Scientific Name Chilabothrus monensis

Juvenile Chilabothrus monensis. Photo Peter Tolson Described and named by Jonathan Adolf Wilhelm Zenneck (1871–1959). Zenneck was a brilliant scientist and electrical engineer who also spoke Latin, Greek, French and Hebrew. He directed the Deutsches Museum in Munich and rebuilt it after World War II. Holotype Syntypes: Universtat Hamburg Zoologisches Institut und Zoologisches Museum (ZMH): now destroyed; 5 of the syntypes in the HZM were lost during World War II ( in litt ., W. Lädiges, February 18, 1971)

Type Locality Mona Island, near Puerto Rico.

Synonyms (ensis ) is a Latin adjectival suffix meaning “pertaining to” or “originating in" Mona Island, hence monensis . Common Name Mona Island Boa, Mona Boa.

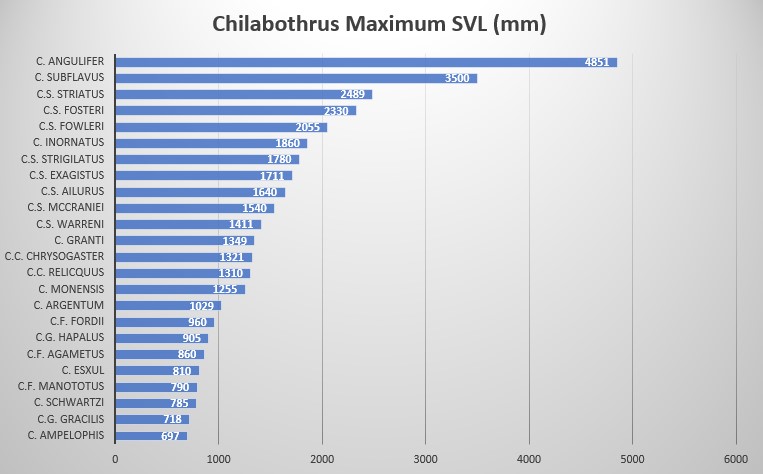

Description and taxonomic notes Maximum SVL is 1027 mm (700-1027) in males, 1255 mm (722-1255) in females, scale rows at neck are 34-39, scale rows at midbody are 39-47, 23-31 anterior to vent, ventral scales in males are 261-272, 261-266 in females, subcaudal scales in males are 80-81, in females 82-84, ventrals+subcaudals in males are 345-347, 345-348 in females, pre-intersupraoculars are 3, inter-supraoculars are 1, post-intersupraoculars are 5, the lowermost scale row not alternating a large and small scale, supralabials 13 (modally) with typically 2 supralabials (6-7 modally) entering the eye, infralabials 15 (modally), circumorbitals 11 (modally), loreals 1 (modally), body blotches 47-73, tail blotches usually 10-22 C. monensis (and C. fordii ) are the only members of the genus born with a gray or grayish-brown ground color

C. monensis meristics. * * Source

Tolson and Henderson cite Meerwarth who supposedly reported a specimen of 1010 mm total length

Distribution Isla Mona.

Habitat The entirety of Mona Island is designated as critical habitat

Rainfall is averaged at about 800 mm a year. The dry season is from November through April and the wet season runs May through August. The boa can be found in trees that consist of Gymnanthes lucida on the coast; inland the suitable trees are Schaefferia frutescens , Capparis cynophallophora and C. flexuosa . The coastal terrace has been cleared and planted with Australian Pine (Casuarina equisetifolia ) and West Indian mahogany (Swietenia mahogani ). Both of the trees on the coastal terrace were planted by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the late 1930’s. (USFWS 1984).

C. monensis foraging at night for prey on Mona Island, near Sardinera beach, on the plateau next to the cliff. Photo Derick Hernandez Hernandez remarks about the photo above on Mona Island: “Mona Island, near Sardinera Beach, on the plateau next to the cliff, October 21, 2019 around 9 PM. We saw two that night, a little one on the bushes (around 8 inches) and a big one on the ground (around 3 feet). I lived 4 months on the island working with sea turtles and at that time I did not see more than 10, they rarely found themselves in the camp, they were more common on the plateau.”

Tolson et al .

It was determined boas of different size and age inhabited separate horizontal zones. Boas that measure 400 mm (< one year old) and less were found most often in Ficus citrifolia , Tillandsia utriculata and Eugenia species at an average height of one and a half meters. The young used a total of seventeen tree and shrub species with no preference for a single species. The boas referred to as young-of-the-year measure 401 mm to 500 mm. This class used fifteen species of trees and shrubs and was found at a height of 1.3 meters. The two species most likely to harbor boas are Antirhea acutata and F. citrifolia . The middle class (subadult) of boas measure 501 mm to 600 mm and use eighteen species of trees and shrubs and are found at a height of 1.7 meters. The boas are most often found in both A. acutata and F. citrifolia . Subadult boas that measure 601 mm to 700 mm were found in fourteen species of trees and shrubs at a height of 1.8 meters. The boas were most often found in F. citrifolia and Caesalpinea monensis . Adult boas measure greater than 700 mm SVL and were found in nineteen species of trees and shrubs at a height of two meters. The boas were found most often in F. citrifolia and Clusia rosea . Interestingly, thirty-nine boas of all classes were found in the bromeliad T. utriculata , seven of which were found in trees

C. monensis class data (N=68). Raw data taken from Longevity C. monensis has been kept in several institutions, however, longevity data is largely lacking. Slavens and Slavens report the presumed maximum age of a wild caught animal residing in the Toledo zoo to be 11 years

Reproduction Mona Boas reach sexual maturity at about 800 mm SVL; it takes about five years to reach this size. All eight gravid females Tolson captured during his study measured from 905 mm to 1255 mm.

Slavens reports the following reproduction data

1994 TOLO 0.0.10 born during 1994. 1996 TOLO 0.0.3 born during 1996. In 1989 Tolson reports the following reproduction data

4 litters in wild caught females: 10 August, 12 August, 28 August, 12 September. 4 litters from captive breedings: 14 Jul (2), 17 July, 20 July. C. monensis begin mating in the month of January & February Behavior The Mona Island Boa is nocturnal and semi-arboreal. Boas of all age classes use a wide selection of trees and vegetation. Tree density and interconnectivity appear to be more important than tree species; this allows them to move and forage freely without having to descend to the ground. The boas are found in greater numbers where a higher density of prey occurs, most notably sleeping Anolis cristatellus , and higher perch height (Tolson 1988). Higher densities of Ameiva exsul also have an effect on the higher numbers of Boas per locality (Tolson 1991). A wide variety of tree structure that provides three-dimensional features such as spreading crowns, aerial roots, compound trunks, etc., provides ideal habitat for foraging and resting. The boas avoid habitat significantly altered by feral goats or congregations of goats (Tolson 2007). Younger boas may potentially become prey to land crabs (Gecarainus and Coenobita clypeatus ); Tolson suspects wounds and missing sections of tails may be crab related (Tolson 1988).

Diet Very little data exists on the natural prey items of the Mona Boa. One account stated “It is believed that the bulk of this rare snake’s diet consists of bats.” Anolis cristatellus (A. monensis ) was found in its stomach Anolis cristatellus and Ameiva alboguttata were the two most abundant reptiles on the island. Tolson et al. state adult C. monensis prey primarily on Rattus rattus while the smaller boas feed primarily on A. monensis. A. monensis and Eleutherodactylus monensis, food prey staples for the younger boas, use the bromeliad T. utriculata as refugia because their large leaves retain water between periods of rain Dendroica petechia (Yellow Warbler) are also taken by adults

Captive management Spacious terrariums with plenty of climbing and basking branches are required and utilized. The boas seek refuge during the day and will use any area that is hidden and dark. Elevated water bowls allow for easy access to drinking water and soaking while opaque.C. monensis readily take frozen thawed appropriately sized mice and pink rats every five to seven days. The boas have a rapid metabolism and will shed often, indicating quick growth.

Conservation status, threats and population size in nature CITES: Appendix I

IUCN RED List: Endangered (EN) (click here )

Catalogue of Life: (click here )

The National Center for Biotechnology Information: (click here )

CITES import/export data: (click here)

USFWS status: (click here )

FWS Focus: No

Ruling that listed C. monensis as Threatened (TH) and the establishment of Mona Island as Critical Habitat. When the Mona Island Boa was listed March 6, 1978, the FWS considered the boa as having both high degrees of threat and recovery potential. As of 2014 the FWS was of the opinion the population of the boa was stable. C. monensis is one of few boas that can be found in excess of 40 to 125 individuals per hectare Anolis and the boas. Schmidt visited the Island in 1919 and found feral herds and droves of cattle, pigs and goats roaming freely on the plateau

The CIA World Factbook lists the following environmental threats for Puerto Rico: soil erosion; occasional droughts cause water shortages; industrial pollution

Mona Island On display in these Zoos Toledo Zoological Garden

Marvelous Monas Chilabothrus monensis

Chilabothrus monensis Mona Island Boa -Pattern

Chilabothrus monensis

Chilabothrus monensis Mona Island Boa

Chilabothrus monensis

Chilabothrus monensis Mona Island Boa

Chilabothrus monensis

Chilabothrus monensis Mona Island Boa - Head

Chilabothrus monensis

Chilabothrus monensis Mona Island Boa

Chilabothrus monensis

Chilabothrus monensis Mona Island Boa

Chilabothrus monensis

Chilabothrus monensis Mona Island Boa

Chilabothrus monensis

Chilabothrus monensis Mona Island Boa

Continue to Chilabothrus schwartzi

Citations

{2129430:FKN8ZAUB};{2129430:WPYXP4KX};{2129430:ET6VD3RD};{2129430:FKN8ZAUB};{2129430:LBGADMLZ};{2129430:FEDSP6RC};{2129430:8597BW5I};{2129430:SFATR6IH};{2129430:ET6VD3RD};{2129430:5UR46KHT};{2129430:458TVYKN};{2129430:TCBYKTNZ};{2129430:IFAFZEGF};{2129430:HDVKI8LR};{2129430:FTX7PLWT};{2129430:M5C6WETQ};{2129430:FTYCYVBR};{2129430:F9XC9DJD};{2129430:WPYXP4KX};{2129430:GMXVACUY};{2129430:AT8W4WR7};{2129430:MWAJWBEI};{2129430:V7BRQ3FB};{2129430:8JQN59AC};{2129430:6QFFGCRZ};{2129430:CWJEARHH};{2129430:6SCYJ9AY};{2129430:ERLBGK22};{2129430:PCLHMKXD};{2129430:TRWL9T99};{2129430:TL8DLU9R};{2129430:SWS6AK9A};{2129430:AMNVQLZB};{2129430:WPYXP4KX};{2129430:9N4BJA59};{2129430:4WUMTCH6};{2129430:8SG5T3F5};{2129430:WJLHMCI8};{2129430:QHW3LQDU};{2129430:LBGADMLZ};{2129430:WZRX6DCW};{2129430:ET6VD3RD};{2129430:WJLHMCI8};{2129430:WJLHMCI8};{2129430:ICMBFAPP};{2129430:BMRNKRE9};{2129430:BMRNKRE9};{2129430:QHW3LQDU};{2129430:RDH2FB32};{2129430:5UR46KHT};{2129430:WJLHMCI8};{2129430:WZRX6DCW};{2129430:VIMCTQSE};{2129430:ET6VD3RD};{2129430:WJLHMCI8};{2129430:CQY3KLAD};{2129430:W2SCN3V8};{2129430:XK6LXCSK};{2129430:QQ9ZHP5R}

apa

author

asc

no