Scientific Name Chilabothrus gracilis gracilis Chilabothrus gracilis Photo Martin Reith The nominate form was described and named by Dr. Johann Gustav Fischer (1819-1889), a vertebrate zoologist who, after teaching in several secondary schools, established a secondary school himself. Holotype Syntypes formerly in ZMH: now destroyed ( fide W. Ladiges, in litt ., 18 February, 1971).

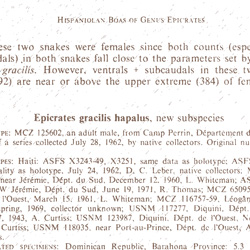

Type Locality Cap-Haïtien, Département du Nord, Haiti.

Subspecies Chilabothrus gracilis gracili s Chilabothrus gracilis hapalus Synonyms Common Name Hispaniolan Gracile Boa, Hispaniola Vine Boa, Dominican Republic Vine Boa.

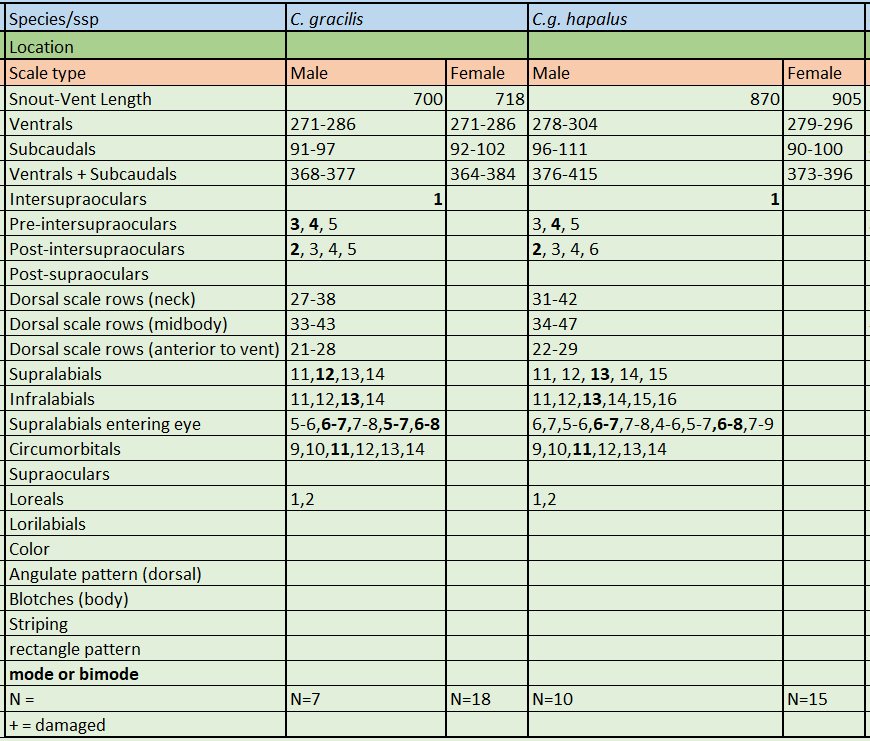

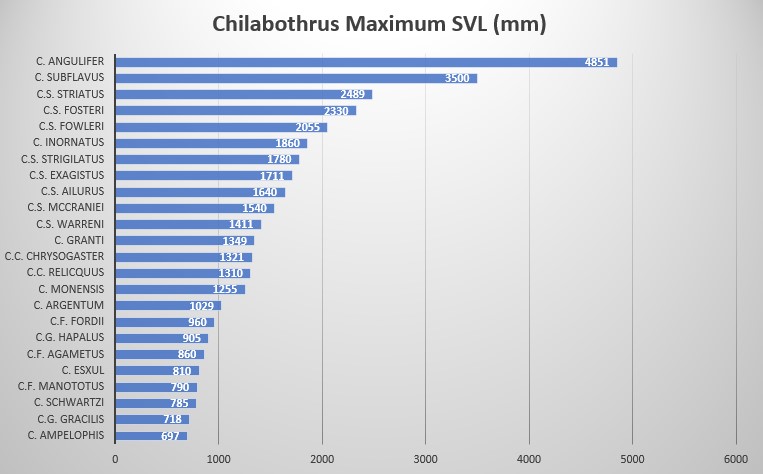

Description and taxonomic notes Maximum SVL is 905 mm, dorsal scales at neck are 27-42, dorsal scale rows at midbody are 33-47, ventral scales in males are 271-304, 271-296 in females, subcaudal scales in males are 91-111, 90-102 in females, ventrals+subcaudals in males are 368-415, 364-396 in females, pre-intersupraoculars are 4, inter-supraoculars are 1, post-intersupraoculars are 2. Laterally compressed and elongated body with a slender neck. An elongate, laterally compressed body, blunt head and large eyes make C. gracilis the most morpologically distinct boid in the genus

Haitian Vine Boa, C. gracilis. Photo Peter Tolson According to data provided by museum specimens, male and female C. gracilis reach a SVL of 700 mm and 718 mm, respectively. In C.g. hapalus the difference in size is very pronounced, with males reaching 870 mm while females reach 905 mm. This large sample size indicates C.g. hapalus is much larger that the nominate species, C.g. gracilis

Remarks: A population of C. gracilis exists at the east side of the Barahona Peninsula in the south of the Dominican Republic. Sheplan and Schwartz examined four specimens from this population and noted that they were similar in size to the C. g. hapalus specimens, however the ventral counts of these snakes resembled closer those of C. g. gracilis . Thus Sheplan and Schwartz suggested that this population represents extreme intergrades between C. g. hapalus and C. g. gracilis . They noted that there are no specimens of C. g. hapalus closer than 150 kilometers to the west (Port-au-Prince, Diquini, Ca Ira) in Haiti, although apparently suitable habitat occurs abundantly between the eastern coast of the Peninsula de Barahona and the base of the Tiburon Peninsula C. g. hapalus , an intergrade form between the two subspecies or a third - yet undescribed - subspecies of C. gracilis . C.g. gracilis & C.g. hapalus meristics. * * Source

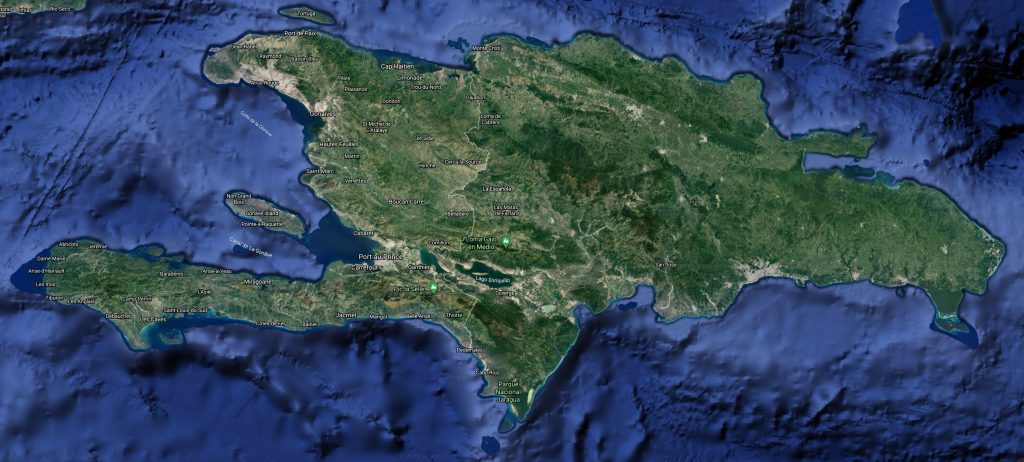

Chilabothrus gracilis. Photo Manuel De Oleo Distribution Hispaniola (Haiti, Dominican Republic). Found up to 175 meters above sea level

C.g. gracilis : Hispaniola; north of the Plaine de Cul de Sac-Valle de Neiba, but only from scattered localities.C.g. hapalus : Haiti; Tiburon Peninsula east to Port-au-Prince and Jacmel. Found from sea level to about 1000 meters

The flags on the map indicate the type locality of Chilabothrus gracilis and Chilabothrus gracilis hapalus. Scroll over the flag to see which type locality occurs at the indicated point.

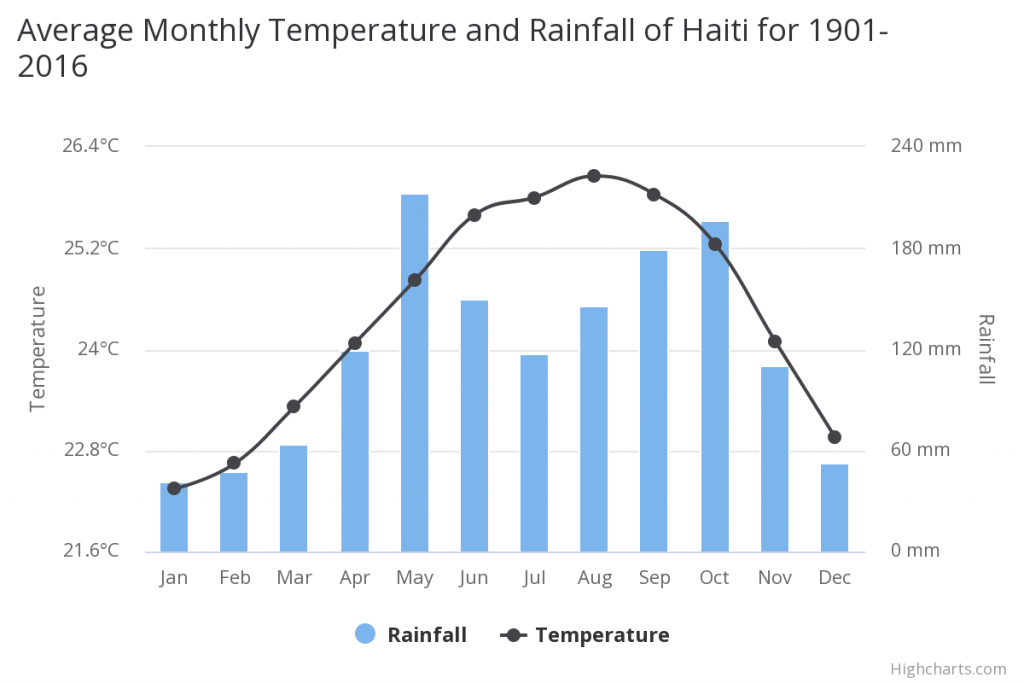

Habitat On Haiti the m ean annual temperature is 24.40°C and the m ean annual precipitation is 1438.40 mm. Located in the Caribbean’s Great Antilles, Haiti has a hot and humid tropical climate. Daily temperatures typically range between 19°C and 28°C in the winter and 23°C to 33°C during the summer months. Northern and windward slopes in the mountainous regions receive up to three times more precipitation than the leeward side. Annual precipitation in the mountains averages 1,200 mm while the annual precipitation in the lowlands is as low as 550 mm. The Plaine du Gonaïves and the eastern part of the Plaine du Cul-de-Sac are the driest regions in the country. The wet season is long, particularly in the northern and southern regions of the island, with two pronounced peaks occurring between March and November.

Mean temperatures have increased by 0.45°C since 1960, with warming most rapid in the warmest season, June-November. The frequency of hot days and hot nights increased by 63 and 48 days per year, respectively, between 1960 and 2003. The frequency of cold days and cold nights has decreased steadily since 1960.

Mean annual rainfall has decreased by 5 mm per month per decade since 1960. The intensity of Atlantic hurricanes has increased substantially since 1980.

C. gracilis is nocturnal and arboreal. It can be found in lowland deciduous woods, especially wooded areas by bodies of water. They have been observed one to four meters above ground in shrubbery, crawling along barbed wire fences, trees large and small, along pastures, streams and lakes. Fortunately this type of habitat still exists along streams and lakes, despite continuing habitat destruction and alteration.

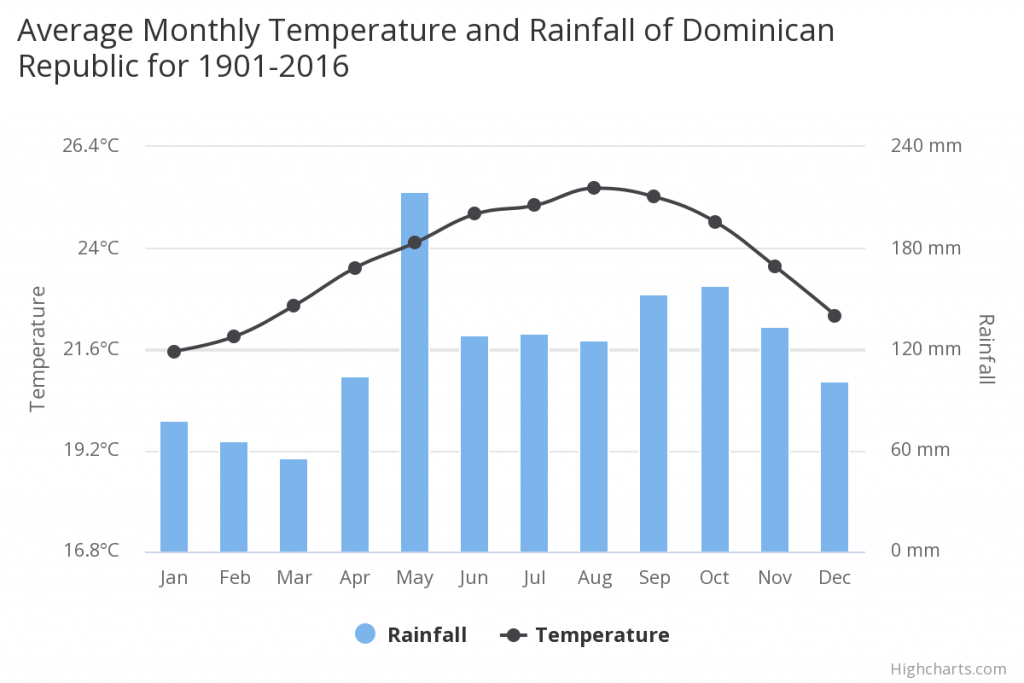

On the Dominican Republic the mean annual temperature is 23.73°C and the mea n annual precipitation is 1448.18 mm.

Note the blunt head, thin neck and large forward looking eyes. Photo Martin Reith Haitian Vine Boa (C. gracilis). Photo Paul Freed Longevity We are unaware of any publications documenting the longevity of Vine Boas. The oldest living specimen we are aware of is a captive bred specimen produced from adults that were imported as adults in 2003. (J. Wagner pers. comm.)

Reproduction & reproductive triggers Tolson reported on two wild caught boas that gave birth to three live babies and 2 unfertilized ovum each on 21 and 24 October. The babies weighed between 2 g and 2.3 g with relative litter masses of 0.192 and 0.224

A gravid female captured at Limbe, Dept. du Nord, Haiti during April 1976 gave birth to five young on 22 September 1976. Data for the young are: total length 301-314 mm (mean 308 mm); SVL 246-254 mm (mean 250 mm); weight 3.8-4.1 g (mean 3.9g). The female measured 890 mm total length, 730 mm SVL and weighed 60.5 g postpartum. The neonates were arboreal and coloration and pattern agreed with the description by Sheplan and Schwartz (1974:114)

Trutnau reported the captive breeding of the Vine Boa by German breeder E. Oswald. He kept a pair of wild caught C. gracilis in a terrarium within his snake room. The room received natural light through the ceiling which was covered with polycarbonate twin-wall sheets. Due to this construction, the snakes were more exposed to weather and seasonal change conditions compared to a terrarium standing inside a house. The temperatures in the room ranged from November-April 20-24°C. and from May-October the room would heat up to 35°C. Food was taken even in the cooler month and copulation occurred April-May with rising temperatures. The male consumed mice even during breeding season voluntarily. The female did not take mice voluntarily and had to be force fed for 6 (!) years with mice. During this period she gave birth to two litters of three babies. The babies were born Sept – Oct length between 22 cm and 26 cm. The smallest Vine Boa had a mass of 2.04 g

Behavior C. gracilis is the sister taxon to C. fordii . Because C. gracilis evolved in sympatry with C. fordii on Hispaniola it became entirely arboreal and C. fordii became entirely terrestrial

Diet Feeds almost exclusively on a diet of anoles. Henderson et al . examined the stomach contents of 33 C. gracilis . The boas preyed solely on Anolis cybotes and A. distichus ). Mean size of prey taken by C. gracilis was 2.4 cm3 (n = 5) and thus significantly smaller than the mean size of prey taken by C. fordii 6.8 cm3 (n = 2)

In captivity adult snakes can be switched over to rodents but do not fare well, long term, on a diet that consists solely of rodents. Trutnau describes the difficulties E. Oswald encountered when feeding newborn Vine Boas. Live anoles as well as live small frogs would be taken immediately. However these prey items were not available in quantities and thus the extremely small boas had to be force fed with small pieces of mice Lepidodactylus lugubris . This species can be bred in quantities without great difficulty

Captive management The Vine Boas require a spacious enclosure with plenty of branches and plant material attached for them to hide in during the day. An elevated water bowl will enable them to find the water. Because they are nocturnal all feeding should be done after lights out. C. gracilis is a hardy captive given the right type of enclosure and proper conditions.

Haitian Vine Boas (Chilabothrus gracilis) in a captive habitat. Photo Ryan Potts Conservation status, threats and population size in nature CITES: Appendix II

IUCN Red List: None

Catalogue of Life: (click here )

The National Center for Biotechnology Information: (click here )

CITES import/export data: (click here )

These snakes remain abundant in some areas, and the CITES listing reflects presumed threats emanating from international trade for the pet industry, which currently are not applicable to these speciesC. gracilis is considered stable in number. Alteration of its habitat and loss of prey items are the current threats facing this slender oddity.

Habitat destruction and deforestation in particular are two of the major threats to wildlife in Haiti. The demand for charcoal (for local consumption as well as export) dramatically deteriorated the situation. Loss of primary forest is a major driver of mass extinction events, particularly in areas with a high degree of endemism such as Haiti C. g. gracilis and C. g. hapalus considering that these boas are more adapted to mesic situations and nowhere very common

The CIA World Factbook lists the following environmental threats for Haiti: extensive deforestation (much of the remaining forested land is being cleared for agriculture and used as fuel); soil erosion; overpopulation leads to inadequate supplies of potable water and and a lack of sanitation; natural disasters. For the Dominican Republic: water shortages; soil eroding into the sea damages coral reefs; deforestation

The map below illustrates the extent of habitat destruction and alteration due to development and agriculture.

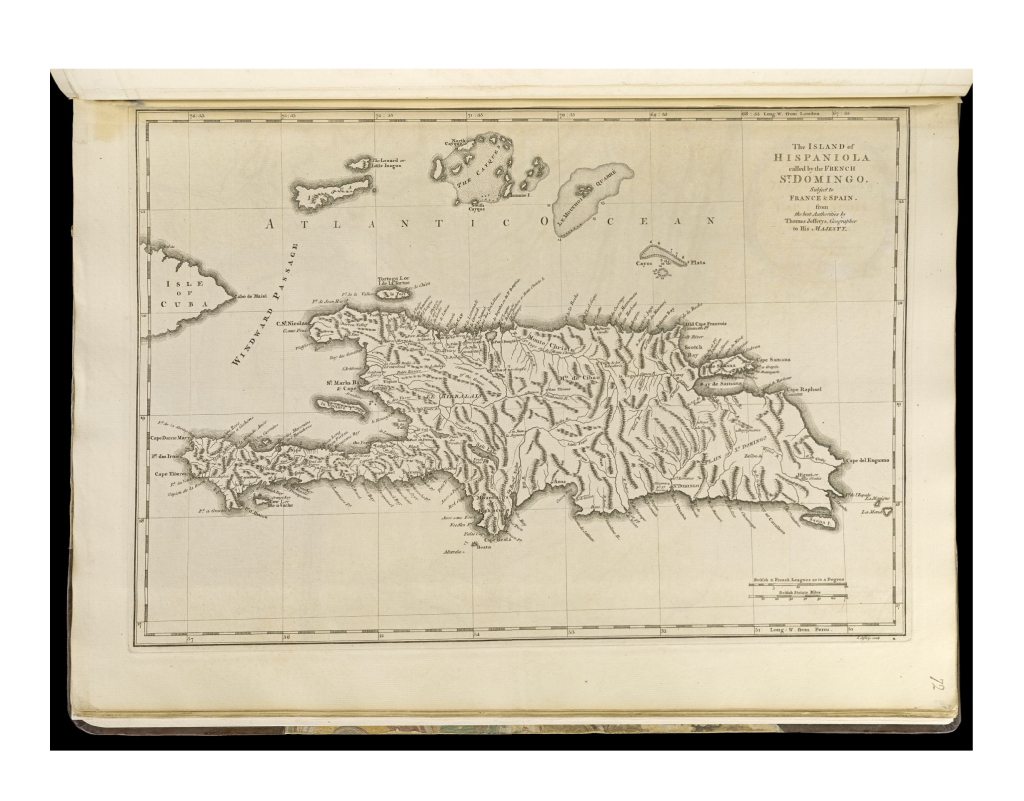

Hispaniola (C.f. fordii, C.f. agametus, C.f. manototus, C.g.gracilis, C.g. hapalus, C. s. striatus, C.s. warreni, C.s. exagistus) Early map of HIspaniola, 1768. Population in captivity We are aware of but a single C. gracilis in the possession of an American private collector. This enigmatic boa was, at one time, available through importers on a regular basis. Records indicate it was last imported into the US in 2003. It is unknown where the boas are at the time of this writing.

On display in these Zoos We are unaware of any Chilabothrus gracilis on display in any public institutions or zoo collections worldwide.

Continue to Chilabothrus gracilis hapalus

Citations

{2129430:QZLSEPK2};{2129430:QZLSEPK2};{2129430:WPYXP4KX};{2129430:QZLSEPK2};{2129430:B5KXQKJ6};{2129430:FKN8ZAUB};{2129430:8597BW5I};{2129430:SFATR6IH};{2129430:TNMD7KFI};{2129430:ZABN4Y4X};{2129430:TCBYKTNZ};{2129430:HDVKI8LR};{2129430:FTX7PLWT};{2129430:M5C6WETQ};{2129430:FTYCYVBR};{2129430:MRVBSCBF};{2129430:F9XC9DJD};{2129430:GMXVACUY};{2129430:AT8W4WR7};{2129430:HR9F33X3};{2129430:MYKEFDQ6};{2129430:8JQN59AC};{2129430:6QFFGCRZ};{2129430:CWJEARHH};{2129430:6SCYJ9AY};{2129430:PCLHMKXD};{2129430:TRWL9T99};{2129430:C794F8RH};{2129430:SWS6AK9A};{2129430:AMNVQLZB};{2129430:4WUMTCH6};{2129430:WPYXP4KX};{2129430:WPYXP4KX};{2129430:QHW3LQDU},{2129430:9NLTZC3L};{2129430:WPYXP4KX};{2129430:FTYCYVBR};{2129430:UUNHHSWB};{2129430:QHW3LQDU};{2129430:9N4BJA59};{2129430:QHW3LQDU};{2129430:YC4AVSKU};{2129430:QDXXC4M2};{2129430:9N4BJA59};{2129430:MJRZRYQ5};{2129430:QDXXC4M2};{2129430:38WM9CUV};{2129430:8M7APEJU};{2129430:LHQ34MUW};{2129430:MJRZRYQ5};{2129430:CQY3KLAD}

apa

author

asc

no