Scientific Name Chilabothrus inornatus C. inornatus in Cueva Los Perez, located within the Puerto Rico North Karst Belt, deep within a Forest Reserve. Inside the cave are guano mounds taller than a person and a huge bat colony that supports a very rich biodiversity. Photo Salvador Lugo Described and named by Dr. Johannes Theodor Reinhardt (1816-1882), a Danish zoologist and Curator of Terrestrial Vertebrates at Det Kongelige Naturhistoriske Museum, Copenhagen. Holotype Syntypes: Universitetets Zool. Mus. Kobenhavn (UZM) R.5597-98 and R.55101. Stimson presumes the latter is lost

Type locality Puerto Rico.

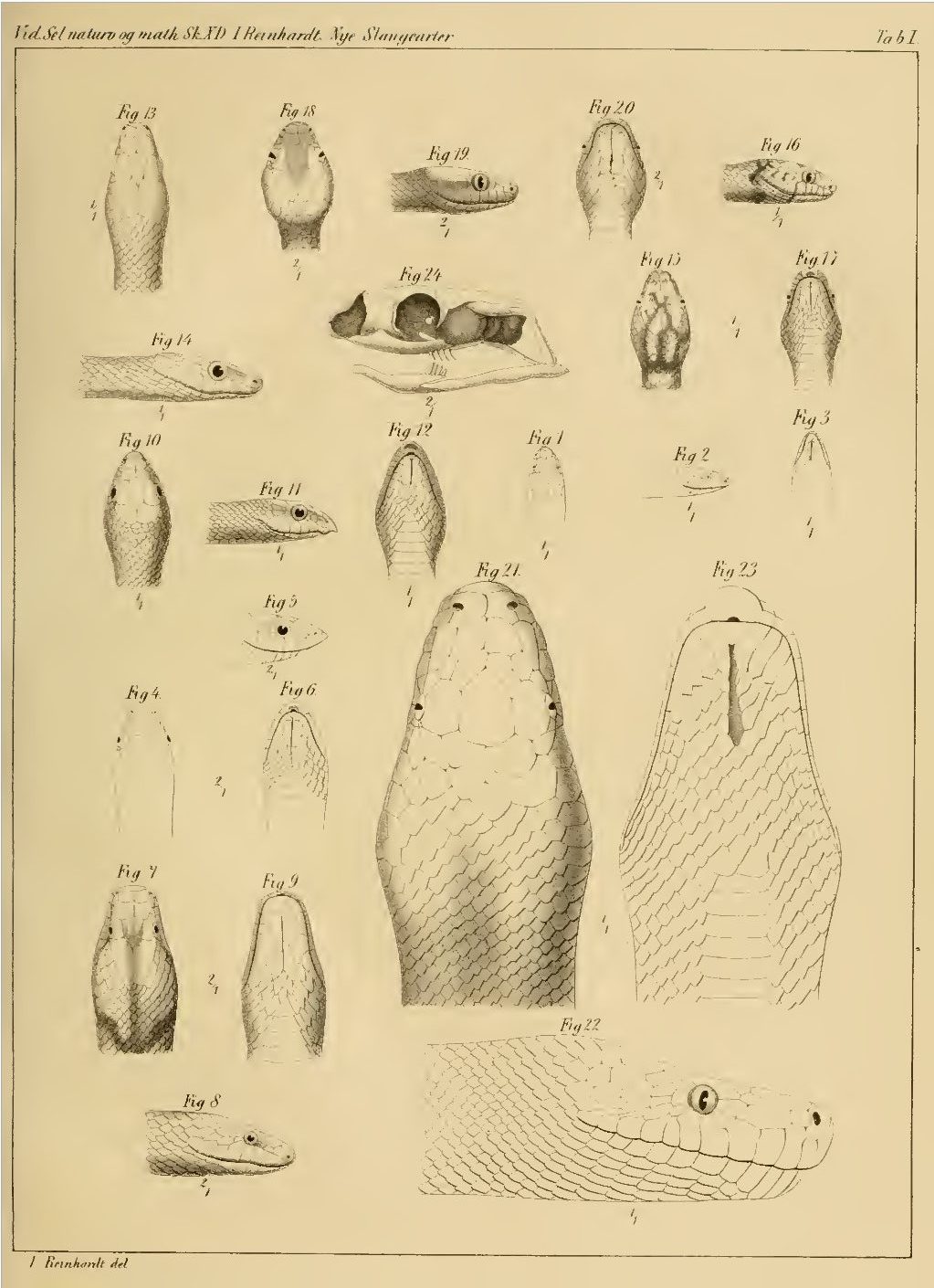

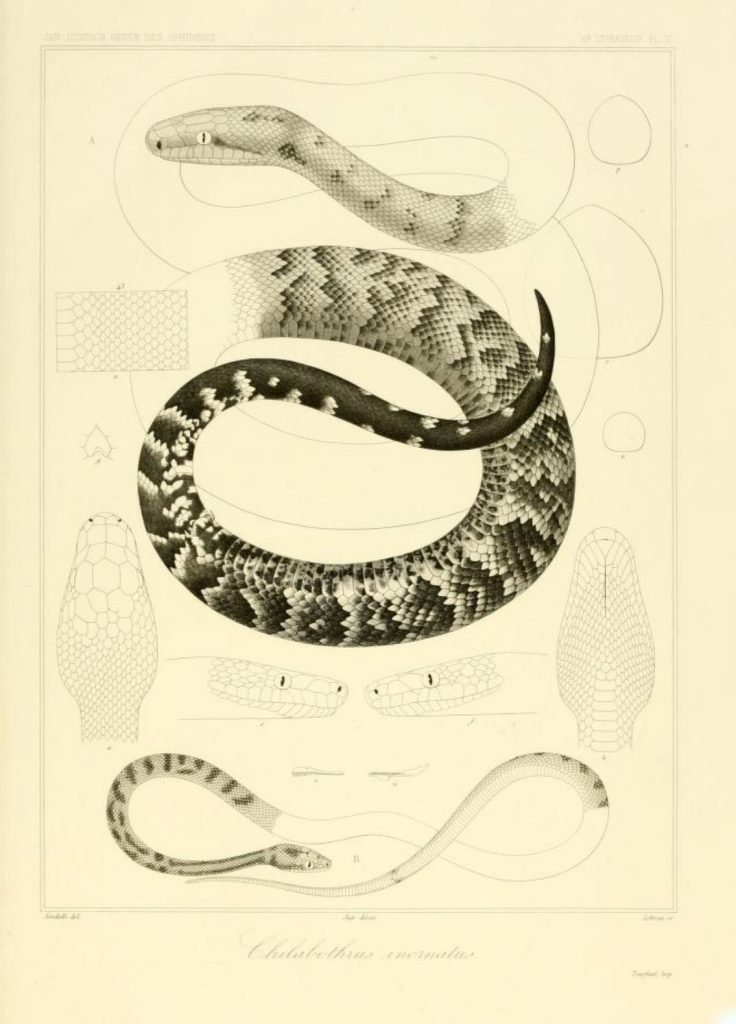

Synonyms Boa inornata 254 ] [255 ] [256 ] [257 ] [fig 21-23 ]Boa inornata Chilabothrus inornatus 564 ] [565 ] [566 ] * Chilabothrus inornatus (Gray, 1849) 104 ]Chilabothrus inornatus Chilabothrus inornatus Chilabothrus inornatus Chilabothrus inornatus Chilabothrus inornatus Piesigaster boettgeri 218 ] [219 ] [220 ] [221 ] [222 ] [223 ] [224 ] [Tab I ] ** [erroneous]Piesigaster boettgeri Front page ] (erroneous)Piesigaster boettgeri ** [erroneous]Chilabothrus inornatus Epicrates inornatus Epicrates inornatus 63 ]Epicrates inornatus 689 ] [690 ] [691 ] [692 ]Epicrates inornatus Epicrates inornatus Epicrates inornatus 131 ] [132 ]Epicrates inornatus Epicrates inornatus Epicrates inornatus Epicrates inornatus 328 ] [329 ] [pl 38 ]Epicrates inornatus 225 ]Epicrates i[nornatus]. inornatus 2 ]Epicrates inornatus inornatus Epicrates inornatus inornatus Epicrates inornatus inornatus Epicrates inornatus inornatus Epicrates inornatus inornatus Epicrates inornatus 96 ] [97 ] [98 ]Epicrates inornatus Epicrates inornatus Epicrates inornatus Rivero, 1978: 101 [102]Epicrates inornatus Epicrates inornatus Epicrates inornatus Boella tenella 20 ] [21 ] [22 ] [23 ] [24 ] [25 ] [26 ] [27 ] [28 ] [erroneous]Epicrates inornatus 163 ] [164 ] [165 ] [166 ] [167 ] [168 ] [169 ] [170 ] [emendation]Epicrates inornatus Epicrates inornatus Epicrates inornatus Epicrates inornatus Epicrates inornatus Tipton, 2005: 45Epicrates inornatus Chilabothrus inornatus Epicrates inornatus Chilabothrus inornatus Chilabothrus inornatus * Chilabothrus is from the Greek meaning cheilos "lip", a "without", and bothros "pits."

* The name inornatus is derived from the Latin for "Unadorned."

** Boulenger (1893) listed P. boettgeri in synonymy. Stejneger (1904) correctly identifies Seoane's specimens as C. inornatus . The specimens were provided to Seoane by his brother, an officer in the Spanish navy. Vanzolini (1977) draws attention to the fact this is Epicrates inornatus , thus making it West Indian.Common name Puerto Rican Boa, Culebron.

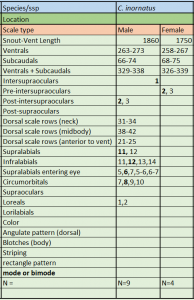

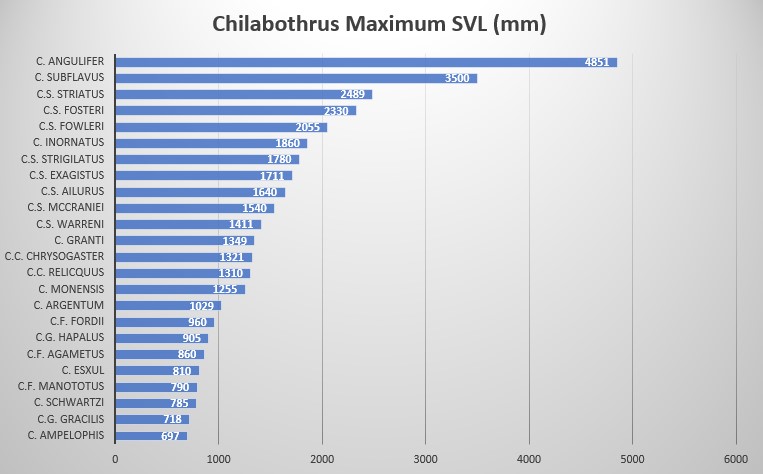

Description and taxonomic notes SVL is to 1860 mm in males, 1750 mm in females; ventrals measure 263-273 in males, 258-267 in females; subcaudals are 66-74 in males, 68-75 in females; ventrals + subcaudals range 329-338 in males, 326-339 in females; intersupraoculars 1 in males and females; pre-intersupraoculars 0 in males, 2-3 (2 modally) in females; post-intersupraoculars 2,3 (2 modally) in males and females; dorsal scales at the neck 31-34 ; dorsal scales at midbody 38-42; dorsal scales anterior to vent 21-25; supralabials 11-12 (11 modally); infralabials 11-14 (12 modally); supralabials entering the eye 5-7 (6 modally); circumorbitals 7-10 (8 modally); loreals 1-2. Neonate SVL is 332 mm-367 mm

Head scales of C. inornatus. Photo Dick Bartlett C. inornatus is a larger boa with light brown/dark brown coloration with a well defined pattern. Some specimens exhibit a grayish coloration. Reddish and yellowish base color specimens have also been reported from small areas (Diaz pers. comm.). The overall coloration is marked with dark brown angulate blotches that may have black outlines. Some specimens are more vividly marked than others. Some specimens may even exhibit little or no markings and appear as dark brown overall, especially as they age.

Wiley observed a large Puerto Rican Boa of 241 cm total length (205 cm SVL) C. inornatus reach lengths of up to 186 cm SVL. Females tend to outgrow males of the same age. Puerto Rican Boas are most closely related to the Mona Boa and the Virgin Island Boa; their lineage split about 10.5 Mya. The next closest relative to the clade is C. angulifer; the lineages split about 15.3 Mya

C. inornatus meristics. * * Source

Boa inornata (figures 21, 22 & 23) Reinhardt, 1843. Distribution Puerto Rico.

With a total area of 8900 km², Puerto Rico is the smallest of the Greater Antilles. It is divided in three physiographic regions or areas of relief: the mountainous interior, the karst region, and the coastal plains and valleys. The island comprises six ecological life zones: subtropical dry forest, subtropical moist forest, subtropical wet forest, subtropical rain forest, lower montane wet forest and lower montane rain forest

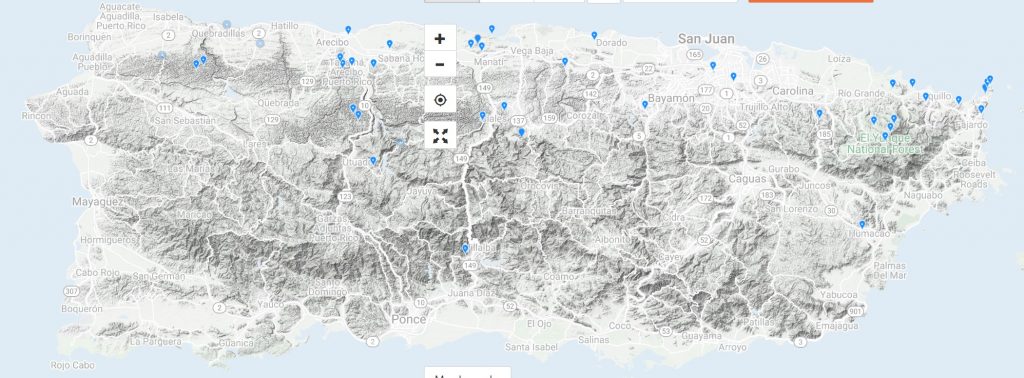

The Puerto Rico Area consists of approximately 200 islands and cays. All these were last connected during the Pleistocene with the lowering of sea levels, leading to a single elongate island that extended from Puerto Rico to Anegada having an area of around 21,000 km2 Chilabothrus inornatus does not occur on the previously connected cays but only on the main island of Puerto Rico

Chilabothrus inornatus by Jan, 1864. C. inornatus is widely distributed throughout Puerto Rico; the US. Fish and Wildlife Service lists its presence for 62 of the 83 municipalities of Puerto Rico

A study listed the Puerto Rican Boa as an introduced species in Florida, based on a single animal that was dispersed with a shipment of garbage from Puerto Rico. This might have been one of very few incidents in which the Puerto Rican Boa was introduced to Florida. Currently there is no evidence of an established population outside its natural habitat

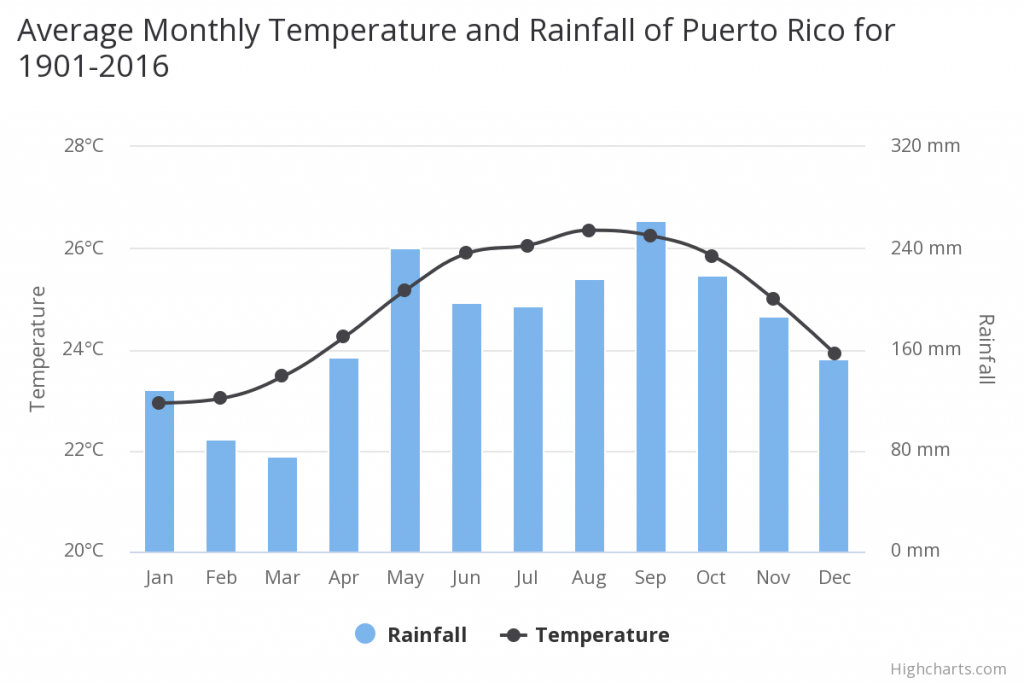

Habitat Puerto Rico’s mean annual temperature is 24.84°C and m ean annual precipitation is 2115.39 mm. Temperatures range from 70 to 90 °F (21 to 32 °C) in the lower elevations, while higher elevations in the central part of the island experience temperatures between 61 and 80 °F (16 and 27 °C) year-round. The forest types that comprise the Puerto Rican landscape are moist coastal forest, moist limestone forest, dry coastal forest, dry limestone forest, lower cordillera forest, upper cordillera forest, lower luquillo forest and upper loquillo forest Ogilby, 1671 ).

C. inornatus resting in a tree. Photo John Jensen. The boa is found in a variety of habitats. It occurs in rain forest, karst landscape, caves (western and central Puerto Rico), dense tropical deciduous forest and altered environments such as plantations and urban areas. Grant states the boas are arboreal and return to the ground on rocky terrain. He reported 2 boas at 700 meters from the headwaters of the Rio Mameyes and on 10 March, 1931 collected a “nice specimen at Piedra Blanca Cliff, at about 1500 feet elevation on the Luquillo Range, near the northeast corner of the island” C. inornatus .

Verified observations of C. inornatus from 2007 to 2020 on iNaturalist.org A radio telemetry study following a small number of boas (n=18) throughout a year found them most often located in live broadleaf trees (52.8%) followed by ground or below ground sites (34.9%). Other sites less frequently occupied included vine enclosed broadleaf trees and shrubs (6.5%); vine tangles (1.7%); sierra palm, Prestoea acuminata (1.0%); tree ferns, Cyathea spp . (0.8%); bamboo, Bambusa vulgaris (0.8%); dead trees (0.7%); stream (0.4%); building (0.3%); and miscellaneous cultivated plants (0.1%)

Several Facebook groups, dedicated to the Caribbean Boas or the Puerto Rico native fauna in general, regularly document the abundance of C. inornatus and the frequent encounters with humans. By all appearances the boa has managed to live in urban and disturbed habitat, with people finding newborn C. inornatus where they live. This is a good indicator of the tenacity of this large boa and its ability to adapt to altered habitats.

Puerto Rico temperature and rainfall data from 1901-2016. Longevity C. inornatus is long lived, reaching at least 28 years of age. J. Wagner is in possession of a Zoo bred female born in 1992, making her 28 years old (Wagner, pers. comm). Murray has 2.2 boas from two Zoos; the boas were born in 1996; making them 24 years old. Despite this advanced age, all the boas are still reproductively active.

Reproduction Slavens reports the following reproduction data:

1979 JACF 0.0.16 born during 1979.OKLO bred during 1980.RHUG 0.0.26 born during 1985.SACC 0.0.11 born during 1985 from a captive breeding.JERE 0.0.33 born during 1986, 13 did not survive.KNOT 6.6.0 born during 1986.JERE 0.0.19 born during 1987.SACC 0.0.9 born Aug 21st.JERE 0.0.14 born during 1988. Two did not survive.JERE 0.0.10 born during 1989. 1 did not survive.SACC 0.0.6 born during 1989.TOLO 0.0.11 born during 1990.ZOOR bred during 1990.JERE 0.0.3 born during 1991.CENC 0.0.6 born 29 Dec 92, 5 did not survive.BALM 0.0.18 born 26 Sep 1996.

Thomas Huff (Canada) found that Puerto Rican Boas mate in March and April

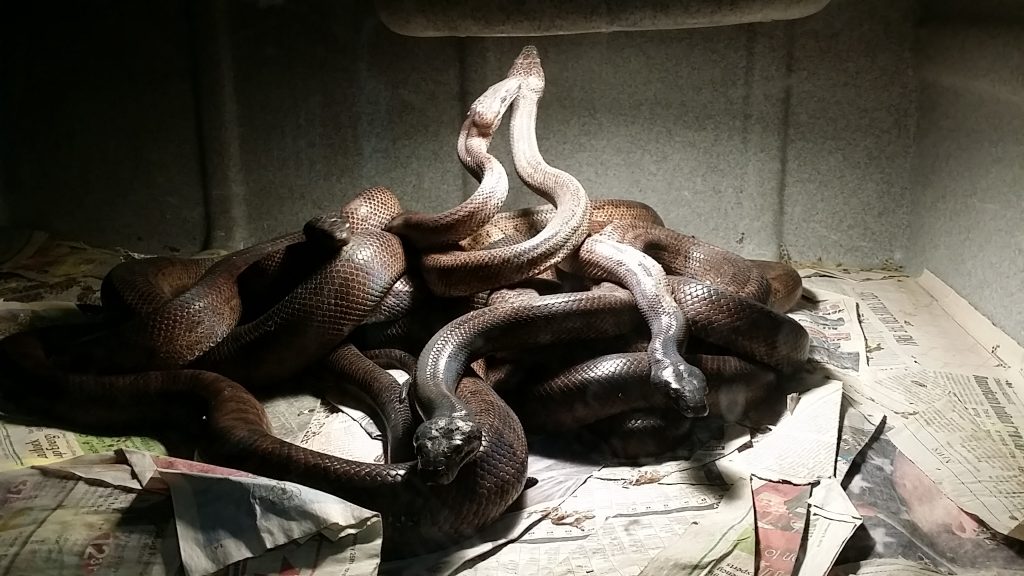

Mating ball of Chilabothrus inornatus, much like that seen in Eunectes breeding behavior. Photo Isaac Laboy. Mating C. inornatus found on a walking path near the entrance to the Arecibo Forest Preserve, Rio Abajo at midday on 29 April, 2022. Photo by Daisy del Valle. Vergner reported two breedings of C. inornatus in Czechoslovakia. The animals mated from May until June and births (both times 12 young) took place in December

Multiple males, though not necessary, are helpful in captive breeding programs to enhance fecundity and litter size. Neither J. Murray nor other recent breeders of the species observed harmful male to male combat during courtship and mating. The males will intertwine their heads and necks and push each other before turning their attention to the female. While one male mates with the female the other males will court her by spurring her back and throwing coils on top of her.

Harmless male to male rivalry during breeding season. In contrast to this, Huff stated that when the males are introduced they react by simultaneously releasing a strong smelling musk and constricting one another.Chilabothrus inornatus has a stereotypical mating behavior with male-male combat, or if the individual behavioral patterns of some animals lead to this observation. In contrast to C. subflavus or C. strigilatus the behavior observed by Huff did not result in (lethal) injuries. Bloxam and Tonge (who received animals from Huff, including 2.2 of the original breeding group) observed male-male combat like Huff did before them

Several Gravid C. inornatus basking during mating season. Wiley observed several gravid females in his study, four of which were smaller than the minimum breeding size (160 cm SVL) reported by Huff. The smallest female containing embryos in this study measured 108 cm SVL and had a mass of 685 g. The gravid boas observed by Wiley contained 13-30 embryos, in addition he reports the largest litter (observed by F. Valentín Rodríguez), which consisted of 37 young. This is the maximum observed litter size for C. inornatus

Most records of active boas in the Luquillo Mountains have been made between March and June, and none have been made between October and December. Peak activity seems to be during periods of rain immediately following prolonged dry spells. This period of maximum activity is at the time when seasonal temperatures, day length, and rainfall levels are increasing

Newborn Puerto Rico Boas, C. inornatus. Behavior Relatively few data exists on behavior in the wild. A telemetry study on 18 animals revealed activity patterns and found an increase in male boa movements from April through June. The researchers believe that males actively search for females at this time. The female movements peaked in July following the male peak, potentially due to increased foraging to sustain embryo growth as well as a shift to environments appropriate for gestation and parturition. The researchers note that the April to July peak in boa movements also approximately corresponded to the period of reproductive activity in some boa prey at the research site

Defensive posture in a juvenile Chilabothrus inornatus. In captivity the young will strike and, with open mouth, swing their head and neck left and right until they come in contact with the offered food item. They eventually grow out of this innate behavior once they become accustomed to their enclosure and feed regimen. Unless C. inornatus is handled from a young age, and quite often, they tend to remain irritable and unpredictable. The boa will often tolerate the keeper’s presence for a very short time and then suddenly lunge in the direction of the keeper. The boas have an exceptional reach when striking.

A case of cannibalism was reported, where a ca. 100-150 cm TL animal constricting and preying upon a conspecific juvenile (ca. 50 cm TL) in a karst valley in Sabana Seca Rodriguez-Duran, first is the piracy of food (a bat). The author reports that the snakes didn’t bite one another, and the fight consisted of pulling different ends of the bat and tangling their bodies. The second observation relates to the timing of boas. The snakes began arriving at the cave several minutes before the bat exodus to over 30 min after the onset of bat activity

While adult boas have been reported as having few natural predators

Diet Adults are opportunist feeders and take rats, mice, birds (including chickens) Erophylla sezekorni lying on the ground. One of these observations involved a stiff, dried bat. Rattus rattus ) were the most common prey item (61.8%). The author also made the observation of a boa preying on one egg and one hatchling at a cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis ) nest at a cay in Bahía Montalva C. inornatus constricting an Iguana took place at Monte Pirata, Puerto Rico.

Puerto Rican boa constricting an Iguana at Monte Pirata, Cabo Rojo. Photo Alberto Caraballo C. inornatus constricting a brown rat at Fajardo, Puerto Rico. Photo Keishla Alvelo Here is a video link C. inornatus taking a bat.

In captivity the adults take a variety of prey items, from chicks to appropriately sized rats and mice. The young take anoles as a first food, with the rare baby starting out on hot pink or fuzzy mice as a first meal. The young take anolis lizards and arboreal tree frogs in captivity

Captive management and population in captivity C. inornatus has become quite popular in captive collections in both the US and Europe. They are readily available every year as a result of captive breeding programs by people with special interest in the West Indian Boas. C. inornatus do very well in captivity and readily breed, producing litters every other year. The Puerto Rican Boa is well represented in collections in the US and the EU.

A genetic diversity study of US C. inornatus in private collections (and several zoos) was conducted by the Department of Biology, UNC in 2019-2020. The study concluded the boas in American collections exhibited a high genetic diversity relative to wild populations. There are 13 females, as well as a “sizable” number of males, that constitute the majority of the diversity and founder stock of the boas in collections and Zoos. These data demonstrate that ex situ US lineages of C. inornatus are more diverse than expected and that the population retains a higher‐than‐expected number of haplotypes and relatively low signature of loss of heterozygosity Invisible Ark .

Conservation status, threats and population size in nature CITES: Appendix II

U.S.A. joined CITES on 14 January, 1974; entry into force on 1 July, 1975.

IUCN RED List: Least Concern (LC) (click here )

Catalogue of Life: (click here)

The National Center for Biotechnology Information: (click here )

CITES import/export data: (click here )

USFWS status: 1 (click here ) 2 (Click here )

Federal Register: (click here )

C. inornatus is protected by the Endangered Species Act of 1973. A recovery plan was put in place in 1983. The species’ status was changed to Vulnerable (VU) in 2004 by the Department of Natural and Environmental Resources, yet it is still considered Endangered (EN) by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The Puerto Rican Boa has never had a Species Survival Plan (SSP), unlike the Jamaican Boa.

The Island of Puerto Rico is the smallest island of the four greater Antilles, having a land surface area of approximately 8,900 km2 . Three main geomorphologic areas are present; the central interior mountain region, the discontinuous coastal plains, and the karst region of the northwest and north-central land areas. At the beginning of the 20th century Puerto Rico was almost completely deforested (80%) owing to the political and economic influence of the United States. Puerto Rico was one of the principal suppliers of sugar cane to the US, resulting in the conversion of large parts of the island’s forests to sugar cane production and to a lesser extent tobacco. By the middle of the century, as little as 34 km2 virgin forest remained. When the sugar cane industry collapsed about 70 years ago much of the land devoted to the industry was abandoned. Since then there has been an impressive increase in the amount of forest cover

Puerto Rico’s history of protecting areas for conservation purposes goes back to 1876, when the Spanish Crown protected areas in El Yunque and Utuado. Laws of the Spanish Crown protected forests, mangroves and water resources. Currently, an important face for the conservation of land and biodiversity on the island is the Puerto Rico Conservation Trust, a private corporation. Since 1970 it has managed to acquire and protect twenty natural areas for conservation for a total of 21,364 acres (86.5 km² )

Conversely, US policies also contributed to the protection and conservation of land and biodiversity mostly in the Luquillo mountains in eastern Puerto Rico

Regarding the use of snake oil, Grant (1933) remarks, “Snake oil is in great demand for “medicinal” purposes, but the fat must be extracted from a living snake. Much hog fat is sold by the reputed snake oil sellers. The hind part of the body of my six foot specimen held about two cups of very soft, fine fat”

Today Puerto Rican Boas might be still killed by humans (even though we are unaware if snake oil is still used) and it is predated on by introduced mongooses. The human alterations on the Puerto Rico landscape are severe and due to an increasing population, this trend will most likely continue. A stronghold for Puerto Rican Boas are inaccessible karst areas, which this species prefers. However the karst areas are considered a vital resource for Puerto Rico and its economical Importance is being recognized (water, minerals, agriculture and forestry)

Much of the boa’s apparent rarity undoubtedly relates to observers’ difficulties in visually detecting the species in forests

The IUCN justified its 2010 rating of LC with the following:

Chilabothrus inornatus is assessed as Least Concern due to its large distribution, lack of widespread threats, and ability to inhabit altered environments. Population numbers have declined in the past but this boa is still relatively common in many areas, and occurs in several protected areas.This abundance in natural and altered habitats was recognized; so much so, a CITES study submitted in 2016 found the boas had made a sufficient recovery and recommended delisting the Puerto Rican Boa from Appendix I and relisting it as Appendix II. The study documents:

i) given the absence of international trade, (ii) given that it is the only endemic boa therefore trade in other similar species is non-existent, and (iii) given its common and widespread occurrence on Puerto Rico, we conclude that the species does not meet the criteria indicated in Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev. CoP16) Criteria for amendment of Appendices I and II and should be moved from CITES Appendix I to II. The USFWS, via the Federal Register seen here , requested comments from interested parties as it considered removing the Puerto Rican Boa from the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife on 13 July, 2022. As of May, 2023 there has been no decision published by the USFWS.

During the recent CITES conference held in Panama City, Panama from 14-25 November, 2022 it was agreed by the Conference of Parties (CoP) the Puerto Rican Boa, Chilabothrus inornatus be downgraded from CITES Appendix I to Appendix II, effective 23 February, 2023. This Notification to the Parties can be found here . We found the USFWS Bulletin somewhat vague regarding the bullet point for Chilabothrus inornatus and sent an email to the agency requesting clarification. The agency’s response (pers comm) read, “The CITES reclassification does not affect the ESA listing in any way. U.S. trade with the species would still need to meet the ESA Import/ Export Requirements. The CITES listing only affects international trade so there are no changes to its interstate movement or sale at this time.”

Despite the fact that Puerto Rico has a long history of protecting areas for conservation purposes, dating back to 1876, when the Spanish Crown protected areas in El Yunque and Utuado, the current situation leaves room for improvement. A study by Castro et al. analyzed a total of 95 protected areas that represent 8.2% of the land surface area. The majority of the protected sites were rather small (often less than 10 km2 ). The protected areas are effective in conserving species because they are located within the most species-rich regions on the island and because they include sites classified as critical wildlife areas or important bird and biodiversity areas. Additionally, they encompass diverse landscapes, are dominated by core forest and include predicted habitats for 31 threatened vertebrate species

The percentage of land surface protected lags behind the UN Millennium Development Goals for 2020, which seek to protect 17% of terrestrial areas and 10 percent of nationally administered marine areas (http://www.cbd.int/sp/targets/). The problem of isolation of the protected areas must not be underestimated, since it could lead to a fragmentation of populations which might in the long term lead to inbreeding due to the lack of exchange of genetic material. Puerto Rican Boas are capable of tolerating human activity in their proximity and might even profit from rodents cohabiting human populated areas. However, this is largely dependent on the type of landscape alteration as well as the pressure placed upon the boas when encountering humans.

The latter point can be addressed by wildlife education; the Puerto Rico Conservation Trust, a private corporation, offers excellent interpretative nature programs at Las Cabezas de San Juan Natural Reserve in Fajardo, Hacienda Buena Vista in Ponce and in La Esperanza en Manatí

The CIA World Factbook lists the following environmental threats for Puerto Rico: soil erosion; occasional droughts cause water shortages; industrial pollution

We predict this boa will be removed from the ESA in the years to come. Through the efforts of the Invisible Ark individuals such as J. Murray, T. Crutchfield, J. Wagner, S. Woodward, R. Stone, etc. this boa is in almost every state in the country. Through gifting and breeding loans this boa has made an amazing recovery and, in the process, has managed to maintain its genetic diversity through responsible breeding. The USFWS has seen fit to make exceptions to the Lacey Act with regard to the CITES I/App I Madagascar Boas (Sanzinia & Acrantophis ) as well as several App I tortoises. Affording the Puerto Rican Boa and Jamaican Boa the same exceptions would allow the free trade of genetics and blood lines across state lines without the ensuing red tape that makes it impossible to do so. This is a very reasonable and scientifically sound recommendation on the part of the authors.

The map below illustrates the extent of habitat destruction and alteration due to development and agriculture.

Puerto Rico Early map of Porto Rico, 1760-1769. On display in these Zoos Several zoos keep Chilabothrus inornatus. For holdings in European and Russian Zoos see here . Unfortunately most non-reptile enthusiast visitors to zoos fail to recognize the beauty of this species. So much that in fact C. inornatus was the second least attractive boid species (surpassed only by C. gracilis ), which negatively affects the holdings of the species in public institutions

Intriguing Inornatus Puerto Rican Boa

Chilabothrus inornatus Note the midbody swelling due to ovulation. Picture by

Jeff Murray

Puerto Rican Boa

Chilabothrus inornatus , Litter of newborn animals. Picture by

Jeff Murray

Puerto Rican Boa

Chilabothrus inornatus , Litter of newborn animals. Picture by

Jeff Murray

Puerto Rican Boa

Chilabothrus inornatus , Female with newborn litter. Picture by

Jeff Murray

Puerto Rican Boa

Chilabothrus inornatus , Litter of newborn animals. Picture by

Jeff Murray

Puerto Rican Boa

Chilabothrus inornatus , Litter of newborn animals. Picture by

Jeff Murray

Puerto Rican Boa

Chilabothrus inornatus , newborn animal, note the size of the animal. Picture by

Jeff Murray

Continue to Chilabothrus monensis Citations

{2129430:Y29CBNZC};{2129430:F9XC9DJD};{2129430:Y29CBNZC};{2129430:ZQTKYERM};{2129430:4M2S3VRG};{2129430:FKN8ZAUB};{2129430:FEDSP6RC};{2129430:8597BW5I};{2129430:SFATR6IH};{2129430:5UR46KHT};{2129430:ZABN4Y4X};{2129430:TCBYKTNZ};{2129430:IFAFZEGF};{2129430:SSWBN5AF};{2129430:HDVKI8LR};{2129430:FTX7PLWT};{2129430:M5C6WETQ};{2129430:FTYCYVBR};{2129430:F9XC9DJD};{2129430:WPYXP4KX};{2129430:GMXVACUY};{2129430:AT8W4WR7};{2129430:MWAJWBEI};{2129430:8JQN59AC};{2129430:6QFFGCRZ};{2129430:JGW4QVFZ};{2129430:8IA8FZ6I};{2129430:QHW3LQDU};{2129430:CWJEARHH};{2129430:6SCYJ9AY};{2129430:ERLBGK22};{2129430:PCLHMKXD};{2129430:TRWL9T99};{2129430:SWS6AK9A};{2129430:AMNVQLZB};{2129430:9N4BJA59};{2129430:ZT45LISV};{2129430:9VXQKNGX};{2129430:WPYXP4KX};{2129430:XK6LXCSK};{2129430:KBUREJ85};{2129430:B53MA79J};{2129430:TW73PF3T};{2129430:8UKJPUTU};{2129430:WPYXP4KX};{2129430:FNLEFGSL};{2129430:DDF8G6AQ};{2129430:SSWBN5AF};{2129430:JWABJ7CX};{2129430:6JWGCZJW};{2129430:GD8RDCVY};{2129430:4I9WRVZJ};{2129430:IFAFZEGF};{2129430:6JWGCZJW};{2129430:NYMR2UTX};{2129430:C3BZJLKM};{2129430:GD8RDCVY};{2129430:C3BZJLKM};{2129430:ZT45LISV};{2129430:4I9WRVZJ};{2129430:6JWGCZJW};{2129430:8UKJPUTU};{2129430:6KSBAKFK};{2129430:4I9WRVZJ};{2129430:ICDYBZ7Y};{2129430:4I9WRVZJ};{2129430:KV73ESVE},{2129430:ZT45LISV};{2129430:GIGKAEN7};{2129430:6KSBAKFK};{2129430:ZT45LISV};{2129430:4I9WRVZJ};{2129430:TWFRDIE4};{2129430:DDF8G6AQ};{2129430:XK6LXCSK};{2129430:Z9GRZV9L};{2129430:3SDZUAWY};{2129430:SSWBN5AF};{2129430:JDHC72NQ};{2129430:QHW3LQDU};{2129430:6JWGCZJW};{2129430:EFF45GC8};{2129430:4I9WRVZJ};{2129430:RFJFN9QV};{2129430:XK6LXCSK};{2129430:XK6LXCSK};{2129430:PJNEUXIK};{2129430:CQY3KLAD};{2129430:AZEJCDPM}

apa

author

asc

no