Scientific Name Boa orophias Photo Sebastian Holch Described and named by Carl Linne (1707-1778). Better known as Linnaeus, he is responsible for inventing the system we use today to name, rank and classify living organisms. Holotype A specimen currently in the Museum de Geer with 280 ventrals is taken to be Linnaeus’ type, fide Andersson (1899).

Type Locality None designated; here restricted to Praslin, Saint Lucia.

Subspecies None.

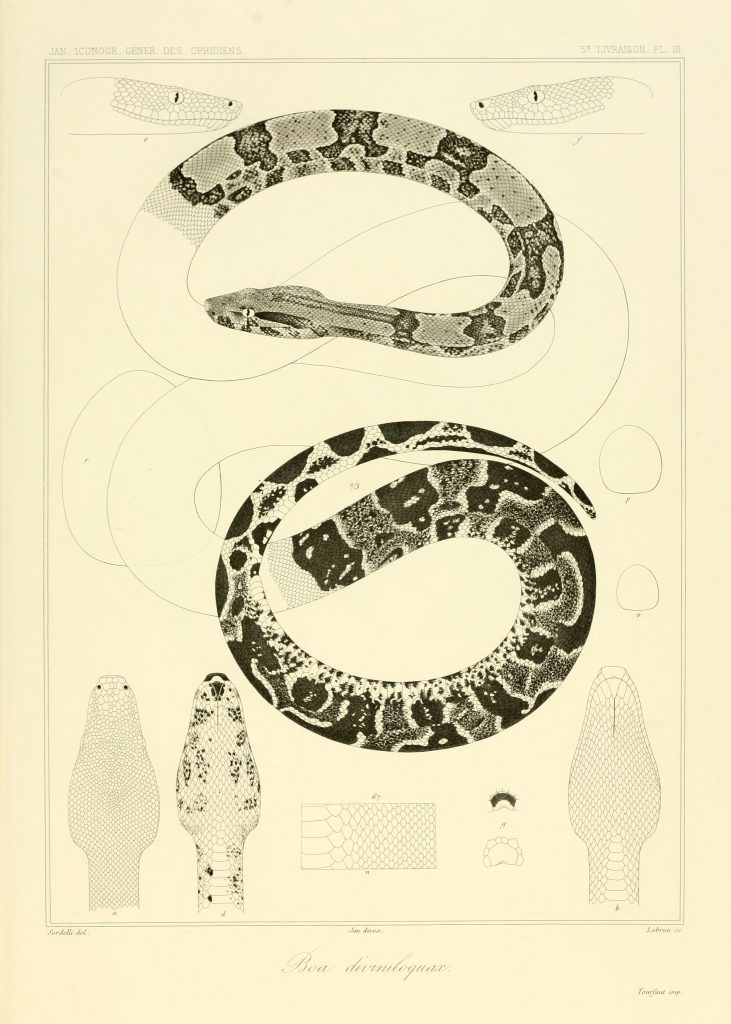

Synonyms Breton, 1665: Dog’s head Du Tertre, 1667:Boa orophias Boa orophias Boa ophrias Constrictor orophias Boa ophrias Boa ophrias Boa ophrias Boa ophrias Boa ophrias Boa ophrias 127 ]Boa ophrias 179 ]Boa ophrias Boa orophias Boa ophrias Boa ophrias Boa ophryas Boa ophrias 129 ]Boa ophrias Boa orophias Boa orophias Constrictor diviniloquus 240 ] [241 ] [242 ]Boa orophryas and Boa ophryas Boa diviniloqua 516 ] [517 ] [518 ] [519 ]Boa diviniloqua 101 ]Boa diviniloqua Boa diviniloquax Boa orophias Boa diviniloquax Boa diviniloquax Jan, 1864: pl. IV Boa diviniloquax var. mexicana Jan, 1864: pl. V Boa diviniloquax 82 ] [80 ]Boa diviniloquax Boa diviniloquax var. mexicana Boa diviniloquax Boa diviniloqua Boa diviniloqua Boa diviniiloqua Boa diviniloqua 102 ] [103 ] [359 ]Boa ophrias Constrictor orophias 185 ]Constrictor orophias 330 ]Boa diviniloqua Boa diviniloquus Constrictor constrictor orophias Constrictor orophias Constrictor orophias Constrictor constrictor orophias 111 ]Constrictor constrictor orophias Constrictor orophias Constrictor constrictor orophias 152 ]Constrictor constrictor orophias 262 ] [263 ] [264 ] [265 ] [268 ] [269 ] [270 ] [272 ]Boa constrictor orophias Boa constrictor orophias Boa constrictor orophias Boa constrictor orophias Boa constrictor orophias Boa constrictor orophias Boa constrictor orophias Boa constrictor orophias Boa constrictor orophias Boa orophias Walls, 1998: 62Boa constrictor orophias Crother, Censky & Kaiser, 1999: 213 [214]Boa constrictor orophias Tipton, 2005: 40Boa orophias Boa constrictor orophia s Boa orophias Boa orophias Boa orophias Boa orophias Boa orophias Boa orophias Lescure et al, 2020: 62 [67] [fig 2]Boa orophias Thorpe & Malhotra, 2023: 1-14Common Name Saint Lucia Boa, Saint Lucian Boa, Tet’chien (french for “Dog Head”).

Taxonomic history Boa orophias. Exceptional painting of Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle specimen no. MNHN-RA-0.1995. By Vaillant, 1851. The earliest mention of Boa orophias comes from Father Du Tertre in 1667 there meets Snakes as in the island of Martinique, but they are not so dangerous. There is a species that is called dog’s head…. They bite more frequently than the others but their venom is not so subtle or so bad as that of the Serpent of Martinique”

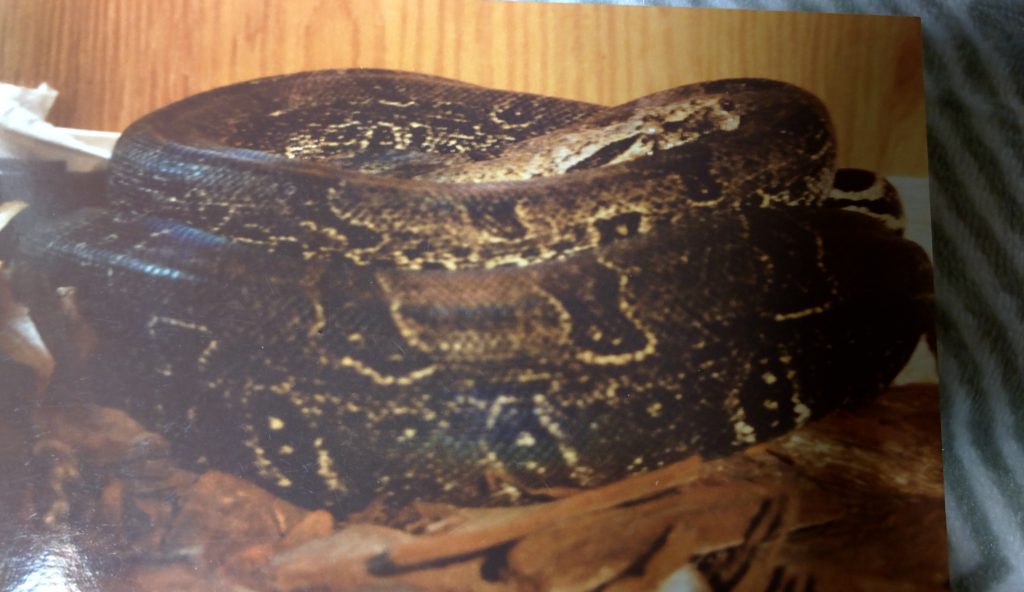

Dumeril remarked, in 1854, “The first, of which the Museum has only had a single copy for a long time, which had been brought back alive from the island of Saint Lucia by Mr. Arthus Fleury, is the Boa diviniloque (Boa diviniloquus). This island of the Antilles seems to be, until now, the almost exclusive homeland of this elegant Ophidian. The magnificent metallic reflections of its integuments, which are adorned with the most beautiful blue or greenish shades, depending on the play of light, explain its vulgar name of Blue Boa. Six subjects of this species have been procured in these last three years by the care of a traveler, M. de Bonnecour, who has stayed in Saint Lucia. They all endured captivity fairly well, for the one who succumbed the most quickly did not die until half a year; two others lived about eighteen months; a third for more than twenty-seven months”

Andersson (1899) wrote, “The authors seem to have been doubtful about the identification of this snake. Schlegel considers it to be a variety of Boa constrictor . Duméril and Bibron reckoned one of Laurenti’s species, Constrictor divinoloquus , though with ?, as a synonym to this; so also does Boulenger. I am now able to prove that Linneaus’s Boa ophrias is the same as the Boa divinoloqua of the authors, which thus ought to be namedBoa ophrias (L.)” (Andersson 1899).

Per Lazell (1964) the oldest available name for a Lesser Antillean form is Boa orophias (Linnaeus, 1758). The ventral count provided without doubt assigns the name to the Saint Lucian boa since no other boa in the genus has 281 ventral scales. The name diviniloqua, used by Dumeril & Bibron (1844) was originally assigned by Laurenti in 1768. Lazell then reasons diviniloqua , sensu Dumeril & Bibron, is a junior synonym of orophias. Diviniloquus, sensu Laurenti does not apply to any other Lesser Antillean boa. Of the two boas, Saint Lucia and Dominica forms, it could only apply to orophias . The few specimens in collections, both Dominica and Saint Lucia forms, have always been referred to as orophias . In 1935 Stull combined the Saint Lucia and Dominica forms under orophias and differentiated them at the species level (constrictor orophias ). Lazell stopped short of assigning the boa full species status; he used the stepped-cline series and determined the boa to be the middle member of three steps

Price and Russo in their description of Boa constrictor longicauda recommended, without justification, the Saint Lucia Boa be elevated to full species

Description and taxonomic notes Dorsal scale rows at mid-body 65-75, ventral scales 270-288. Dark brown cross bands dorsally, generally broken from the lateral blotches, giving the appearance of being offset from each other. Dark subrectangular dorsal saddles numbering 27-31 to vent. Rich brown ventral coloration turning to white from vent to tail tip. White coloration with black or gray spotting. Distinct and complete subocular stripe; loreal is largely obsolete; infralabials and chin pigment do not correspond to the facial stripes. Convex canthus with a prominent snout

The exquisite head markings of the Saint Lucia Boa. Photo Edward Bell Lazell pointed out that several morphological characters differ in Boa orophias compared to Boa constrictor. These are scale size increased compared to Boa constrictor (resulting in decrease in dorsal scale rows at midbody), number of transverse saddles, darkness of coloration, irregularity of pattern, obliteraion of facial markings and convexity of the canthus, highest average number of ventral scales. Lazell hypothesized the evolutionary relationships of the Lesser Antillean Boa species and came to conclude that they were a result from a northward moving of the species. He termed this stepped-cline series displaying geographic variation

Boa orophias in situ, Anse La Raye. Photo Ashton Smith Distribution Saint Lucia.

Brown and several other authors, name the distribution St. Kitts Bothrops caribbaeus . Surprisingly, Lazell could not confirm a cohabitation of the two species

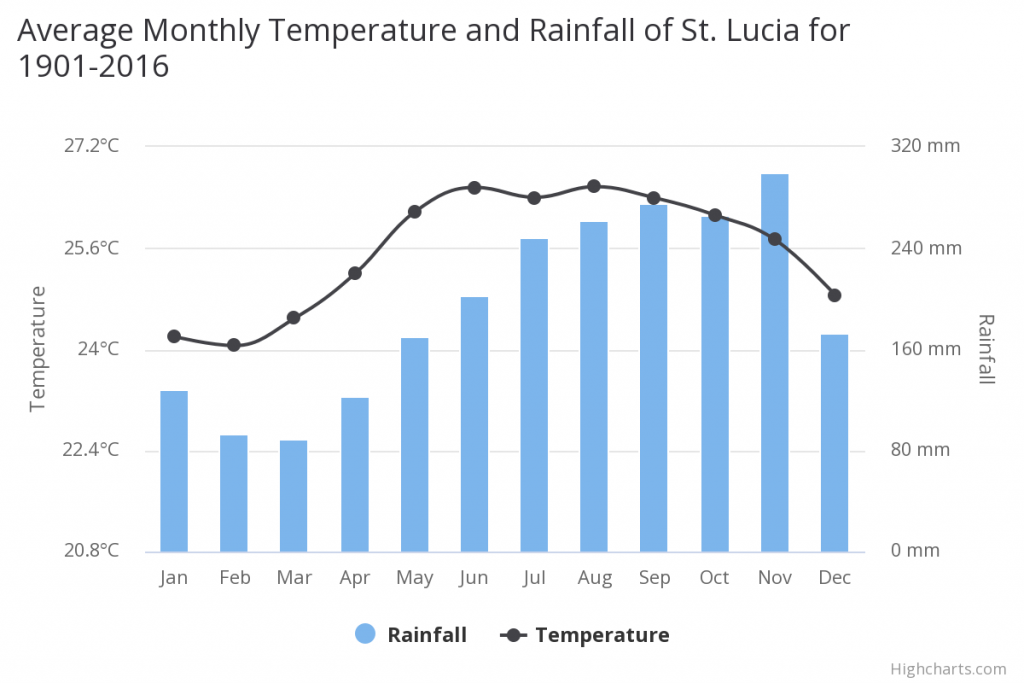

Habitat On Saint Lucia the mean annual temperature is 25.56°C and the m ean annual precipitation is 2330.05 mm. Rainfall differs across the island with about 1500 mm in the north and south ends and around 3700 mm at Edmund and Quiles in the south-central mountainous area. Saint Lucia has a tropical maritime climate throughout the year with some relief from the high temperatures and humidity being offered by the easterly (trade) winds that blow from the northeast. Although it rains during every month of the year, there is a well-defined rainy or wet season that occurs between June and November. Precipitation during the wet season comes mainly from tropical waves, depressions, storms and hurricanes, which occur frequently over this region owing to its geographical location within the Atlantic hurricane belt. The tropical cyclone season typically lasts from late June until October, with severe tropical storms in November. The drier months are from January to May

The town of Castries, St Lucia. Fielding, 1837. Saint Lucia is a volcanic mountainous island with a total land area of 616 km2. Its coastline measures 158 km, with the capital town Castries, located in a bay on the northwest coast of the island. The island’s topography consists of a narrow coastal ridge with deep valleys and rugged mountains in the central region. Its lowest point is at the Caribbean Sea (sea level) and the highest point on the island, Mount Gimie of the south-central mountain clusters, reaches 950 meters. Forest composition on the island consists of scrub forest, open woodland, grassland, rain forest, montane thicket, mangrove, secondary natural forest, elfin woodland and plantation forest

Boa orophias habitat in Anse la Raye. Photo Ashton Smith Boa orophias in the wild. Photo Bobby Neal Gravid Boa orophias at about 500 meters elevation on Saint Lucia. Photo Chris Smith Since the distributions of Bothrops caribbaea and Boa orophias are largely coastal and overlap completely, with B. orophias ranging to slightly higher elevations (around 350 meters) it was suggested that this might be an indication of a “relatively recent colonization combined with a slow spread through the inhabited areas that provide sufficient rodent abundance”

Habitat of Boa orophias in Anse la Raye. This is in the hills where streams empty into this reservoir. Photo Ashton Smith During a DNA collection trip to Saint Lucia in 2003, Peter Taylor (pers. comm.) writes, “We were allowed to enter and do our research with the permission of the St. Lucia Forestry Dept. Even the St. Lucia public is not allowed into this protected area without accompaniment…the mile long reservoir is a public water supply. The southern end feeder streams margins draining into the reservoir serve as excellent habitat for vipers and boas as the natural openings in the forest they create allow sunlight to reach ground level. A lot of the snakes we encountered of the both species were females. We suspect the stream edges provide gestative basking areas for snakes in reproductive condition. The steams are very rocky and bolder strewn, the rocks getting larger and larger the further in you go to the point of a mile or less before the terrain and obstacles make the situation impenetrable”.

He continues, “That area contains some of the healthiest and least disturbed habitat on the island and is where the high profile endangered St. Lucia Amazon parrot has its strongest remaining populations”.

Boa orophias on Saint Lucia. Photo Ashton Smith. In 2003 a DNA collection trip was conducted on Saint Lucia for Boa orophias and the endemic species of Bothrops . A link to the video entitled, “St. Lucia Boa DNA sampling in the wild “, is here .

Donald Anthony of the St. Lucia Forestry Department. Tyler reported that this snake was found in great numbers in (sugar) cane-pieces Boa orophias was found in a cavity of an acomat boucan tree 7.22 meters off the ground

Boa orophias in its habitat. Photo Ray Thompson

Boa diviniloquax by Jan, 1864 In comparison with Boa constrictor, Boa orophias is more slender. It might also be smaller as the largest specimens collected by Lazell measured 2.365 m, a male collected from Anse La Raye (MCZ 75847) and 2.305 m (a female collected from Praslin (MCZ 75848). However, Lazell mentioned that he observed a considerably larger Boa orophias at Anse-La-Raye, but had no intention of collecting it

Bonny describes a 10 year old captive bred female in his possession with a length of 2.44 m and a mass of 8.4 kg. He notes that typically Boa constrictor of the same length have at least 30-40% more mass than Boa orophias Boa orophias has been isolated for at least 2 million years and that the potential for gene flow between the islands is virtually nil

Longevity We assume Boa orophias can live equally as long as its congeners.

Several Boa orophias males courting a female in situ. Photo Roger Thorpe Reproduction Much of the reproduction knowledge we have stems from captive breedings. These found that litter sizes were smaller and that mating season starts in mid-end of December and lasts until mid March (T. Wilkins, J. Murray, see below) and Boa orophias gave birth to 23 young in July

A pair of Boa orophias mating. Boa orophias mating with an ambient temp of 62°F-64°F. Behavior

B. orophias were referred to as “large tree snakes” by Barbour

Diet Bat predation Boa orophias (weight 396.9 g, total length 110 cm), was observed in the trunk of an acomat boucan tree feeding on a gravid Brachyphylla cavernarum (67g). Unlike either the Cuban or the Puerto Rican boas, which were observed capturing bats in flight, the St. Lucia boa was observed preying upon resting individuals

Captive management and captive population Adult Boa orophias are well behaved and hardy captives. T. Wilkins bred Boa orophias five times (pers. comm.), J. Murray bred the adults twice (1996 & 1998), Chad Brown bred his adults once. Litter sizes were relatively small compared to most species of Boa constrictor – mean litter size consisted of 8 babies. All J. Murray and C. Brown stock came from offspring produced by T. Wilkins.

Gravid Boa orophias. The babies are born laterally compressed compared to all other species in the genus Boa. Captive bred young are especially nervous and will hiss and/or strike at the first sign of movement on the keeper’s part. This is to the detriment of all feeding attempts as the youngsters are too focused on the keeper and ignore all offered food. Defrosted fuzzy mice were left in overnight; the rodents were placed at the entrance to the hide, with the entrance to the hide facing the back of the tub. This minimized any contact with the babies and was helpful in getting them to feed. Boa orophias was also bred by several European private breeders (K. Bonny) from the 1980’s to the early 2000’s.

Gravid Saint Lucia Boa. Today this species is a very rare sight in private collections and we are unaware of any recent successful breedings. We feel this boa is a good candidate for legal export from the Island and placed in ex situ breeding programs undertaken by responsible institutions and collectors in the private sector. This boa is a prime candidate for the Invisible Ark .

Boa orophias. It is suspected this boa rafted to Antigua. It was found on Horsford Hill on 19 December, 2019. Photo Michael Drew Elderly St. Lucia boa (Boa orophias) from Bob Sears. Conservation, threats and population size in the wild CITES: Appendix II

IUCN Red List: Endangered (EN)

Catologue of Life: (click here )

The National Center for Biotechnology Information: (click here )

CITES import/export data: (click here )

The IUCN provided the following for their 20 July, 2015 rating of EN:

Listed as Endangered on the basis that this species has an extent of occurrence of 270 km2 and area of occupancy calculated as 48 km2 , and occurs at fewer than five locations defined by varied threats mainly from habitat loss and persecution. A population decline has been reported and is ongoing, and while this does not appear to be at a rate approaching 30% over three generations there is a continuing decline in the number of individuals, as well as in the extent and quality of its habitat and, once planned development is underway, it will certainly undergo a decline in its area of occupancy and number of locations. Tyler wrote that the Boa was welcomed in the sugar cane fields because it preys on rats, however, the natives seem to have feared the snake to a great deal, so much that “few natives can be induced to touch or even approach very near to it ” Bothrops caribbaeus

Boa orophias on Saint Lucia. Photo Edward Bell Corke investigated the conservation needs for the terrestrial herpetofauna of the different Windward Islands. He did not put a larger focus on the Boa fauna as he states that Boas remain relatively frequently reported on all the islands to which they are native

Boa orophias killed and being prepared for a meal. Photo The Loop Recently there has been a spate of killing and eating or mistreating the endemic boa. It is featured in the local online paper here

A technical report from 2009 lists the wildlife use in saint Lucia. The report states that: The boa is being used for at least two uses: as a tourist attraction (or sometimes to attract Saint Lucians) and to produce snake oil. Snake oil is apparently especially valued, and valuable, in the French territories (Martinique, Guadeloupe) and may be exported to them. Local producers may also produce snake oil for friends/relatives (e.g. on request) rather than for sale. The Forestry Department do issue a small number of licences to collect boas

In line with the snake oil use stated in the report from 2009 is what Jenny Daltry communicated to us. Ms. Daltry is working with the re:wild and Fauna & Flora International organizations as Caribbean Alliance Director. She told us that she has heard anecdotal reports, of boas being harvested for their fat and trafficked to Martinique. While hard/quantitative evidence is lacking, the Head of the Wildlife Unit (Saint Lucia Forestry Department) recently told her that a live boa was found at the regional airport near Castries, which he inferred to have escaped while being trafficked.

The phenomenon of snake oil usage might pose a threat yet not fully accounted for or understood. Ms. Dalrty told us that she recently photographed snake oil for sale also at a tourist craft shop in Dominica, which indicates that both endemic Boa species are affected by this (J. Daltry in litt. March 2024 )

The CIA World Factbook lists the following environmental threats for Saint Lucia: deforestation; soil erosion, particularly in the northern region

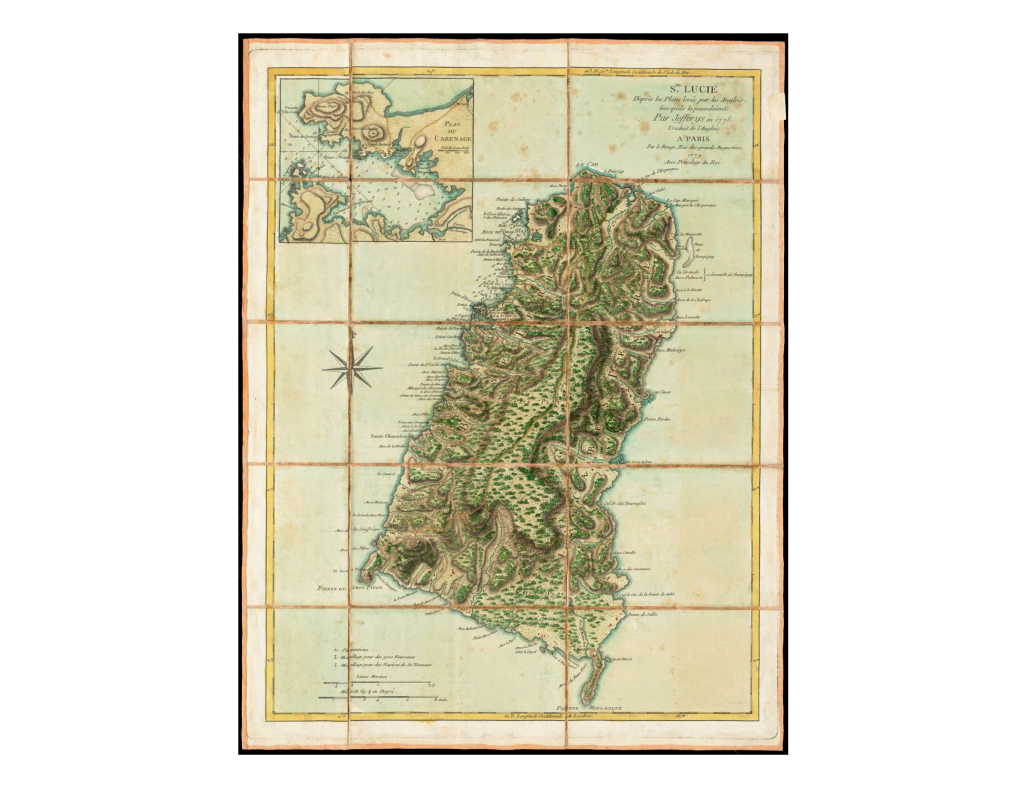

The map below illustrates the extent of habitat destruction and alteration as a result of development and agriculture on the island.

Saint Lucia Early map of Saint Lucia, 1779. On display in these Zoos Boa orophias is not maintained in any zoo worldwide, that we are aware of.

Luring Lucians Gravid Saint Lucia Boa. Photo by Jeff Murray

Gravid Saint Lucia Boa. Photo by Jeff Murray

Links to further photographs Boa orophias from Anse la Raye

Boa orophias from Anse la Raye

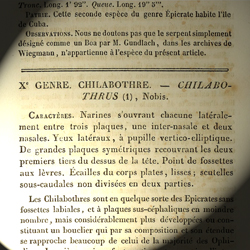

Continue to Genus Chilabothrus Citations

{2129430:4YKJF6UR};{2129430:U4X2CEG2};{2129430:6C2G3SEZ};{2129430:CG39XSAA};{2129430:B5KXQKJ6};{2129430:FKN8ZAUB};{2129430:8597BW5I};{2129430:SFATR6IH};{2129430:ZABN4Y4X};{2129430:TCBYKTNZ};{2129430:HDVKI8LR};{2129430:FTX7PLWT};{2129430:M5C6WETQ};{2129430:4YKJF6UR};{2129430:F9XC9DJD};{2129430:EE9GC9VZ};{2129430:GMXVACUY};{2129430:AT8W4WR7};{2129430:MWAJWBEI};{2129430:8JQN59AC};{2129430:6QFFGCRZ};{2129430:CWJEARHH};{2129430:YSSGA26J};{2129430:CTEKR2RK};{2129430:Q5PPMCI5};{2129430:WATPURAW};{2129430:SWS6AK9A};{2129430:9AEEJTXY};{2129430:AMNVQLZB};{2129430:LENDXP9Z};{2129430:7KDI4F8I};{2129430:AZV2WXGD};{2129430:4YKJF6UR};{2129430:N5CTXHZL};{2129430:ZUNQP9TX};{2129430:MX9IEZXA};{2129430:YSSGA26J};{2129430:Q5PPMCI5};{2129430:4YKJF6UR};{2129430:4YKJF6UR};{2129430:M8MIFBYL};{2129430:4YKJF6UR};{2129430:DDF8G6AQ};{2129430:DDF8G6AQ};{2129430:D4ATIBKV};{2129430:CG39XSAA};{2129430:YSSGA26J};{2129430:46H3N3TB};{2129430:4YKJF6UR};{2129430:YSSGA26J};{2129430:CG39XSAA};{2129430:Q5PPMCI5};{2129430:YSSGA26J};{2129430:6U3HIPN7};{2129430:TINQ66XP};{2129430:YSSGA26J};{2129430:46H3N3TB};{2129430:GIGKAEN7};{2129430:CDT7RAQ5};{2129430:46H3N3TB};{2129430:CG39XSAA};{2129430:CG39XSAA};{2129430:YSSGA26J};{2129430:SWS6AK9A};{2129430:46ZL5LAB};{2129430:YBJ73DP8};{2129430:CQY3KLAD}

apa

author

asc

no