-18T22%3A00%3A35Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22BFB8KQ43%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Quick%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222005%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EQuick%2C%20J.%20S.%2C%20Reinert%2C%20H.%20K.%2C%20de%20Cuba%2C%20E.%20R.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Odum%2C%20R.%20A.%20%282005%29.%20Recent%20Occurrence%20and%20Dietary%20Habits%20of%20Boa%20constrictor%20on%20Aruba%2C%20Dutch%20West%20Indies.%20%3Ci%3EJournal%20of%20Herpetology%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E39%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%282%29%2C%20304%26%23x2013%3B307.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1670%5C%2F45-04N%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1670%5C%2F45-04N%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Recent%20Occurrence%20and%20Dietary%20Habits%20of%20Boa%20constrictor%20on%20Aruba%2C%20Dutch%20West%20Indies%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22John%20S.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Quick%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Howard%20K.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Reinert%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Eric%20R.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22de%20Cuba%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22R.%20Andrew%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Odum%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Boa%20constrictor%20was%20%5Cufb01rst%20documented%20on%20the%20island%20of%20Aruba%20in%20April%20of%201999.%20By%20the%20end%20of%20December%2C%202003%2C%20273%20B.%20constrictor%20had%20been%20captured.%20These%20snakes%20ranged%20in%20size%20from%20neonates%20%280.30%20m%20total%20length%29%20to%20large%20adults%20%282.8%20m%20total%20length%29%20and%20included%20at%20least%20two%20gravid%20females.%20Boa%20constrictor%20is%20currently%20distributed%20islandwide%20with%20the%20highest%20frequency%20of%20occurrence%20in%20the%20southern%20and%20southeastern%20portions%20of%20the%20island.%20The%20increasing%20frequency%20of%20occurrence%2C%20extensive%20distribution%2C%20and%20size%20diversity%20of%20B.%20constrictor%20indicate%20that%20a%20large%2C%20reproductively%20successful%20population%20is%20established%20on%20Aruba.%20The%20diet%20of%20the%20B.%20constrictor%20on%20Aruba%20was%20determined%20from%20the%20examination%20of%20stomach%20content%20and%20scat%20samples%20%28N%205%2047%29.%20Birds%20comprised%2040.4%25%2C%20lizards%2034.6%25%20and%20mammals%2025.0%25%20of%2052%20separate%20prey%20items%20identi%5Cufb01ed.%20A%20correlation%20was%20found%20between%20snake%20total%20length%20and%20prey%20mass%20%28r%2828%29%205%200.49%2C%20P%20%2C%200.01%29%20suggesting%20an%20ontogenetic%20shift%20in%20the%20diet%20at%20a%20total%20length%20of%20approximately%201.0%20m.%20In%20view%20of%20the%20diverse%20diet%20and%20increasing%20population%20of%20B.%20constrictor%2C%20there%20is%20concern%20about%20the%20potential%20impact%20of%20this%20invasive%20predator%20on%20the%20Aruban%20fauna.%20A%20government%20instituted%20euthanization%20program%20for%20all%20captured%20B.%20constrictor%20has%20proven%20ineffective%20at%20controlling%20the%20population.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%2206%5C%2F2005%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.1670%5C%2F45-04N%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220022-1511%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.bioone.org%5C%2Fdoi%5C%2Fabs%5C%2F10.1670%5C%2F45-04N%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-07-19T11%3A09%3A13Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22JGSWHCJF%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Reynolds%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222013%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A12%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EReynolds%2C%20R.%20G.%2C%20Puente-Rol%26%23xF3%3Bn%2C%20A.%20R.%2C%20Reed%2C%20R.%20N.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Revell%2C%20L.%20J.%20%282013%29.%20Genetic%20analysis%20of%20a%20novel%20invasion%20of%20Puerto%20Rico%20by%20an%20exotic%20constricting%20snake.%20%3Ci%3EBiological%20Invasions%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E15%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%285%29%2C%20953%26%23x2013%3B959.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1007%5C%2Fs10530-012-0354-2%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1007%5C%2Fs10530-012-0354-2%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Genetic%20analysis%20of%20a%20novel%20invasion%20of%20Puerto%20Rico%20by%20an%20exotic%20constricting%20snake%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22R.%20Graham%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Reynolds%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Alberto%20R.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Puente-Rol%5Cu00f3n%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Robert%20N.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Reed%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Liam%20J.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Revell%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%225%5C%2F2013%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.1007%5C%2Fs10530-012-0354-2%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%221387-3547%2C%201573-1464%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Flink.springer.com%5C%2F10.1007%5C%2Fs10530-012-0354-2%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-03-24T13%3A19%3A08Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22I7AINDKS%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Scanferla%20and%20Smith%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222020-03-13%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EScanferla%2C%20A.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Smith%2C%20K.%20T.%20%282020%29.%20Exquisitely%20Preserved%20Fossil%20Snakes%20of%20Messel%3A%20Insight%20into%20the%20Evolution%2C%20Biogeography%2C%20Habitat%20Preferences%20and%20Sensory%20Ecology%20of%20Early%20Boas.%20%3Ci%3EDiversity%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E12%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%283%29%2C%20100.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.3390%5C%2Fd12030100%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.3390%5C%2Fd12030100%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Exquisitely%20Preserved%20Fossil%20Snakes%20of%20Messel%3A%20Insight%20into%20the%20Evolution%2C%20Biogeography%2C%20Habitat%20Preferences%20and%20Sensory%20Ecology%20of%20Early%20Boas%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Agust%5Cu00edn%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Scanferla%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Krister%20T.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Smith%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Our%20knowledge%20of%20early%20evolution%20of%20snakes%20is%20improving%2C%20but%20all%20that%20we%20can%20infer%20about%20the%20evolution%20of%20modern%20clades%20of%20snakes%20such%20as%20boas%20%28Booidea%29%20is%20still%20based%20on%20isolated%20bones.%20Here%2C%20we%20resolve%20the%20phylogenetic%20relationships%20of%20Eoconstrictor%20%5Cufb01scheri%20comb.%20nov.%20and%20other%20booids%20from%20the%20early-middle%20Eocene%20of%20Messel%20%28Germany%29%2C%20the%20best-known%20fossil%20snake%20assemblage%20yet%20discovered.%20Our%20combined%20analyses%20demonstrate%20an%20a%5Cufb03nity%20of%20Eoconstrictor%20with%20Neotropical%20boas%2C%20thus%20entailing%20a%20South%20America-to-Europe%20dispersal%20event.%20Other%20booid%20species%20from%20Messel%20are%20related%20to%20di%5Cufb00erent%20New%20World%20clades%2C%20reinforcing%20the%20cosmopolitan%20nature%20of%20the%20Messel%20booid%20fauna.%20Our%20analyses%20indicate%20that%20Eoconstrictor%20was%20a%20terrestrial%2C%20medium-%20to%20large-bodied%20snake%20that%20bore%20labial%20pit%20organs%20in%20the%20upper%20jaw%2C%20the%20earliest%20evidence%20that%20the%20visual%20system%20in%20snakes%20incorporated%20the%20infrared%20spectrum.%20Evaluation%20of%20the%20known%20palaeobiology%20of%20Eoconstrictor%20provides%20no%20evidence%20that%20pit%20organs%20played%20a%20role%20in%20the%20predator%5Cu2013prey%20relations%20of%20this%20stem%20boid.%20At%20the%20same%20time%2C%20the%20morphological%20diversity%20of%20Messel%20booids%20re%5Cufb02ects%20the%20occupation%20of%20several%20terrestrial%20macrohabitats%2C%20and%20even%20in%20the%20earliest%20booid%20community%20the%20relation%20between%20pit%20organs%20and%20body%20size%20is%20similar%20to%20that%20seen%20in%20booids%20today.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222020-03-13%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.3390%5C%2Fd12030100%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%221424-2818%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.mdpi.com%5C%2F1424-2818%5C%2F12%5C%2F3%5C%2F100%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-09-24T21%3A06%3A40Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22QLMRP7YB%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Smith%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221943%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A2%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3ESmith%2C%20H.%20M.%20%281943%29.%20Summary%20of%20the%20collections%20of%20snakes%20and%20crocodilians%20made%20in%20Mexico%20under%20the%20Walter%20Rathbone%20Bacon%20Traveling%20Scholarship.%20%3Ci%3EProceedings%20of%20the%20United%20States%20National%20Museum.%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E93%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20393%26%23x2013%3B504.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.5479%5C%2Fsi.00963801.93-3169.393%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.5479%5C%2Fsi.00963801.93-3169.393%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Summary%20of%20the%20collections%20of%20snakes%20and%20crocodilians%20made%20in%20Mexico%20under%20the%20Walter%20Rathbone%20Bacon%20Traveling%20Scholarship%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Hobart%20M.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Smith%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221943%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.5479%5C%2Fsi.00963801.93-3169.393%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220096-3801%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.biodiversitylibrary.org%5C%2Fpart%5C%2F20473%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-11-10T14%3A17%3A55Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22T4WFLTGY%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Steadman%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221984-07-01%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3ESteadman%2C%20D.%20W.%2C%20Pregill%2C%20G.%20K.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Olson%2C%20S.%20L.%20%281984%29.%20Fossil%20vertebrates%20from%20Antigua%2C%20Lesser%20Antilles%3A%20Evidence%20for%20late%20Holocene%20human-caused%20extinctions%20in%20the%20West%20Indies.%20%3Ci%3EProceedings%20of%20the%20National%20Academy%20of%20Sciences%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E81%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2814%29%2C%204448%26%23x2013%3B4451.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1073%5C%2Fpnas.81.14.4448%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1073%5C%2Fpnas.81.14.4448%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Fossil%20vertebrates%20from%20Antigua%2C%20Lesser%20Antilles%3A%20Evidence%20for%20late%20Holocene%20human-caused%20extinctions%20in%20the%20West%20Indies%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22D.%20W.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Steadman%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22G.%20K.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Pregill%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22S.%20L.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Olson%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Vertebrate%20remains%20recovered%20from%20a%20limestone%20fissure%20filling%20on%20Antigua%2C%20Lesser%20Antilles%2C%20are%20associated%20with%20radiocarbon%20dates%20ranging%20from%204300%20to%202500%20yr%20B.P.%2C%20contemporaneous%20with%20the%20earliest%20aboriginal%20human%20occupation%20of%20the%20island.%20Nine%20taxa%20of%20lizards%2C%20snakes%2C%20birds%2C%20bats%2C%20and%20rodents%20%28one-third%20of%20the%20total%20number%20of%20species%20represented%20as%20fossils%29%20are%20either%20completely%20extinct%20or%20have%20never%20been%20recorded%20historically%20from%20Antigua.%20These%20extinctions%20came%20long%20after%20any%20major%20climatic%20changes%20of%20the%20Pleistocene%20and%20are%20best%20attributed%20to%20human-caused%20environmental%20degradation%20in%20the%20past%203500%20yr.%20Such%20unnatural%20influences%20have%20probably%20altered%20patterns%20of%20distribution%20and%20species%20diversity%20throughout%20the%20West%20Indies%2C%20thus%20rendering%20unreliable%20the%20data%20traditionally%20used%20in%20ecological%20and%20biogeographic%20studies%20that%20consider%20only%20the%20historically%20known%20fauna.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221984-07-01%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.1073%5C%2Fpnas.81.14.4448%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220027-8424%2C%201091-6490%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.pnas.org%5C%2Fcgi%5C%2Fdoi%5C%2F10.1073%5C%2Fpnas.81.14.4448%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-09-03T22%3A37%3A45Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22AYUQF2G4%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Vandeventer%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221992%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EVandeventer%2C%20T.%20L.%20%281992%29.%20%3Ci%3EIn%20search%20of%20the%20Tete%26%23x2019%3Bchien%3A%20Observations%20on%20the%20natural%20history%20of%20Boa%20constrictor%20nebulosus.%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%203.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22conferencePaper%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22In%20search%20of%20the%20Tete%27chien%3A%20Observations%20on%20the%20natural%20history%20of%20Boa%20constrictor%20nebulosus.%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Terry%20L%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Vandeventer%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221992%22%2C%22proceedingsTitle%22%3A%22%22%2C%22conferenceName%22%3A%2216th%20International%20Herpetological%20Symposium%20on%20Captive%20Propagation%20and%20Husbandry%20Uned.%20Proc.%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-08-04T20%3A37%3A02Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22V6QGWM7Z%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Wallace%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221880%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EWallace%2C%20A.%20R.%20%281880%29.%20%3Ci%3EIsland%20Life%20or%20The%20phenomena%20and%20causes%20of%20insular%20faunas%20and%20floras%2C%20including%20a%20revision%20and%20attempted%20solution%20of%20the%20problem%20of%20geological%20climates%3C%5C%2Fi%3E.%20Macmillan%20and%20Co.%3B%20%5C%2Fz-wcorg%5C%2F.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Island%20Life%20or%20The%20phenomena%20and%20causes%20of%20insular%20faunas%20and%20floras%2C%20including%20a%20revision%20and%20attempted%20solution%20of%20the%20problem%20of%20geological%20climates%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Alfred%20Russel%2C%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Wallace%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221880%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22English%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-08-20T12%3A26%3A55Z%22%7D%7D%5D%7D Albino, A. M. (1993). Snakes from the Paleocene and Eocene of Patagonia (Argentina): Paleoecology and coevolution with mammals.

Historical Biology ,

7 (1), 51–69.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10292389309380443 Albino, A. M., & Carlini, A. A. (2008). First Record of Boa Constrictor (Serpentes, Boidae) in the Quaternary of South America.

Journal of Herpetology ,

42 (1), 82–88.

https://doi.org/10.1670/07-124R1.1 Bochaton, C., & Bailon, S. (2018). A new fossil species of

Boa Linnaeus, 1758 (Squamata, Boidae), from the Pleistocene of Marie-Galante Island (French West Indies).

Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology ,

38 (3), e1462829.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2018.1462829 Bonny, K. (2007). Die Gattung Boa: Taxonomie und Fortpflanzung . Kirschner & Seufer.

Breuil, M. (2009). The terrestrial herpetofauna of Martinique: Past, present, future.

Applied Herpetology ,

6 (2), 123–149.

https://doi.org/10.1163/157075408X386114 Bushar, L. M., Reynolds, R. G., Tucker, S., Pace, L. C., Lutterschmidt, W. I., Odum, R. A., & Reinert, H. K. (2015). Genetic Characterization of an Invasive

Boa constrictor Population on the Caribbean Island of Aruba.

Journal of Herpetology ,

49 (4), 602–610.

https://doi.org/10.1670/14-059 Card DC, Schield DR, Adams RH, Corbin AB, Perry BW, Andrew AL, Pasquesi GI, Smith EN, Jezkova T, Boback SM, Booth W, & Castoe TA. (2016). Phylogeographic and population genetic analyses reveal multiple species of Boa and independent origins of insular dwarfism. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution , 102 , 104–116. /z-wcorg/.

Daltry, J. C. (2007). An introduction to the herpetofauna of Antigua, Barbuda and Redonda, with some conservation recommendations. APPLIED HERPETOLOGY , 4 (2), 97–130.

de Lima, L. C. B. (2017). Filogenia e delimitação de espécies no complexo Boa constrictor (Serpentes, Boidae) utilizando marcadores moleculares [Doutorado em Biologia, Universidade de São Paulo]. https://doi.org/10.11606/T.41.2017.tde-26052017-112144

Golden, I. (2017). Origin of the Invasive Boa Constrictor population in St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands. Proceedings of The National Conferences On Undergraduate Research , 864–869.

Gray, J. E. (1825). A Synopsis of the genera of Reptiles and Amphibia, with a description of some new species.

Annals of Philosophy. ,

n.s. v. 10 (1825) , 193–217.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/part/218438 Hynková, I., Starostová, Z., & Frynta, D. (2009). Mitochondrial DNA Variation Reveals Recent Evolutionary History of Main

Boa constrictor Clades.

Zoological Science ,

26 (9), 623–631.

https://doi.org/10.2108/zsj.26.623 Labat, J.-B. (1717). Voyage du Père Labat, aux isles de l’Amérique contenant: une exacte description de toutes ces isles; des arbres, plantes, fleurs et fruits qu’elles produisent; des animaux, oiseaux, reptiles et poissons qu’on y trouve; des habitants, de leurs moeurs et coutûmes, des manufactures et du commerce qu’on y fait etc. P. Lusson et al.

Meerwarth, H. (1901). Die westindischen Reptilien und Batrachier des naturhistorischen Museums in Hamburg. Mittheilungen Des Naturhistorischen Museums Hamburg , 18 , 1–41.

Onary-Alves, S. Y., Hsiou, A. S., & Rincón, A. D. (2017). The northernmost South American fossil record of

Boa constrictor (Boidae, Boinae) from the Plio–Pleistocene of El Breal de Orocual (Venezuela).

Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology ,

41 (1), 61–68.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03115518.2016.1180031 Pyron, R. A., Reynolds, R. G., & Burbrink, F. T. (2014). A Taxonomic Revision of Boas (Serpentes: Boidae).

Zootaxa ,

3846 (2), 249.

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3846.2.5 Quick, J. S., Reinert, H. K., de Cuba, E. R., & Odum, R. A. (2005). Recent Occurrence and Dietary Habits of Boa constrictor on Aruba, Dutch West Indies.

Journal of Herpetology ,

39 (2), 304–307.

https://doi.org/10.1670/45-04N Reynolds, R. G., Puente-Rolón, A. R., Reed, R. N., & Revell, L. J. (2013). Genetic analysis of a novel invasion of Puerto Rico by an exotic constricting snake.

Biological Invasions ,

15 (5), 953–959.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-012-0354-2 Scanferla, A., & Smith, K. T. (2020). Exquisitely Preserved Fossil Snakes of Messel: Insight into the Evolution, Biogeography, Habitat Preferences and Sensory Ecology of Early Boas.

Diversity ,

12 (3), 100.

https://doi.org/10.3390/d12030100 Smith, H. M. (1943). Summary of the collections of snakes and crocodilians made in Mexico under the Walter Rathbone Bacon Traveling Scholarship.

Proceedings of the United States National Museum. ,

93 , 393–504.

https://doi.org/10.5479/si.00963801.93-3169.393 Steadman, D. W., Pregill, G. K., & Olson, S. L. (1984). Fossil vertebrates from Antigua, Lesser Antilles: Evidence for late Holocene human-caused extinctions in the West Indies.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences ,

81 (14), 4448–4451.

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.81.14.4448 Vandeventer, T. L. (1992). In search of the Tete’chien: Observations on the natural history of Boa constrictor nebulosus. 3.

Wallace, A. R. (1880). Island Life or The phenomena and causes of insular faunas and floras, including a revision and attempted solution of the problem of geological climates . Macmillan and Co.; /z-wcorg/.