Scientific Name Chilabothrus striatus C. striatus, Monte Plata Province, Dominican Republic. Photo Pedro Rodriguez The nominate form was described and named by Dr. Johann Gustav Fischer (1819-1889), a vertebrate zoologist who, after teaching in several secondary schools, established a secondary school himself. Holotype Syntypes formerly in ZMH, now destroyed.

Type locality Santo Domingo and St. Thomas; later restricted to the city of Santo Domingo, Distrito Nacional, República Dominicana

Synonyms Homalochilus 101 ]Homalochilus striatus 103 ] [104 ] [105 ] [106 ] [tab II ]Homalochilus multisectus 71 ]Homalochilus striatus Homalochilus striatus Homalochilus striatus 86 Homalochilus striatus Homalochilus striatus Epicrates striatus 97 ]Epicrates striatus Epicrates striatus 58 ] [59 ] [60 ]Epicrates angulifer var. striatus 6 ] [7 ]Epicrates striatus Epicrates striatus 39 ]Epicrates striatus Epicrates striatus Epicrates striatus Epicrates striatus 12 ]Homalochilus striatus Epicrates striatus Epicrates striatus 207 ]Epicrates striatus striatus Epicrates striatus striatus Epicrates striatus striatus Epicrates angulifer striatus 75 ]Epicrates striatus striatus 314 ] [315 ] [316 ] [317 ] [318 ]Epicrates striatus striatus Epicrates striatus striatus 70 ] [71 ] [72 ]Epicrates striatus striatus Epicrates striatus striatus Epicrates striatus Epicrates striatus striatus Epicrates striatus Henderson, Schwartz & Inchaustegui, 1984: 94Epicrates striatus striatus Epicrates striatus striatus Epicrates striatus Epicrates striatus Epicrates striatus Epicrates striatus striatus Epicrates striatus Crother, Powell et al, 1999: 114 [129] [157] [158]Epicrates striatus Epicrates striatus Tipton, 2005: 46Epicrates striatus Epicrates striatus striatus 134 ] [135 ]Chilabothrus striatus Epicrates striatus Chilabothrus striatus Chilabothrus striatus The name striatus is derived from the Latin for "striated" or "lined". Subspecies Chilabothrus striatus striatus: Chilabothrus striatus exagistus: Chilabothrus striatus warreni: Common Name Hispaniolan Boa, Haitian Boa (Hispaniola-wide), Fischer’s Boa.

Description and taxonomic notes The first mention of the Hispaniolan Boa Chilabothrus striatus was in the work of Fischer, 1856. Meerwarth investigated material collected by various sources from Haiti and Santo Domingo (today’s Dominican republic), he did not respect striatus as a valid species and considered it a subspecies or “variety” (var.) of the Cuban Boa, thus naming it Epicrates angulifer var. striatus.

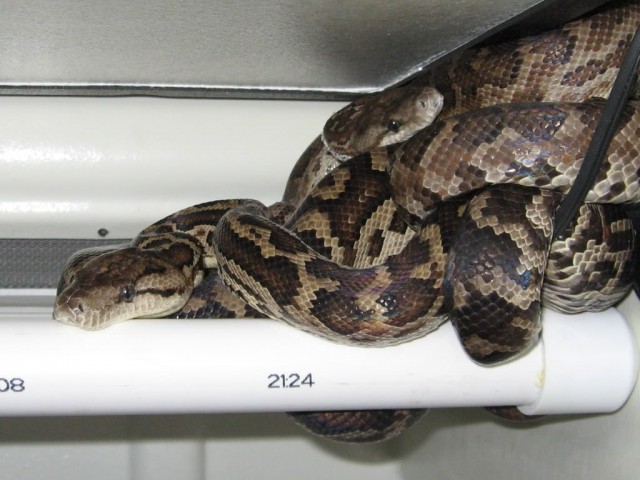

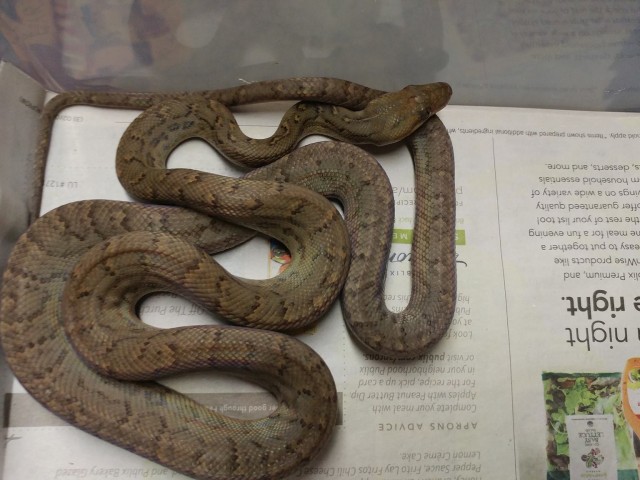

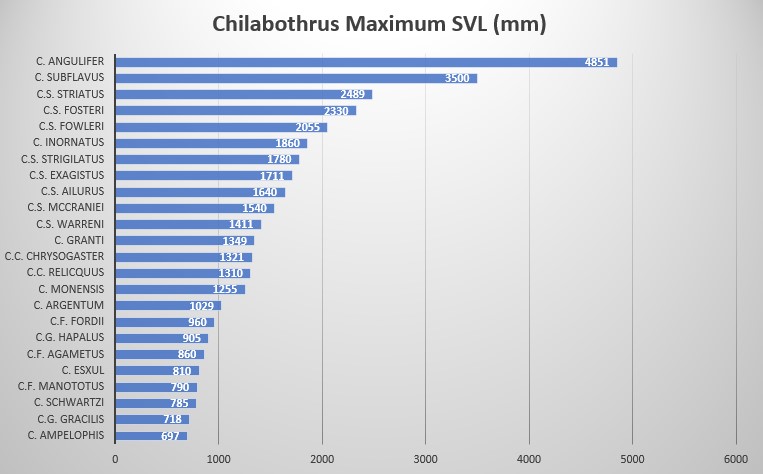

The Haitian Boa, Chilabothrus striatus. Photo Dick Bartlett The boa reaches lengths of up to 2489 maximum SVL mm; generally males are 2330 SVL and females 2055 SVL, ventral scales 270-299 in males and 266-298 in females, subcaudals are 76-102 in males and 76-94 in females, males have 353-390 subcaudals + subcaudals and females 343-387, dorsal scale rows on neck are 34-39, dorsal scale rows at midbody are 35-36, anterior to vent 22-31 scales, 1 or 2 intersuprocular scales, 3 or 5 (modally) preintersupraocular scales, 5 (modally) post-intersupraocular scales, supralabials 14 or 15 (modally) with usually two (7-8 or 8-9 modally) or three (7-9 modally) supralabials entering the eye, infralabials 18 or 19 (modally), loreals 1 or 2 (modally), 60 to approximately 122 body blotches, tail blotches can be missing or as many as 28

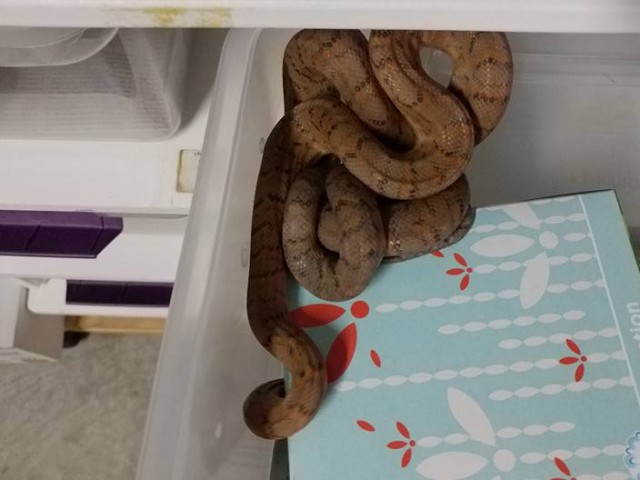

It should be noted 2 specimens (ASFS X81110 and ASFS X9276) of C.s. striatus exhibited erythrism from a location southwest of Milches, El Seibo, Dominican Republic. A third specimen (ASFS V18525) from a location near La Mata, Sanchez Ramirez Province exhibited the same reddish coloration. This specimen was dark orange with grayish orange blotches. Fowler and Schwartz saw a dead erythristic C.s. striatus east of Sabana de la Mar and asked locals about “culebras coloradas” (red snakes). Locals were familiar with this term and coloration of the boas. Apparently all the erythristic snakes can be found on the eastern end of the island. The erythristic phase so in vogue at the moment has been well documented since, at least, 1971

Erythristic C. striatus. Photo Graham Reynolds Cochran investigated a specimen from Isla Tortuga but found that “The specimen from Tortuga Island does not seem to differ specifically from the Haitian form.” warreni was reasoned

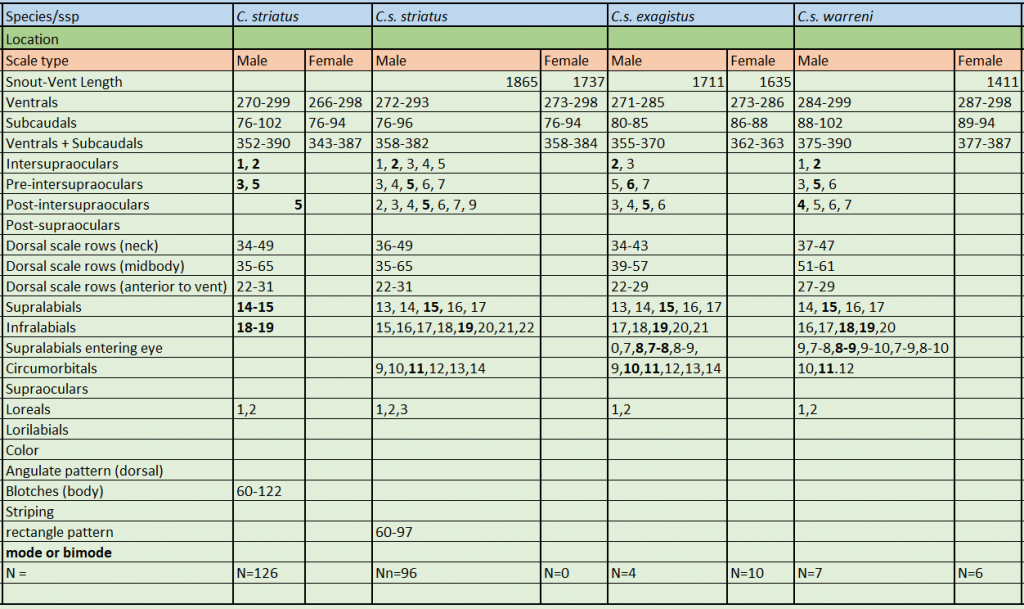

Erythrism in Fischer’s Boa (C. striatus). Photo Paul Freed C.s. striatus, C.s. exagistus, C.s. warreni meristics. * * Source C.s. warreni were captured-hence the missing data for this species. Evolution No fossil or subfossil remains of C. striatus have been found to date. A fossil found on Abaco was considered to be C. striatus C. exsul and no longer C. striatus

A molecular phylogeny based on CYTB locus found that Chilabothrus striatus is most closely related to C. exsul, C. schwartzi and C. argentum: the lineages split about 2.2 Mya. The next closest relative to the clade is C. strigilatus, from which the lineages split 2.6 Mya. Then there is C. chrysogaster, from which the lineages split 4.1 Mya

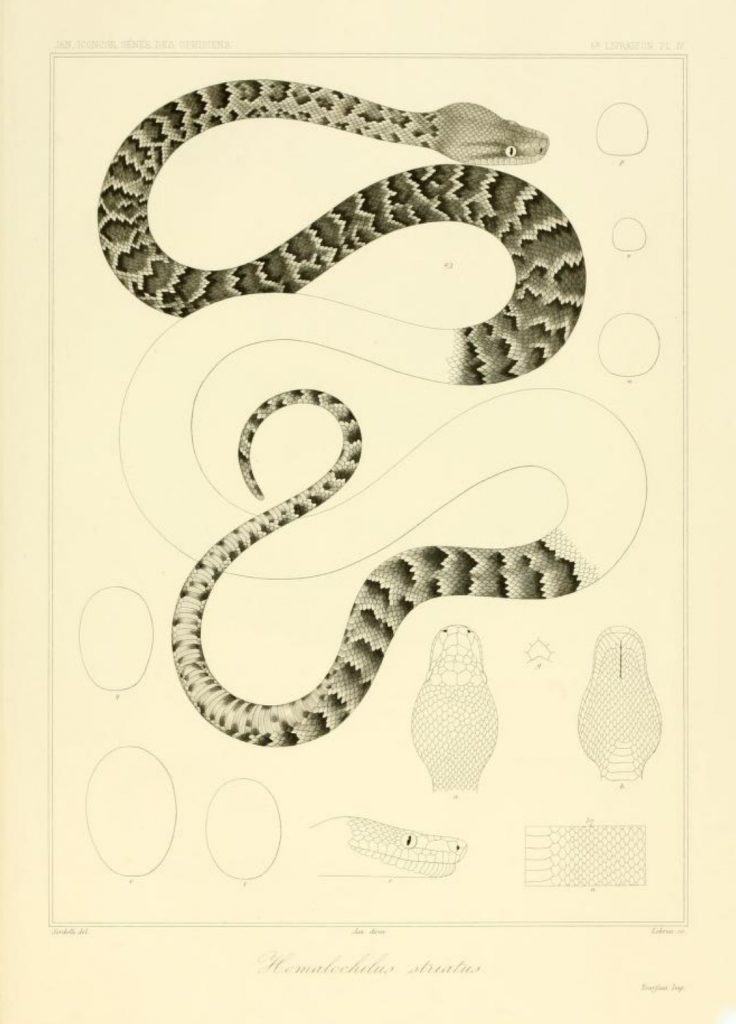

Homalochilus striatus by Jan, 1864. Distribution Hispaniola; Île de la Gonâve; Isla Saona; intergrades with E. s. exagistus . C. striatus does not cross the Crooked Island Passage (Sheplan & Schwartz, 1974).

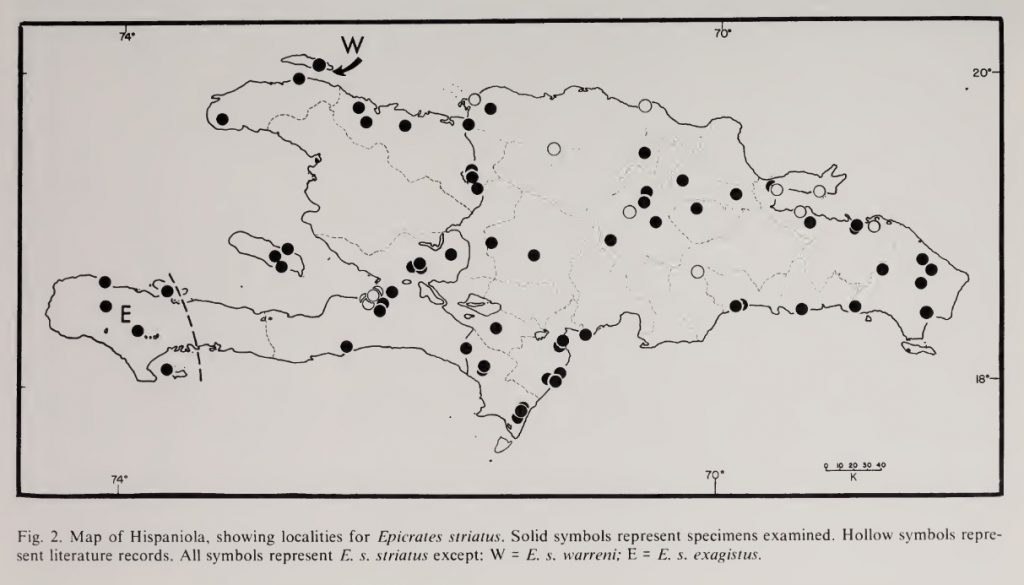

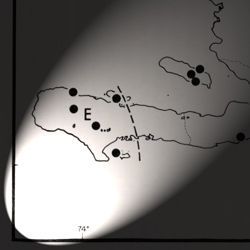

Distribution map of C.s. striatus, C.s exagistus & C.s. warreni. * * Source:

Three subspecies of Chilabothrus striatus occur on Hispaniola. The flags on the map indicate the type locality of a subspecies. Scroll over to see which subspecies has its type locality at the indicated point.

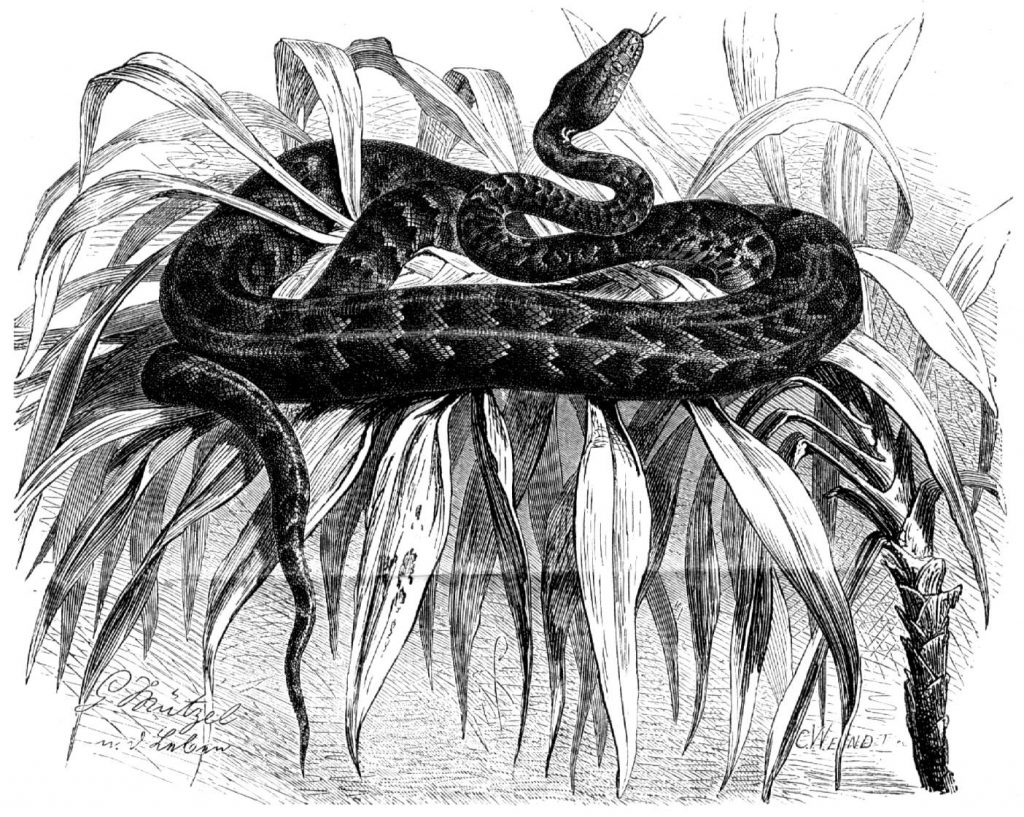

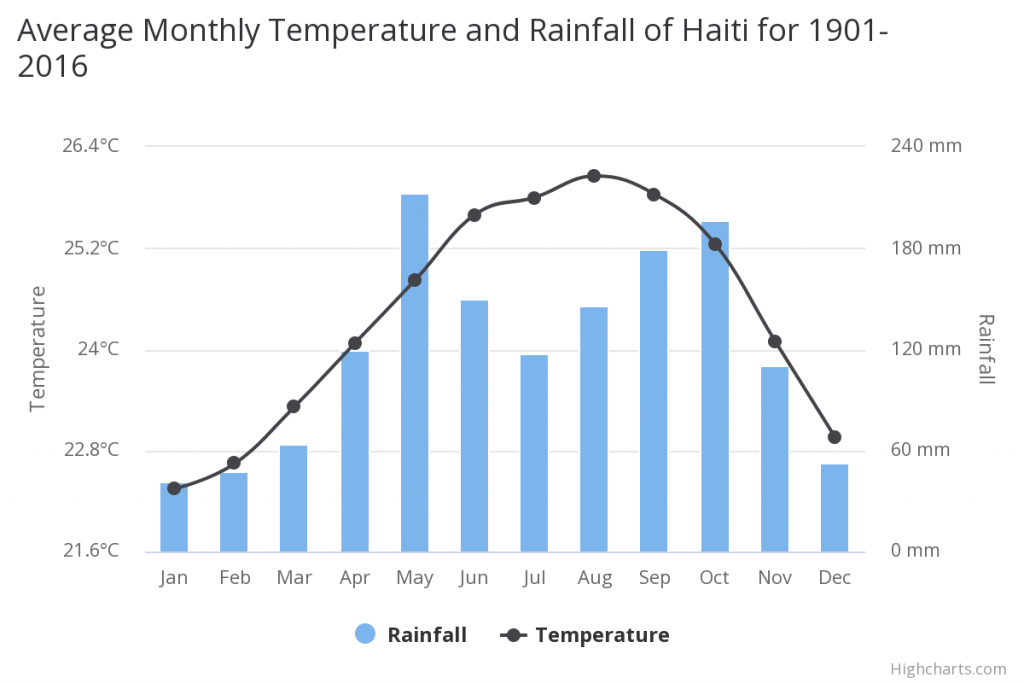

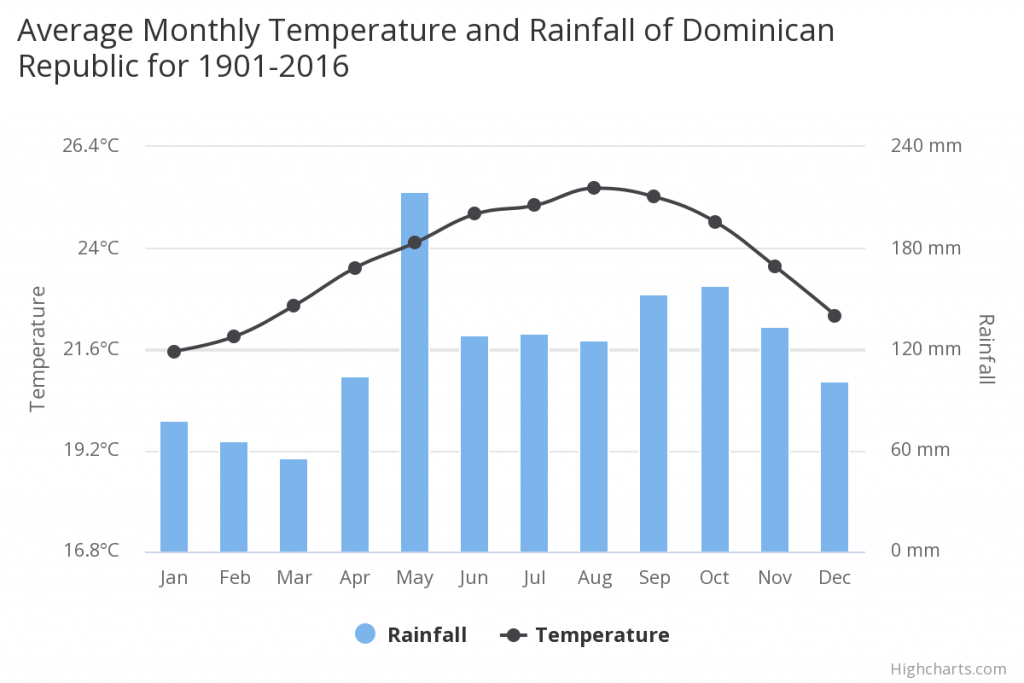

Drawing of an Hispaniola Boa from Brehms Thierleben, 1878. Habitat On Haiti the m ean annual temperature is 24.40°C and the m ean annual precipitation is 1438.40 mm. Located in the Caribbean’s Great Antilles, Haiti has a hot and humid tropical climate. Daily temperatures typically range between 19°C and 28°C in the winter and 23°C to 33°C during the summer months. Northern and windward slopes in the mountainous regions receive up to three times more precipitation than the leeward side. Annual precipitation in the mountains averages 1,200 mm, while the annual precipitation in the lowlands is as low as 550 mm. The Plaine du Gonaïves and the eastern part of the Plaine du Cul-de-Sac are the driest regions in the country. The wet season is long, particularly in the northern and southern regions of the island, with two pronounced peaks occurring between March and November.

The iconic Haitian Boa, C. striatus. Photo Graham Reynolds Mean temperatures have increased by 0.45°C since 1960, with warming most rapid in the warmest season, June-November. The frequency of hot days and hot nights increased by 63 and 48 days per year, respectively, between 1960 and 2003. The frequency of cold days and cold nights has decreased steadily since 1960. Mean annual rainfall has decreased by 5 mm per month per decade since 1960. The intensity of Atlantic hurricanes has increased substantially since 1980.

C. s. striatu s occurs from sea level to 1220 meters in the Sierra Martin Garcia and the Cordillera Central

Chilabothrus striatus. Photo Dick Bartlett It can usually be found in mesic, forested areas that are both sparse and dense. They are commonly found in areas that are mesic in nature but also inhabit fairly dry forests. Sheplan and Schwartz found a DOR boa in Elias Pina; they assume the boas can also be found in upland Valle de San Jaun as it is also xeric scrub habitat. The snakes are usually encountered at night while foraging for prey. The boas have been taken in daylight from hollow logs, straw roofing, rotten tree stumps and rotten palm logs

Longevity C. striatus are long lived. Wagner (pers. comm.) has an old male from one of the authors that was an adult when imported in the early 2000’s. Bowler listed the maximum age for a Epicrates striatus ssp . with 22 years and one month Chilabothrus strigilatus ssp. , since no Chilabothrus striatus warreni and very few C. s. exagistus have been exported and kept. The only age record we could find about C. s. striatus confirms an age of 6 years and 8 months at the National Zoological Park

Reproduction C.s. striatus : Slavens & Slavens report the following reproduction data

1974 FORT bred during 1974.FORT bred during 1976.CITV 0.0.18 born 28 Sep 1980.NEWN 0.0.20 born during 1980.NEWN 0.0.34 born during 1981.PPET 0.0.14 born during 1985.PPJM 0.0.29 born during 1986. Male and female housed together Feb 9-13/86. Copulation dates not recorded. On Aug 20th female gave birth to 29 normal and 2 deformed babies, and approx 12 infertile egg masses. Deformed babies (still in membranes) and infertile masses were eaten by female. In 1985 same pair caged together Feb 16-19, March 10-21, and April 1-7. Copulation appeared to occur during all these periods, but dates not recorded. On Aug 21/85 female gave birth to 32 normal babies and 3 infertile masses. Female ate infertile masses.COTE 0.0.5 born during 1988.COTE 0.0.28 born during 1989.NEWN 0.0.5 born during 1989.ROYN 0.0.6 born during 1989.MIEP 0.0.12 born during 1990. Copulation observed 6 Mar – 5 Apr. 0.0.12 young born 15 Aug 90, 3 died within one month. Young would not feed.TOLO 0.0.17 born during 1990.COTE 0.0.31 born during 1991.ROYN 0.0.8 born during 1991.ROYN 0.0.3 born during 1993.

Tolson reported about a wild caught female captured at Limbe, Haiti gave birth to 6 babies on 16 September C. striatus , four and a half years of age, reproduced successfully at the Toledo Zoological Gardens

Schmidt reported a female from Los Quemados measuring two meters in length and “about as thick as a man’s wrist”, containing 26 eggs, measuring from 30 to 40 mm. by 25 mm

Huff reported to have examined “some interesting snakes which were reportedly the result of hybridization between the Hatian boa (Epicrates s. striatus ) and the Colombian rainbow boa E. cenchria maurus”. Currently classfied as Chilabothrus striatus and Epicrates maurus respectively. Huff considers the hybridization of the different subspecies of E. striatus (sensu lato ) possible, however, he did not mention any hybrids he is aware of

Haitian Boas (C. striatus) mating. Behavior C. striatus is nocturnal and mostly arboreal in nature Anolis . Large boas have been observed at night loosely coiled on branches of low trees. Diurnal behavior includes resting on large branches, in the shade, at heights of five to twenty meters off the ground. They can be also be found in limestone crevices, hollow trees, and bird nests

Diet Henderson et al. C. striatus and found 28 prey items. The boas go through an ontogenetic shift in prey items as they mature. Boas that measure less than 60 cm SVL preyed primarily on Anolis . Boas measuring 60 to 80 cm SVL preyed on both Anolis and small rodents. Those boas larger than 80 cm SVL preyed on birds and rats (Rattus rattus ). Once boas’ measurements exceeded 105 cm SVL their diet consisted entirely of rats. In 1974 an extremely large C. striatus (248.9 cm total length) was found that contained remains of a Plagiodontia in its digestive tract (C.A. Woods, reported in Ottenwalder, 1985). The prey items of the 133 boas examined consisted of:

2.1% lizards (Anolis coelestinus, A. cybotes, A. sp ) 5.2% birds (Dulus dominicus, Quiscalus niger, Coereba flaveola (?)) 92.7% mammels (Rattus rattus, Mus musculus ) It was determined the mean size of anoles taken (including C. fordii and C. gracilis ), to be 3.6 cm³ (2.5 to 4.6 cm³). C. striatus preyed upon the larger anoles (of a species) more so than any other boid species. They posit the large boas feed only upon large prey because the prey is both ecologically and geographically abundant and widespread

Some Chilabothrus species have been reported to prey on bats. However, this behavior has not been reported for C. striatus. The below image is supposedly the first documentation and maybe even the first observation of C. striatus preying on bats.

This is probably the first photographic evidence of C. striatus preying upon bats. Located in Cuevas de Pomier, San Cristobal, Dominican Republic. Found at 9:00am at ca. 350 above sea level. Photo Thais Herrera C. striatus seems to have well adapted to the environmental changes that followed after the arrival of the Europeans on the Island. The species readily adapted to mice and rats as prey species and is thriving on this diet. Its original prey source, native birds and rodents (Brotomys , Isolobodon and Plagiodontia ) and insectivores (Nesophontes ) became extinct on Hispaniola as a consequence of European arrival. The prey shift was completed in the early 20th century

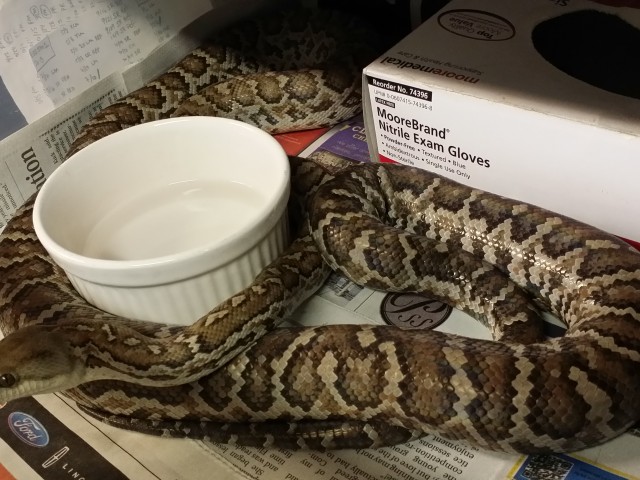

Captive management In captivity the boas will thrive if given ample space, several places to hide and branches to climb and rest upon. In addition to a water bowl a separate soaking container is recommended. Offspring will only take ectothermic prey such as anoles. Once feeding regularly they can be converted to pink mice by scenting them with anoles. Adult boas that become recalcitrant feeders can almost always be induced to take chicks or appropriately size fowl.

C. striatus mating. A gravid female Hatian Boa. As stated above, young Chilabothrus striatus seem to prefer lizards of the genus Anolis as prey items. While Anoles are not always available, another – as of yet untested – alternative to anoles might be small parthenogenetic geckos like Lepidodactylus lugubris . This species can be bred in quantities without great difficulty

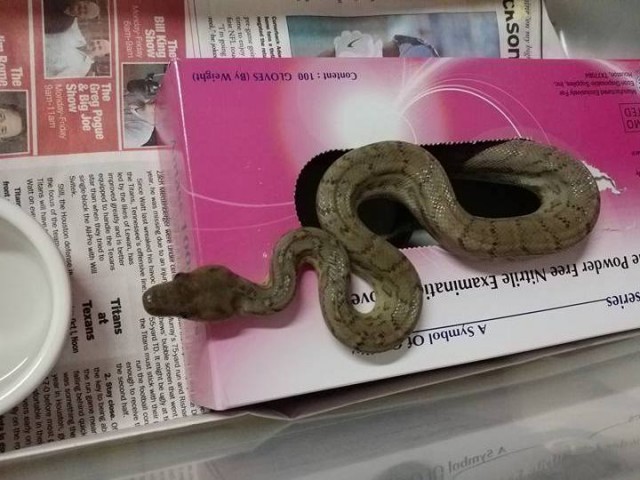

Newborn C. striatus (Haitian Boas) Starting newborn Haitian Boas on Anolis sagrei Two breeders reported the feeding of fish. Stoel attempted to feed a trio of young C. striatus by putting live Guppies (Poecilia reticulata ) in the water basin of the terrarium. While on the first day and night the snakes didn’t show interest in the fishes and slept in the water basin with the Guppies, he noticed on the next evening all but one adult Guppy had disappeared

Verstappen reported a case of a litter of C. s. striatus that wouldn’t feed voluntarily, even though a variety of prey was offered (young mice, frogs, lizards and birds). On the observation from another breeder that his C. striatus had eaten a fish, the breeder tried this prey item. He caught some Sticklebacks (probably Gasterosteus aculeatus ), killed them and took away the spines. In the evening he put the Sticklebacks on the branches in the terrarium and the next morning they were all gone. Two weeks later he repeated the procedure, again with the same result. Subsequently he fed the young C. s. striatus dead Goldfish (Carassius gibelio )

Conservation status, threats and population size in nature CITES: Appendix II

IUCN Red List: Least Concern (LC)

Catalogue of Life: (click here )

The National Center for Biotechnology Information: (click here )

CITES import/export data: (click here )

The 21 July, 2015 IUCN rating of LC is described as follows:

This species is listed as Least Concern because of its large extent of occurrence, the population trend appears to be stable, the species inhabits different habitats including disturbed situations, and it occurs in many protected areas. These snakes remain abundant in some areas, and the CITES listing reflects presumed threats emanating from international trade for the pet industry, which currently are not applicable to these species Chilabothrus striatus exagistus and C. s. warreni ) of the island, whereas the nominate subspecies C. s. striatus occurs in different habitats spread across the whole island.

Haiti became one of the poorest countries in the world from its once flourishing state. Haiti suffers from high degrees of poverty; as a result of this Haiti is largely deforested. The conservation efforts undertaken in the previous years have largely fallen victim to inactivity by the fractured departments within the unstable government. Travel to and within Haiti is considered high risk. The recent earthquake and hurricane tragedies have compounded all of Haiti’s problems. Haiti is one of the most biologically significant but also one of the most environmentally degraded countries in the West Indies. It faces serious conservation and research problems because of its economic situation and political decisions

Curtis recorded the boas in Haiti and found them to be very common in large dead trees, in undisturbed areas but even in local gardens. He also found large boas stretched on branches after rainy nights or in houses pursuing rats. He contradicted Barbours claim that the boa seems to be really uncommon. Curtiss noted that in some places the boa is respected by locals as being the emblem of one of their jinn and many of them keep boas in their homes. He noted that due to his strategy, to buy what islanders brought to his boat, Barbour might have missed to observe the Boas since locals did show their boas seldom to strangers

A study conducted in 1986 to develop a species list for proposed National Parks concluded “species at elevations above 1300 meters are found in Montane Pine Forests/ Cloud Forest; those found below 1300 meters are associated with Wet Forests on limestones. Both of these habitat types provide a cool and humid environment for its inhabitants. Data suggest that when these conditions become more arid through deforestation and agriculture many of the species disappear from the surface with some taking refuge in sinkholes and caves. Other are probably extirpated.”

It is also apparent that certain species are apparently able to thrive under those new conditions and in some cases spread. This has probably enabled certain “weed” species to follow trails where the canopy has been removed into areas that were previously uninhabited by them.”

The fact that Chilabothrus s. striatus can form a viable population as a neozoan on the Puerto Rican island of Vieques

The CIA World Factbook lists the following environmental threats for Haiti: extensive deforestation (much of the remaining forested land is being cleared for agriculture and used as fuel); soil erosion; overpopulation leads to inadequate supplies of potable water and and a lack of sanitation; natural disasters. For the Dominican Republic: water shortages; soil eroding into the sea damages coral reefs; deforestation

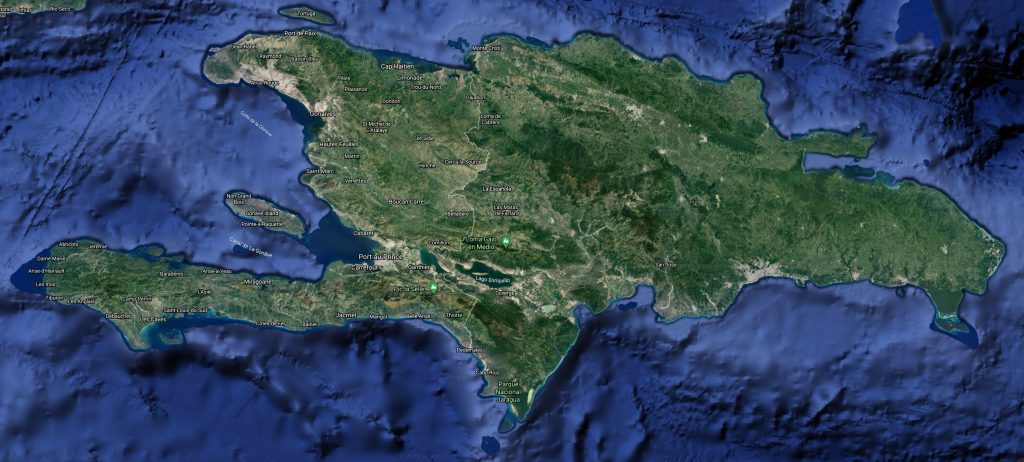

The map below illustrates the extent of habitat destruction and alteration due to development and agriculture. The border between the 2 countries is easily visible by the lack of forest on Haiti’s side.

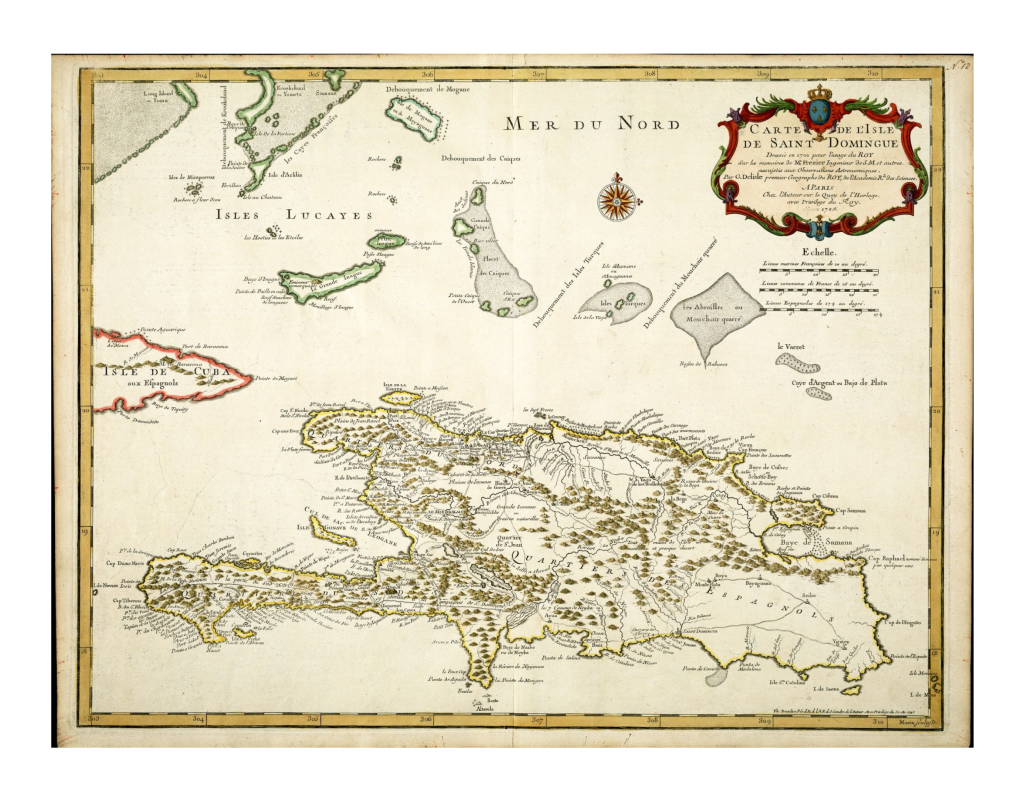

Hispaniola (C.f. fordii, C.f. agametus, C.f. manototus, C.g.gracilis, C.g. hapalus, C. s. striatus, C.s. warreni, C.s. exagistus) Early map of Hispaniola, 1725. Population in captivity A small population of the nominate species, C.s. striatus , is present in the private collections of American and European reptile keepers. We are unaware of any C.s. warreni or C.s. exagistus in any Public Institutions or private collections worldwide.

On display in these Zoos This boa is kept occasionally in zoos, we could find only a few records on here here Chilabothrus striatus.

In the US a pair can be found in the Chicago Zoo, IL.

Handsome Haitians Haitian Boa

Chilabothrus_striatus adult. Picture by Jay Wagner

Haitian Boa

Chilabothrus_striatus adult. Picture by Jay Wagner

Haitian Boa

Chilabothrus_striatus adult. Picture by Jay Wagner

Haitian Boa

Chilabothrus striatus The red color phase of the Haitian Boa is also known as Dominican Red Mountain Boa. Picture by

Jeff Murray

Haitian Boa

Outdoor enclosures for

Chilabothrus striatus in Florida. Picture by

Tom Crutchfield

Haitian Boa

Chilabothrus striatus litter of newborn animals. Picture by

Tom Crutchfield

Anecdotal information Doris M. Cochran wrote, in 1924, of Dr. W.L. Abbott:

Continue to Chilabothrus striatus exagistus

Citations

{2129430:GPMAVE4K};{2129430:WPYXP4KX};{2129430:GPMAVE4K};{2129430:GPMAVE4K};{2129430:3PGW6ASI};{2129430:QQM9K6QS};{2129430:4M2S3VRG};{2129430:B5KXQKJ6};{2129430:FKN8ZAUB};{2129430:LBGADMLZ};{2129430:BYHDXVVG};{2129430:9E8Z6XQ7};{2129430:8597BW5I};{2129430:SFATR6IH};{2129430:X4CDK74G};{2129430:TNMD7KFI};{2129430:458TVYKN};{2129430:TCBYKTNZ};{2129430:HDVKI8LR};{2129430:FTX7PLWT};{2129430:M5C6WETQ};{2129430:FTYCYVBR};{2129430:MRVBSCBF};{2129430:F9XC9DJD};{2129430:WPYXP4KX};{2129430:GMXVACUY};{2129430:AT8W4WR7};{2129430:HR9F33X3};{2129430:MYKEFDQ6};{2129430:MWAJWBEI};{2129430:UUNHHSWB};{2129430:8JQN59AC};{2129430:6QFFGCRZ};{2129430:CWJEARHH};{2129430:6SCYJ9AY};{2129430:YY39B7S9};{2129430:C794F8RH};{2129430:PCLHMKXD};{2129430:TRWL9T99};{2129430:SWS6AK9A};{2129430:AMNVQLZB};{2129430:GPMAVE4K};{2129430:WPYXP4KX};{2129430:WPYXP4KX};{2129430:LBGADMLZ};{2129430:GPMAVE4K};{2129430:WPYXP4KX};{2129430:TNMD7KFI};{2129430:WPYXP4KX};{2129430:WPYXP4KX};{2129430:PLLCED4M};{2129430:YE6WWE9R};{2129430:2HKEJP4F};{2129430:9VXQKNGX};{2129430:WPYXP4KX};{2129430:WPYXP4KX};{2129430:TNMD7KFI};{2129430:D4ATIBKV};{2129430:HR9F33X3};{2129430:WPYXP4KX};{2129430:EDPQZTYK};{2129430:5EHI9MXM};{2129430:BMRNKRE9};{2129430:QHW3LQDU};{2129430:B4PKVBNP};{2129430:X4CDK74G};{2129430:HET54GTL};{2129430:6QFFGCRZ};{2129430:MJRZRYQ5};{2129430:MJRZRYQ5};{2129430:MJRZRYQ5};{2129430:MJRZRYQ5};{2129430:38WM9CUV};{2129430:PA95MFMQ};{2129430:9BIHVIYG};{2129430:8M7APEJU};{2129430:VZUN2NNW};{2129430:FEDC6I9K};{2129430:UUNHHSWB};{2129430:UUNHHSWB};{2129430:9UGISFNT};{2129430:CQY3KLAD};{2129430:TNMD7KFI}

apa

author

asc

no