Scientific Name Corallus cookii

Described and named by John Edward Gray (1800-1875), Keeper of Zoology in the British Museum, in honor of Edward William Cooke, Esq. (1811-1880), a famed maritime painter. Holotype British Museum of Natural History (BMNH) 1946 1.1.50 (formerly BMNH iv.8.1d).

Type Locality Restricted to Saint Vincent, West Indies by Henderson

Subspecies None

Synonyms Corallus Cookii Corallus hortulanus var. melanea Xiphosoma hortulanum Corallus cookii 100 ] [101 ]Corallus cookii 67 ] [68 ] [69 ]Corallus cooki 181 ]Boa cooki 318 ]Boa cooki Corallus cookii Boa hortulana cookii Boa hortulana cookii Boa hortulana Boa hortulana cookii 46 ]Boa hortulana Boa enydris cookii 399 ]Boa hortulana Boa hortulana cookii Boa endris cookii 18 ]Boa hortulana cookii Corallus enydris cookii Corallus hortulanus cookii 62 ]Corallus enydris cookii Corallus enydris cooki Corallus enydris cookii 83 ] [84 ]Corallus enydris cooki Corallus enhydris 36 ] [32 ]Corallus enydris cooki Corallus enydris cooki Corallus enhydris cookii Corallus hortulanus cooki Corallus cooki Corallus cookii Henderson, 1999:Corallus hortulanus Corallus cookii Corallus cooki Tipton, 2005: 42Corallus cookii Treglia, 2006: 260 [261] [262]Corallus cookii Corallus cookii Corallus cookii Corallus cookii Corallus cookii Corallus cookii Corallus cookii Murphy & Crutchfield, 2019: 178Corallus cookii Corallus cookii Corallus cookii Thorpe & Malhotra, 2023: 1-14Common Name Cooke’s Treeboa, Saint Vincent Treeboa.

Description and taxonomic notes A narrow headed, slender bodied boa with a maximum SVL of 1374 mm, ventral scales 257-278, subcaudal scales 100-122, dorsal scale rows 39-48, scales between supraoculars 7-13 (10 modally), circumorbitals 10-14 (12 modally), subloreals 0-4 (2 modally). Dorsally the color is brown, gray or taupe; on rare occasion it is black.

Henderson began his studies of the St. Vincent Treeboas in earnest beginning in 1988. By this time he had visited St. Vincent twice and Granada once. During this period he was able to collect boas at the rate of 6 per hour when in ideal habitat. Some of the boas were caught and preserved for inclusion to the MPM’s collection. Some were captured for captive breeding studies (Henderson, 1988 ).

In a more recent publication Henderson’s sample consisted of 47 boas and concluded the taupe dorsal color was prevalent in 87% of the specimens. The remainder of the specimens examined had a dorsal ground color of gray or brown. He describes the rhomboids as an hourglass or dumbbell shape with the center hollow. The uncommon coloration of black or gray with white reticulations between the patterns is the result of what he suspects is the “serendipitous founder effect.”

One would assume C. cookii to have the same, or similar, color variations of C. grenadensis given its proximity, both physically and genetically, to C. grenadensis and, genetically, to C. hortulanus . Again, Henderson attributes some of the cause as possibly a result of the “serendipitous founder effect.”

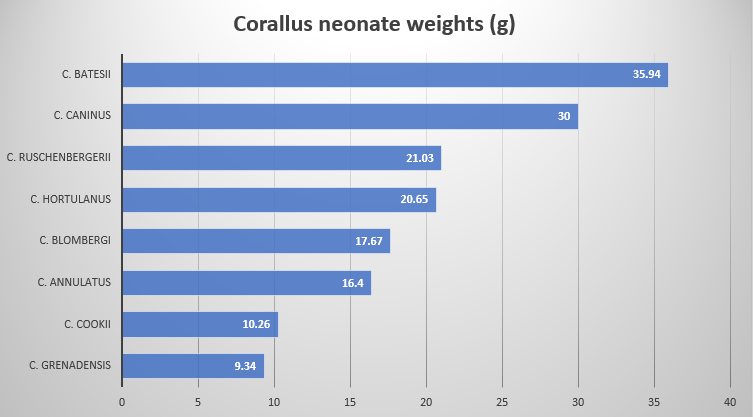

C. cookii (and C. grenadensis) have the shortest and narrowest heads in the genus Corallus. When morphologically plotted, C. Cookii , C. grenadensis , C. ruschenbergerii and C. hortulanus form a cluster due to longer body and tail length with both higher ventral and subcaudal scale counts. C. caninus , C. batesii and C. cropanii form a 2nd cluster, based on their similar morphology. C. annulatus and C. blombergii form a 3rd cluster that sits somewhat equidistant between the other two clusters

An interesting graph depicting the weigths of the Corallus species accessible to the author. Note C. cookii and C. grenadensis are very much smaller and lighter by weight and volume.

Corallus cookii (and Corallus grenadensis ) are nested within Corallus hortulanus. Colston et al (2013) and Reynolds et al (2014), through molecular data, cast doubt on the validity of C. cookii . Colston et al. suggested additional study was needed to determine its true relationship with C. hortulanus

Although C. cookii and C. grenadensis are nested within C. hortulanus C. cookii a valid species using morphological data such as scale count differences, color, pattern and geographic/reproductive isolation.

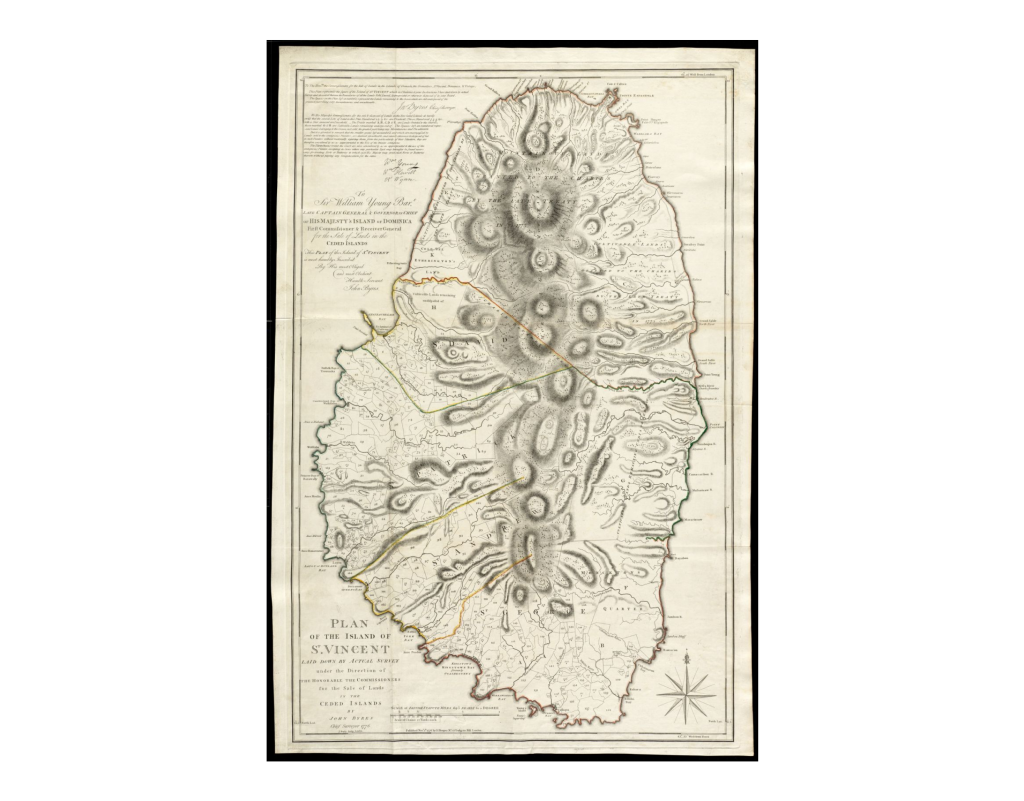

Distribution Saint Vincent. Found from sea level to around 425 meters in elevation

Habitat La Soufriere, a large volcanic cone, rises to about 1220 meters above sea level and dominates Saint Vincent. A deep trough separates it from the central massif and the Morne Garu Mountains. Deep valleys and high steep coastal cliffs comprise the leeward side of the island. On the windward side of the island the valleys are wider and gentler, spreading onto the flat coastal plain. The forest on the island is comprised of young secondary forest, secondary forest, primary forest, plantation forest, palm forest elfin woodland and dry scrub forest

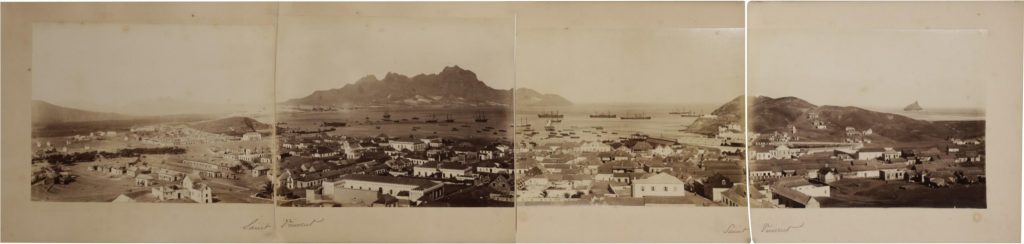

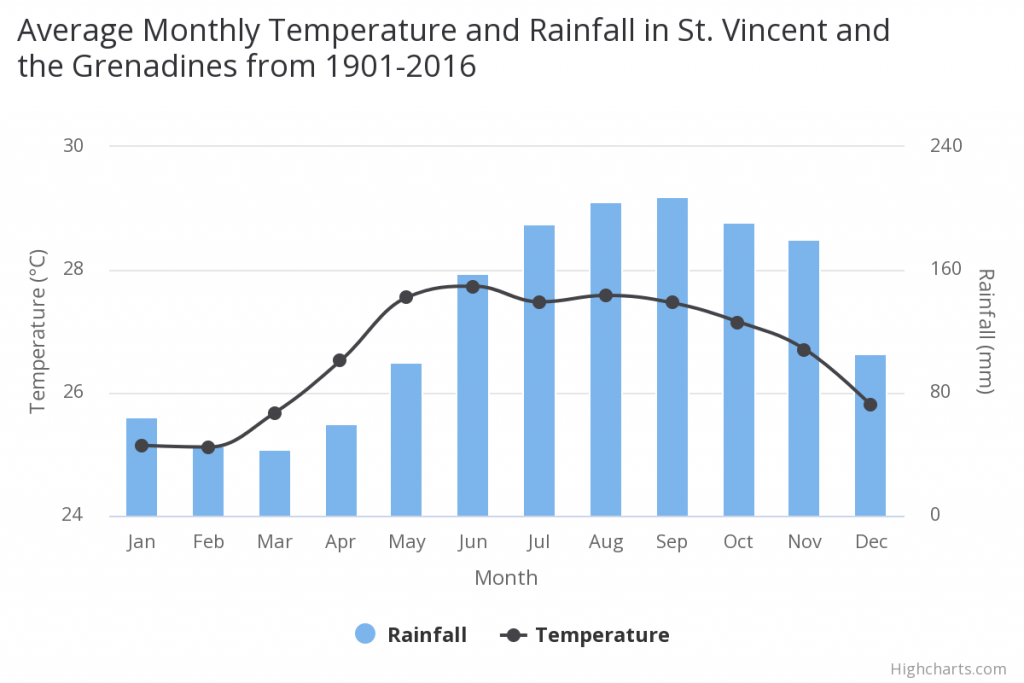

Kingstown, St Vincent from Cane Garden Point. Harris, 1837. On Saint Vincent the mean annual temperature is 26.66°C and the m ean annual precipitation is 1551.50 mm. The valleys and coastal plains receive about 2000 mm and the higher elevations up to 7000 mm. Saint Vincent and the Grenadines have a tropical climate, with hot humid conditions year-round. Historically, the dry season has been from December to May and the rainy season from June to November. However, there have been noticeable changes in this pattern over the last decade: the rainy season now lasts from May to October. The country is impacted by tropical cyclones and hurricanes, as well as the impacts of the El Nino Southern Oscillation. El Nino brings warmer and drier than average conditions between June and August, while La Nina brings colder and wetter conditions during this same time period.

Mean annual temperature has increased by 0.7°C since 1960, at an average rate of 0.16°C per decade and this warming has affected all seasons at a similar rate. Average precipitation has declined by about 8.2 mm per month (-5.7%) per decade over the period 1960-2006. This decline affects all seasons, but is most marked in the wettest seasons during June through November, when the average rate of decline had been 10.6 to 13.5 mm per month (4.9% to 7.1%) per decade.

Powell and Henderson cite gardens, orchards and resorts as suitable habitat the treeboas have exploited as a result of urban sprawl, agriculture and the burgeoning tourism industry. Much of the native flora has been replaced with introduced plants and trees, all to please the eye and palate of the growing tourist population C. cookii has adapted well to human encroachment; as long as there is contiguous tree cover the boas will continue to thrive amongst the urban setting

St. Vincent, ca. 1880. Notice the apparent deforestation as early as this time period. Thankfully, the Treeboas have become adaptable to these habitat changes. Longevity 14 years, 3 months in captivity C. cookii can live as long as its sister species, both in the wild and in captivity.

Reproduction The following reproductive data for C. cookii from zoo and private collections according to Slavens

1965 Ft. Worth, USA. (Boa enydris cookii) 0.0.9 (6 died) (XXXXX, 1967).PPLE bred during 1975.STLM bred during 1975.NEWN 0.0.3 born during 1979.KNOT bred during 1971.GRAC 0.0.20 born Sept 30, 1986.PAIE Bred during 1986.GRAC 0.0.4 born during 1988.PAIE bred during 1988.PPAWa 0.0.9 born 10 Oct 90. Trio put together 1 Jan 90. Light 12 hr. day, 12 hr. night, temperature 78 – 86 degrees F. 9 young born, 434 mm average total length. Adults wild caught.PAIE 0.0.7 born during 1991.PPAWa 0.0.15 born 8 Sep 91. Young were difficult to start on mice or anoles.STLM 0.0.11 born during 1991.

One litter was produced in 2020:

US: 1 live and 5 unfertilized ovum on 29 October. Three litters were produced in 2021:

US: 6 live and 3 unfertilized ovum on 26 September. Smallest neonate weighed 5.51 g and the largest weighed 14 g with an average weight of 11.86 g. US: 5 live, 1 stillborn and 6 unfertilized ovum on 8 October. Smallest neonate weighed 7.96 g and the largest weighed 9.89 g with an average weight of 8.65 g. US: 5 live, 1 stillborn and 2 unfertilized ovum on 8 October. Smallest neonate weighed 7.4 g and the largest weighed 12.0 g with an average of 10.18 g. In the wild mating takes place during the dry season, February and March, and babies are born in the wet months, August and September. In captivity babies are born in Sep/Oct.

Corallus cookii mating at night. Corallus cookii mating. A drop of fluid can be seen on the female’s tail. Murray reports a captive breeding resulting in one live neonate and five unfertilized ova on 29 October, 2020. 55 days later an additional unfertilized ovum was dropped by the female with no apparent ill effect. The neonate was assist fed freshly killed appropriately sized Anolis sagrei for three feedings. It then started voluntarily feeding on hot pink mice covered in chick fuzz for two feedings. It took unscented pink mice after that.

Two neonates from the same litter. Another litter was produced on 26 September, 2021 resulting in six live neonates and three unfertilized ovum. The female ate all three unfertilized ovum; possibly the first documented behavior of this type in the species.

Female C. cookii eating an unfertilized ovum. She ate all three during the night. Litter of six C. cookii born September 26, 2021. Neonate C. cookii after their first shed on 2 November, 2021. The orange coloration will fade over the next 12-18 months. Behavior Nocturnal in nature, arboreal in habit. This boa has adapted well to all the private and commercial activity destroying its native habitat. Henderson refers to it as the “Urban treeboa.” And with good reason; its plasticity in adapting to changing habitats will ensure the boa is around for some time to come. Available food prey for the treeboa is also the result of human encroachment and activities, ensuring there ara numerous and viable food sources for the boas. The treeboa can be found at ground level and as high as 20 meters while foraging for food. Generally, it is found at heights under 5 meters. Like C. grenadensis , it too can be found foraging on the distal ends of branches

Diet C. cookii is one of only two species in the genus whose diet consists mainly of Anolis lizards. While the treeboas of the same size and age on the mainland prey on birds, bats, rodents and marsupials, the island treeboas prey on anoles C. cookii ; juveniles, sub-adults and even adults take them. This could be the result of the lizards being geographically imposed on the boas as a prey item.

The treeboas exist where there are no readily available supplies of rodents. Henderson and Pauers suspect, because lizards are geographically imposed on the boas, they developed a true specialization as a result of the lack of bird and rodent prey. The incredible numbers of Anolis have probably reduced any dependence of young boas on bird prey items and introduced rodents

Of interest is the parallel of the island Chilabothrus and island Corallus -the young of both genus’ have developed a specialization for lizards as juveniles (C. angulifer is the exception). Whereas most of the Chilabothrus quickly outgrow this dependence on lizards (except for C. fordii , C. gracilis and C. granti ), C. cookii feeds on lizards its entire life cycle

Captive management Price lists going back to the 1970’s occasionally offered C. cookii from Saint Vincent. For reasons unknown, by the early 2000’s the boas had all but disappeared from Zoos and hobbyists alike. During that time period the boas were touted as rare. When compared to the other treeboas in the genus, it certainly lacks the color and popularity of its sister taxa.

There are a few private collectors in the EU and US still working with C. cookii , despite its unpopularity. Because the young boas require ectothermic prey as first foods, these boas will never have the appeal of C. hortulanus . Presumably only hobbyists that work with other ectotherm eating prey would have an interest in this species.

Newborn Saint Vincent Treeboa, Corallus cookii Newborn Saint Vincent Treeboa, Corallus cookii Assist feeding a small anole to a 12 day old Corallus cookii. Conservation status, threats and population in the wild CITES: Appendix II

IUCN Red List: None

Catalogue of Life: (click here )

The National Center for Biotechnology Information: (click here )

CITES import/export data: (click here )

The Botanical Garden of St Vincent was established in 1765 and is considered the oldest such site in the Western Hemispehere. In 1791 it was also established as a forest reserve, making it the first Eastern Caribbean island to do so. King’s Hill is thought to be the first legislative order providing for protected areas in the Americas (IUCN 1992). Again in 1912, all land above 1000 feet was designated crown property. Sadly, little protection has been provided or enforced, making the status of the land nothing more than a nod to conservation on paper

1825 diagram of the Botanic Garden St. Vincent. 1825 Botanic Garden from the bottom of the central walk. The topography of Saint Vincent is such that high ground is surrounded by steep slopes; the slopes are paralleled on either side by long cuts filled with extensive vegetation. By 1993 about 38% of land mass had forest cover, of which 5% was primarily mature undisturbed forest. Then, land above 305 meters was set aside to conserve the remaining forest

Using the “paper park” method of conservation, the Wildlife Act of 1987 declared eight areas as wildlife reserves. Additional land was added to the list of wildlife reserves in 2004; thus the list consisted of one national park, three national landmarks and eight forest reserves. Powell and Henderson state this arrangement exists largely on paper; enforcement is difficult and the land in the upper elevations falls into use by the marijuana growers

The current state of Treeboa population numbers, as a result of fieldwork (2006), appears to support the claim Corallus cookii is “remarkably abundant.” It can be found in every habitat up to 500 meters of elevation. As long as there is contiguous vegetation, the boas can thrive. Any deforestation is a threat to this critical habitat need of the boas. The boas can be found in fruit orchards, in built-up areas that have pedestrian and vehicular traffic et al . 2007).

A note about population numbers: habitat destruction and alteration may give the temporary appearance of “remarkably abundant” as geographic crowding takes place. Eventually, overcrowding and lack of adequate food prey items will contribute to increased mortality rates and a decrease in population numbers. The same number of boas, consuming the same prey at the same rate in a now smaller habitat will have the expected deleterious affect. At some point, predators may outnumber prey. This rationale can be loosely applied to other islands and species. For now, though, the boas appear to be in the “comfortable” numbers margin.

Urban sprawl has had a negative effect on snakes; more so than any other reptile group. Nowhere is it more evident than on these small islands. People are still fearful of their native snake fauna and kill them more often than not. With housing and commercial construction trying to keep pace with the ever growing population demands, it is inevitable the treeboas and humans will come in contact with each other. Public education should be a facet of any conservation program to ensure there is one less peril for these unusual and mysterious insular treeboas.

The CIA World Factbook lists the following environmental threats for St. Vincent and the Grenadines: pollution of coastal waters and shorelines from discharges by pleasure yachts and other effluents; in some areas, pollution is severe enough to make swimming prohibitive; poor land use planning; deforestation; watershed management and squatter settlement control

Population in captivity Animals labelled as Cooke’s Treeboa are common in captive collections. However, true Corallus cookii , originating from Saint Vincent are a rare sight. “Garden phase” Corallus hortulanus was especially, and commonly, mislabeled as Cooke’s Treeboas. In recent years a small number of C. cookii (sensu

While the numbers of these animals is by no means large, it can be assumed that sustainable small breeding numbers are ex-situ . Time will tell us how well and often they reproduce. There is no recorded data available on the number of offspring in litters, size and weight of neonates, first food items, etc. We are hopeful that data will be recorded and made available as additional breedings take place.

Old price lists 1971

The maps below are to illustrate the habitat destruction and alteration as a result of development and agriculture.

Saint Vincent and Bank Saint Vincent Early map of Saint Vincent, 1776. On display in these Zoos Due to the confusing nomenclatorical situation associated with the species complex comprised of Corallus hortulanus, C. cookii, C. grenadensis, and C. ruschenbergeri (see Genus Corallus ), it is difficult to conclude if individual animals assigned as Cooke’s Treeboa in public or private collections really represent animals that originated from Saint Vincent. We look forward to receiving any information about the geographic origin of Cooke’s Tree Boas from zoo collections.

Captivating Cooke’s Cook's Tree Boa

Neonates of Cook's Tree Boa, Corallus cookii

Cooks treeboa

Black and white phase neonates of Cook's Tree Boa, Corallus cookii

Cook's Tree Boa

Neonates of Cook's Tree Boa, Corallus cookii

Black and white phase neonates of Cook's Tree Boa, Corallus cooki

Corallus cookii

Young Cooks Tree Boa Corallus cookii prefer lizards a prey. A preference shift for mice takes place after a certain size is reached

Corallus cookii

This Cooks Tree Boa Corallus cookii is one of a few in terraria today

More information: Through the authoritative academic work of Robert W. Henderson as well as others, a wealth of information about the natural history, habitat use and behavior of the Genus Corallus is present. Henderson summarized the current knowledge about the Genus in three books dedicated to the Genus Corallus

Continue to Corallus grenadensis

Citations

{2129430:U4X2CEG2};{2129430:6DFB4S49};{2129430:U4X2CEG2};{2129430:6C2G3SEZ};{2129430:4M2S3VRG};{2129430:B5KXQKJ6};{2129430:FKN8ZAUB};{2129430:SFATR6IH};{2129430:ZABN4Y4X};{2129430:TCBYKTNZ};{2129430:FVPHRUJJ};{2129430:HDVKI8LR};{2129430:FTX7PLWT};{2129430:M5C6WETQ};{2129430:QCU6GFPA};{2129430:XIBSDFES};{2129430:DPV37VVY};{2129430:AT6CPMFB};{2129430:D3MAG6TN};{2129430:F9XC9DJD};{2129430:AT8W4WR7};{2129430:QAC6RZVD};{2129430:MWAJWBEI};{2129430:8JQN59AC};{2129430:6QFFGCRZ};{2129430:CWJEARHH};{2129430:DKHRHI3M};{2129430:6DFB4S49};{2129430:6SCYJ9AY};{2129430:RY37WKW7};{2129430:WATPURAW};{2129430:H249NMQQ};{2129430:TPBGI654};{2129430:TRWL9T99};{2129430:D26RABKF};{2129430:SWS6AK9A};{2129430:AMNVQLZB};{2129430:7KDI4F8I};{2129430:D26RABKF};{2129430:H249NMQQ};{2129430:TPBGI654};{2129430:H249NMQQ};{2129430:D26RABKF};{2129430:6DFB4S49};{2129430:DDF8G6AQ};{2129430:2DW9AMXN};{2129430:B8PSQ5TI};{2129430:EDPQZTYK};{2129430:BMRNKRE9};{2129430:RY37WKW7};{2129430:DAZD4E2P};{2129430:DAZD4E2P};{2129430:S34AAHYL};{2129430:DDF8G6AQ};{2129430:G4GN7PJC};{2129430:YCIPULGJ};{2129430:YCIPULGJ};{2129430:CQY3KLAD};{2129430:6DFB4S49};{2129430:DKHRHI3M},{2129430:RY37WKW7},{2129430:D26RABKF}

apa

author

asc

no