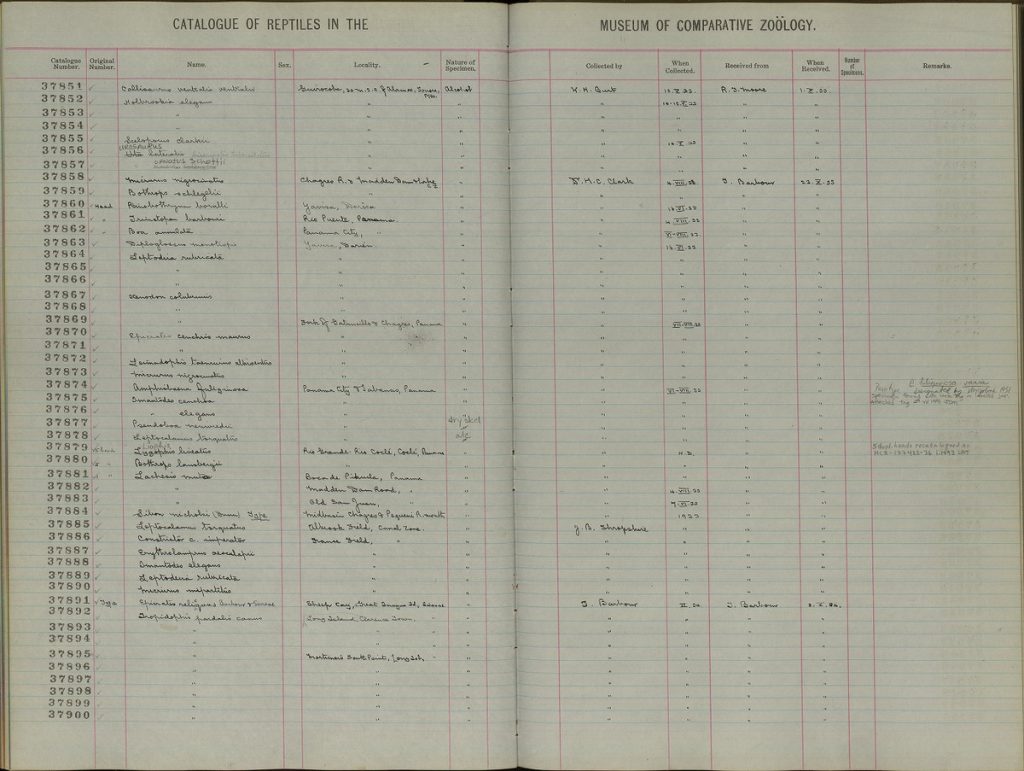

Scientific Name Chilabothrus chrysogaster relicquus C. c. relicquus. Photo Dick Bartlett Described and named by Barbour and Shreve. Dr. Thomas Barbour (1884–1946) was an American zoologist working at the Harvard Museum from 1911 to 1946. In 1927 he was Director and Custodian of the Harvard Biological Station and Botanical Garden, Soledad, Cuba. Benjamin Shreve (1908–1985) was a volunteer herpetologist at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology; he was from a wealthy family of jewelers. Holotype Museum Comparative Zoology no. 37891. Collected by J. Greenway, 1934.

Type Locality Sheep Cay, Great Inagua Island, Bahama Islands.

Synonyms Relicquus is derived from the Latin for "remaining" or "surviving" relic.

Discovery of C.c. relicquus : Greenway and his wife accompanied Barbour on his last voyage aboard Allison Armour's yacht, the Utowana during February, 1934. The first landfall of any consequence was Great Inagua on 25-27 February. Greenway decided to swim to Sheep Cay from the yacht's launch, whereupon he captured a new racer and a new boa. The racer was named Alsophis vudii utowanae and the boa was described and named Chrysogaster c. relicquus by Barbour and Shreve in 1935 (Henderson & Powell 2004).Common Name Southern Bahamas boa.

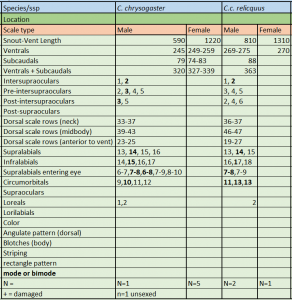

Description and taxonomic remarks Chilabothrus chrysogaster relicquus is characterized by the following combination of characters (N = 3): SVL of 810 mm in males and 1310 mm SVL in the female; high number of ventral scales (269–275) in males and 270 in the female, high number of ventrals + subcaudals (363 in 1 female), high number of dorsal scale rows at midbody (46–47), modally 14 supralabials with 2 entering the eye, modally 17 infralabials, dorsal pattern consisting of a series of angulate dorsal blotches which may be fused to each other or to the prominent ventrolateral series of secondary blotches that extend almost to the dorsal-ventral junction

C.c. relicquus & C.c. chrysogaster meristics. * * Source

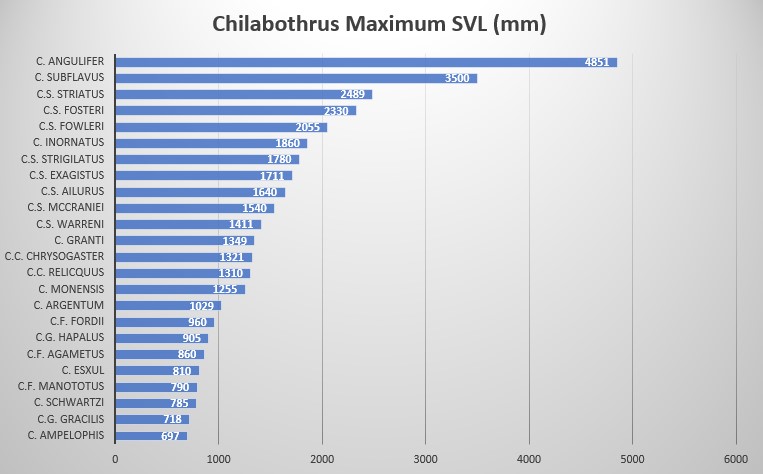

Above: C.c. relicquus entry in the MCZ's catalogue. Photo MCZ In regards to its size, Tolson and Henderson categorized C. chrysogaster as a medium sized member of the genus Chilabothrus (referred to as Epicrates at the time and thus included South American Rainbow Boas) Chilabothrus that are smaller in size and weight (Chilabothrus ampelophis, C. fordii, C. gracilis, C. granti, C. monensis), however, C. c. chrysogaster and C. c. relicquus are by no means large.

Evolution Neither Fossil, nor subfossil remains of Chilabothrus chrysogaster relicquus have been found to date. A study based on molecular data (while not discriminating between the different subspecies) suggests that Chilabothrus chrysogaster is on an isolated evolutionary trajectory for the last 4.1 Million years C. c. relicquus is the closest relative to C. c. chrysogaster . Further genetic studies are required to see if the close chromatological and morphological resemblance between C. c. chrysogaster and C. c. relicquus is reflected on the genetic level or if the relationship is less tight than expected. We are curiously waiting.

Distribution Great Inagua and Sheep Cay, Bahama Islands.

The two subspecies of Chilabothrus chrysogaster occur on different Islands, click on the flags get information Habitat One specimen was found inside of a log in Cocos grove on Great Inagua

The center of the island has a lake somewhat rectangular in circumference, ten by twenty miles, and only three to four feet deep. Within the lake there were hundreds of “islands” of various size, some extremely low and others reaching heights of forty feet. From the shore of the lake to within a few miles of the coast the land consisted of plain or savanna. Very little vegetation grows on the plain, other than a thin growth of buttonwood trees and thatch palm. During rains the lake increases in size, covering much of the savanna making it impassable. It is assumed this regular flooding and receding process has prohibited reptile life on the island

Historically speaking, the Caicos Bank appears to be shoaling. The West Indies Pilot (I: 84) states: There is no doubt that Caicos Bank will, in the course of time, become one island. All evidence points to its constant shoaling. Historical accounts of the pursuits of piratical craft across the bank by naval vessels in the eighteenth and early part of the nineteenth century indicate that even 100 years ago deep channels existed where today a vessel drawing but six feet of water has to proceed with caution….

It is assumed Inagua rose above the sea in much the way of the Caicos Bank. There are recent examples of uplift to support this claim. Five miles east of Polacca Point is a beach now two hundred feet from and fourteen feet above the surface of the sea. On the south coast is Salt Pond Hill, a beach that is quite a distance from the shore

Longevity No data exists regarding the longevity in nature or captivity. We assume the species can live equally long as its closest relative Chilabothrus c. chrysogaster.

Reproduction No data regarding the reproductive biology of this subspecies exists. We assume this taxon has a similar reproductive biology as the nominate subspecies.

Behavior Presumably C. c. relicquus is, like all members of the genus, an active nocturnal forager. Very few observations on the behavior of C. c. relicquus have been made and none have been published.

Diet While the diet of the nominate subspecies has been documented on several accounts, no research or anecdotes have been published for the relicquus subspecies. We assume that C. c. relicquus is similar in it’s dietary habits to C. c. chrysogaster .

Captive management and captive population We assume the relicquus is similar in maintenance requirements as Chilabothrus chrysogaster. Very few of these boas have ever been maintained in captivity and that was 50 or so years ago.

Conservation status, threats and population size in nature CITES: Appendix II

IUCN Red List: None

Catalogue of Life: (click here )

The National Center for Biotechnology Information: (click here)

CITES import/export data: (click here )

In regards to the abundance of Chilabothrus chrysogaster relicquus Buden notes: “Of interest is the apparent rarity of E. chrysogaster on Inagua and the islands of the Crooked-Acklins Bank, which are, for the most part, more mesic than the Turks and Caicos Islands and seemingly more suitable for a population of Epicrates ” Chilabothrus chrysogaster relicquus . Barbour and Shreve thought it to be extinct from Great Inagua as a result of introduced feral animals

Apparently the boas are still on Great Inagua, though difficult to find (Reynolds pers. comm.). However, no research has been published about population densities, population trends, absolute number of snakes on the islands, exact distributional records, ecology, habitat preferences, habitat size and threats. This lack of knowledge makes any conservation initiative a gamble for investing the resources rightfully.

Knowledge from other islands points us to focus on introduced species. Several neozoa are present on Great Inagua. Pigs were introduced in the early 20th century to Great Inagua and are a particular concern in locations where native species are already struggling. Efforts must be made to eliminate or reduce population sizes whenever possible Rattus rattus is commonly found on islands and cays throughout the West Indies. Buden wrote in 1974 “I have seen presumptive R. rattus even on the most bleak and barren islets of the Turks and Caicos banks, where the species is able to subsist under extreme xeric conditions apparently without benefit of resources provided by humans.”

In an overview article over the Conservation of the Bahamian herpetofauna, Knapp et al. considered the major threats to be inappropriate development, apathy, over-exploitation of wildlife, lack of law enforcement, hurricanes, introduced species, and disturbance by tourist activities

Given the level and pace of development in support of the tourism industry and personal residences on the islands and cays, the future outlook for these boas, and everywhere else in the Caribbean, is cause for great concern. As habitat loss increases and prey availability is affected, these boas appear extinction bound. When coupled with introduced feral animals that prey upon the boas, compete for their prey resources and the increasing frequency of natural disasters, scientists must complete their research projects while they can.

Interestingly Knapp et al . didn’t list human caused climate change as a particular threat. Considering that their article was written a decade ago, this might seem understandable. The tables have turned rapidly and and climate is changing as we write these sentences. Thus, we see climate change as the biggest threat, since it will alter the habitats of C. c. relicquus and other species in unprecedented ways over a very short time span.

The non-existence of a captive population prevents attempts for ex situ conservation. We would therefore praise any concerted approach that involves collaboration between in situ conservation and breeding programs, academic research and ex situ breeding programs. We are open for collaboration to any measure that ensures species survival in situ and ex situ. How long can these beautiful and wonderfully unique boas continue their tenuous grasp on life in the West Indies? We know no more about this boa than when it was described 80+ years ago. We consider this subspecies a prime candidate for the Invisible Ark.

The CIA World Factbook lists the following environmental threats for The Bahamas: coral reef decay; solid waste disposal

The maps below illustrate the extent of habitat destruction and alteration due to development and agriculture.

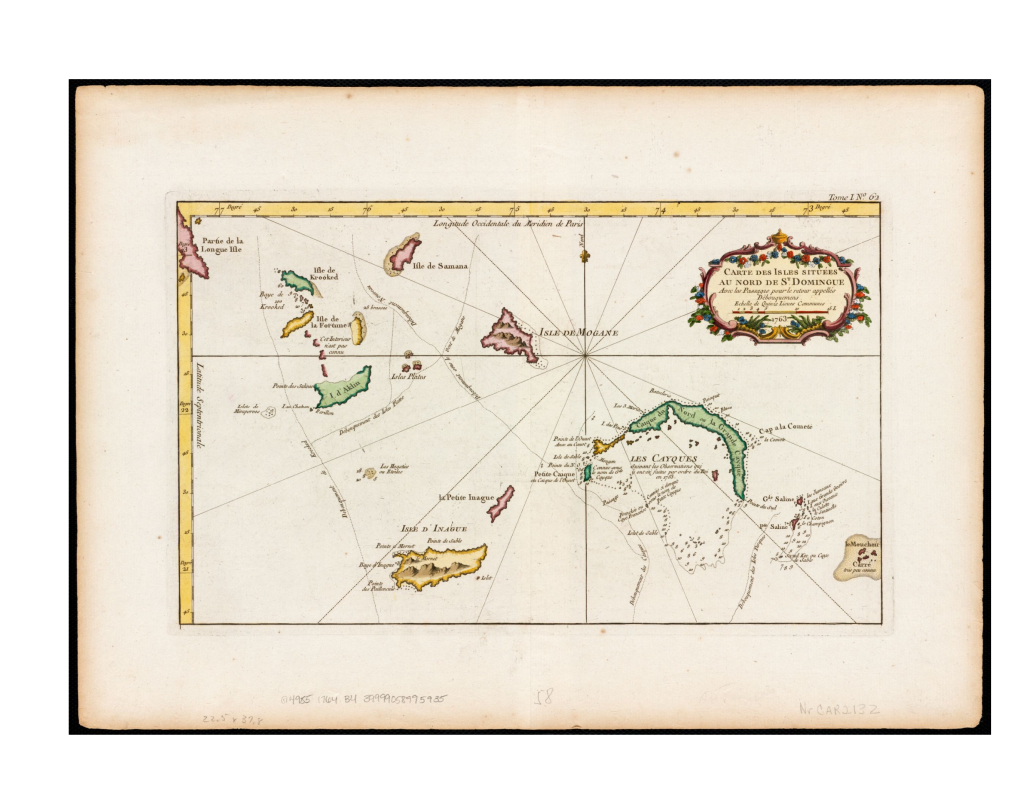

Great Inagua (C.c. relicquus) Little Inagua (C.c. relicquus) Early map of the Turks/Caicos Bank, 1764. On display in these Zoos Currently we are unaware of any live Chilabothrus chrysogaster in Zoo or academic collections anywhere in the world. If you have further information, please notify us .

Further photographs of the Southern Bahamas Boa Chilabothrus chrysogaster relicquus Great Inagua Island, Picture by Joseph Burgess

Continue to Chilabothrus exsul

Citations

{2129430:JFVRARVB};{2129430:JFVRARVB};{2129430:HDVKI8LR};{2129430:M5C6WETQ};{2129430:FTYCYVBR};{2129430:R4DFLTWC};{2129430:F9XC9DJD};{2129430:WPYXP4KX};{2129430:GMXVACUY};{2129430:AT8W4WR7};{2129430:MWAJWBEI};{2129430:8JQN59AC};{2129430:CWJEARHH};{2129430:YY39B7S9};{2129430:SWS6AK9A};{2129430:84STGQRA};{2129430:AMNVQLZB};{2129430:WPYXP4KX};{2129430:WPYXP4KX};{2129430:QHW3LQDU};{2129430:9VXQKNGX};{2129430:6QFFGCRZ};{2129430:XZRL5L5M};{2129430:XZRL5L5M};{2129430:XZRL5L5M};{2129430:8HYDNERM};{2129430:JFVRARVB};{2129430:8HYDNERM};{2129430:STXAUQSV};{2129430:7AZD7R7E};{2129430:5NI8M4CY};{2129430:STXAUQSV};{2129430:CQY3KLAD}

apa

author

asc

no

11543 %7B%22status%22%3A%22success%22%2C%22updateneeded%22%3Afalse%2C%22instance%22%3A%22zotpress-b8ce7b86f3eddc4f94977055a1c2cbbe%22%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22request_last%22%3A0%2C%22request_next%22%3A0%2C%22used_cache%22%3Atrue%7D%2C%22data%22%3A%5B%7B%22key%22%3A%22M5C6WETQ%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Barbour%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221937%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EBarbour%2C%20T.%20%281937%29.%20Third%20list%20of%20Antillean%20reptiles%20and%20amphibians.%20%3Ci%3EBulletin%20of%20the%20Museum%20of%20Comparative%20Zoology%20at%20Harvard%20College.%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E82%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%2077%26%23x2013%3B166.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.biodiversitylibrary.org%5C%2Fpart%5C%2F14803%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.biodiversitylibrary.org%5C%2Fpart%5C%2F14803%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Third%20list%20of%20Antillean%20reptiles%20and%20amphibians%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Thomas%2C%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Barbour%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221937%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220027-4100%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.biodiversitylibrary.org%5C%2Fpart%5C%2F14803%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-10-25T10%3A33%3A36Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22HDVKI8LR%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Barbour%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221935%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EBarbour%2C%20T.%20%281935%29.%20A%20second%20list%20of%20Antillean%20reptiles%20and%20amphibians.%20%3Ci%3EZoologica%26%23x202F%3B%3A%20Scientific%20Contributions%20of%20the%20New%20York%20Zoological%20Society.%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E19%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%283%29%2C%2077%26%23x2013%3B141.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.biodiversitylibrary.org%5C%2Fpart%5C%2F203717%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.biodiversitylibrary.org%5C%2Fpart%5C%2F203717%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22A%20second%20list%20of%20Antillean%20reptiles%20and%20amphibians%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Thomas%2C%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Barbour%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221935%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220044-507X%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.biodiversitylibrary.org%5C%2Fpart%5C%2F203717%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-10-26T17%3A38%3A55Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22R4DFLTWC%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Barbour%20and%20Loveridge%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221946%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EBarbour%2C%20T.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Loveridge%2C%20A.%20%281946%29.%20First%20supplement%20to%20Typical%20reptiles%20and%20amphibians.%20%3Ci%3EBulletin%20of%20the%20Museum%20of%20Comparative%20Zoology%20at%20Harvard%20College.%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E96%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%2059%26%23x2013%3B214.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.biodiversitylibrary.org%5C%2Fpart%5C%2F12098%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.biodiversitylibrary.org%5C%2Fpart%5C%2F12098%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22First%20supplement%20to%20Typical%20reptiles%20and%20amphibians%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22T%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Barbour%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Arthur%2C%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Loveridge%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221946%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220027-4100%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.biodiversitylibrary.org%5C%2Fpart%5C%2F12098%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-11-10T11%3A23%3A18Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22JFVRARVB%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Barbour%20and%20Shreve%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221935%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A2%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EBarbour%2C%20T.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Shreve%2C%20B.%20%281935%29.%20Concerning%20Some%20Bahamian%20Reptiles%20with%20Notes%20on%20the%20Fauna.%20%3Ci%3EProceedings%20of%20the%20Boston%20Society%20of%20Natural%20History%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E40%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%285%29%2C%20347%26%23x2013%3B366.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Concerning%20Some%20Bahamian%20Reptiles%20with%20Notes%20on%20the%20Fauna%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Thomas%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Barbour%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22B.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Shreve%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221935%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-09-18T08%3A26%3A07Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%227AZD7R7E%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Borroto-P%5Cu00e1ez%20and%20Woods%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222012%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EBorroto-P%26%23xE1%3Bez%2C%20R.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Woods%2C%20C.%20A.%20%282012%29.%20STATUS%20AND%20IMPACT%20OF%20INTRODUCED%20MAMMALS%20IN%20THE%20WEST%20INDIES.%20In%20%3Ci%3ETerrestrial%20Mammals%20of%20the%20West%20Indies%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%20%28pp.%20241%26%23x2013%3B257%29.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22bookSection%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22STATUS%20AND%20IMPACT%20OF%20INTRODUCED%20MAMMALS%20IN%20THE%20WEST%20INDIES%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Rafael%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Borroto-P%5Cu00e1ez%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Charles%20A%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Woods%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22The%20mammals%20introduced%20to%20the%20West%20Indies%20have%20had%20a%20negative%20impact%20on%20the%20endemic%20fauna.%20Rats%2C%20mongooses%2C%20cats%2C%20dogs%2C%20among%20others%2C%20jeopardize%20the%20conservation%20of%20Cuban%20and%20Hispaniolan%20solenodons%2C%20capromyid%20rodents%20and%20many%20species%20of%20birds%2C%20reptiles%2C%20amphibians%20and%20invertebrates.%20The%20current%20status%20of%20introduced%20mammals%20in%20the%20Antilles%20along%20with%20their%20impact%2C%20type%20of%20introduction%2C%20field%20observations%20and%20distribution%20is%20summarized.%20Forty%20species%20have%20been%20introduced%20to%20153%20islands.%20Black%20and%20brown%20rats%20as%20well%20as%20mice%20are%20now%20reported%20on%20123%2C%2024%20and%2045%20islands%20and%20keys%20respectively.%20Cats%2C%20mongoose%2C%20and%20dogs%20are%20found%20in%2048%2C%2040%20and%2043%20islands%20respectively%2C%20and%20goats%20on%2032%20insular%20territories.%20Their%20widespread%20distribution%20justifies%20the%20crucial%20establishment%20of%20a%20management%20policy%20on%20invasive%20species%20for%20the%20conservation%20of%20the%20West%20Indian%20fauna.%22%2C%22bookTitle%22%3A%22Terrestrial%20Mammals%20of%20the%20West%20Indies%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222012%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-11-11T16%3A05%3A02Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22YY39B7S9%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Buckner%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222012%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EBuckner%2C%20S.%20D.%2C%20Franz%2C%20R.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Reynolds%2C%20R.%20G.%20%282012%29.%20BAHAMA%20ISLANDS%20AND%20TURKS%20%26amp%3B%20CAICOS%20ISLANDS.%20In%20%3Ci%3EIsland%20lists%20of%20West%20Indian%20amphibians%20and%20reptiles%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%20%28Vol.%202%2C%20pp.%2093%26%23x2013%3B110%29.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22bookSection%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22BAHAMA%20ISLANDS%20AND%20TURKS%20%26%20CAICOS%20ISLANDS%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Sandra%20D.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Buckner%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Richard%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Franz%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22R.%20Graham%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Reynolds%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22The%20Bahamian%20Archipelago%20lies%20in%20the%20North%20Atlan-tic%2C%20southeast%20of%20Florida%20and%20north%20of%20Cuba%20and%20Hispaniola%20%28Fig.%203%29.%20The%20area%20consists%20of%20more%20than%202%2C700%20oceanic%20islands%2C%20cays%20%28pronounced%20%5Cu201ckeys%5Cu201d%29%2C%20and%20rocks%20that%20are%20dispersed%20among%2015%20shallow-water%20carbonate%20banks.%20Mouchoir%2C%20Silver%2C%20and%20Navidad%20banks%20in%20the%20eastern%20Turks%20and%20Caicos%20area%20are%20completely%20inundated.%20The%20banks%20are%20separated%20by%20deep-water%20trenches%20and%20strong%20ocean%20currents.%20These%20banks%20and%20their%20associated%20islands%20extend%20between%20latitudes%2020%5Cu00baN%20and%2028%5Cu00baN%20and%20longitudes%2071%5Cu00baW%20and%2080%5Cu00baW.%20All%20of%20the%20banks%20are%20flooded%20with%20marine%20waters.%20The%20combined%20island%20land%20mass%20associated%20with%20this%20immense%20area%20comprises%20only%20about%2011%2C000%20km2%22%2C%22bookTitle%22%3A%22Island%20lists%20of%20West%20Indian%20amphibians%20and%20reptiles%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222012%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-07-19T18%3A57%3A12Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%228HYDNERM%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Buden%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221975%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EBuden%2C%20D.%20W.%20%281975%29.%20Notes%20on%20Epirates%20chrysogaster%20%28Serpentes%3A%20Boide%29%20with%20the%20description%20of%20a%20new%20subspecies.%20%3Ci%3EHerpetologica%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E31%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%282%29%2C%20166%26%23x2013%3B177.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Notes%20on%20Epirates%20chrysogaster%20%28Serpentes%3A%20Boide%29%20with%20the%20description%20of%20a%20new%20subspecies%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Donald%20W.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Buden%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Data%20on%20morphological%20variation%20and%20distribution%20of%20the%20boid%20snake%20Epicrates%20chrysogaster%20are%20presented%2C%20along%20with%20notes%20on%20littermates%2C%20born%20in%20captivity%2C%20and%20a%20description%20of%20a%20new%20subspecies%20E.%20ch.%20schwartzi.%20Comparisons%20are%20drawn%20between%20E.%20chrysogaster%20and%20other%20faunal%20and%20floral%20elements%20with%20reference%20to%20patterns%20of%20distribution%20and%20degrees%20of%20differentiationin%20the%20southern%20Bahamas.%20E.%20chrysogaster%20is%20interpreted%20to%20be%20most%20closely%20related%20to%20E.%20striatus%20of%20Hispaniola%20and%20the%20northern%20Bahamas.%20The%20distictiveness%20of%20E.%20chrysogaster%20suggests%20a%20long%20period%20of%20isolation%20from%20its%20ancestors%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221975%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22English%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-03-11T09%3A41%3A49Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%225NI8M4CY%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Buden%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221974%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EBuden%2C%20D.%20W.%20%281974%29.%20PREY%20REMAINS%20OF%20BARN%20OWLS%20IN%20THE%20SOUTHERN%20BAHAMA%20ISLANDS.%20%3Ci%3ETHE%20WILSON%20BULLETIN%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E86%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%284%29%2C%20336%26%23x2013%3B343.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22PREY%20REMAINS%20OF%20BARN%20OWLS%20IN%20THE%20SOUTHERN%20BAHAMA%20ISLANDS%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Donald%20W%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Buden%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221974%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222021-01-14T22%3A08%3A09Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22CQY3KLAD%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Central%20Intelligence%20Agency%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222021%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3ECentral%20Intelligence%20Agency.%20%282021%29.%20%3Ci%3EThe%20World%20Factbook%3C%5C%2Fi%3E.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.cia.gov%5C%2Fthe-world-factbook%5C%2F%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.cia.gov%5C%2Fthe-world-factbook%5C%2F%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22The%20World%20Factbook%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Central%20Intelligence%20Agency%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222021%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.cia.gov%5C%2Fthe-world-factbook%5C%2F%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222021-01-18T12%3A00%3A32Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%2284STGQRA%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Currie%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222019%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3ECurrie%2C%20D.%2C%20Wunderle%2C%20J.%20M.%2C%20Freid%2C%20E.%2C%20Ewert%2C%20D.%20N.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Lodge%2C%20D.%20J.%20%282019%29.%20%3Ci%3EThe%20natural%20history%20of%20the%20Bahamas%3A%20a%20field%20guide%3C%5C%2Fi%3E.%20Comstock%20Publishing%20Associates%2C%20an%20imprint%20of%20Cornell%20University%20Press.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22The%20natural%20history%20of%20the%20Bahamas%3A%20a%20field%20guide%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Dave%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Currie%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Joseph%20M.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Wunderle%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Ethan%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Freid%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22David%20N.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Ewert%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Deborah%20Jean%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Lodge%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%5C%22Includes%20color%20photos%20and%20descriptions%20of%20the%20terrestrial%20flora%20and%20fauna%20commonly%20observed%20in%20the%20Bahamas%20archipelago%20and%20provides%20a%20brief%20summary%20of%20the%20geology%2C%20history%2C%20climate%20and%20weather%2C%20important%20habitats%2C%20role%20of%20humans%20in%20habitat%20disturbance%2C%20and%20conservation%20issues.%20Written%20for%20a%20general%20audience%5C%22--Provided%20by%20publisher%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222019%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22978-1-5017-3802-9%20978-1-5017-3803-6%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222021-02-24T20%3A37%3A43Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22AMNVQLZB%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Hedges%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222019-05-28%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EHedges%2C%20S.%20B.%2C%20Powell%2C%20R.%2C%20Henderson%2C%20R.%20W.%2C%20Hanson%2C%20S.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Murphy%2C%20J.%20C.%20%282019%29.%20Definition%20of%20the%20Caribbean%20Islands%20biogeographic%20region%2C%20with%20checklist%20and%20recommendations%20for%20standardized%20common%20names%20of%20amphibians%20and%20reptiles.%20%3Ci%3ECaribbean%20Herpetology%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%201%26%23x2013%3B53.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.31611%5C%2Fch.67%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.31611%5C%2Fch.67%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Definition%20of%20the%20Caribbean%20Islands%20biogeographic%20region%2C%20with%20checklist%20and%20recommendations%20for%20standardized%20common%20names%20of%20amphibians%20and%20reptiles%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22S.%20Blair%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Hedges%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Robert%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Powell%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Robert%20W.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Henderson%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Sarah%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Hanson%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22John%20C.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Murphy%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22To%20facilitate%20biological%20study%20we%20define%20%5Cu201cCaribbean%20Islands%5Cu201d%20as%20a%20biogeographic%20region%20that%20includes%20the%20Antilles%2C%20the%20Bahamas%2C%20and%20islands%20bordering%20Central%20and%20South%20America%20separated%20from%20mainland%20areas%20by%20at%20least%2020%20meters%20of%20water%20depth.%20The%20advantages%20of%20this%20definition%20are%20that%20it%20captures%20nearly%20all%20islands%20with%20endemic%20species%20and%20with%20at%20least%20some%20Antillean-derived%20species%2C%20and%20still%20circumscribes%20a%20region%20of%20high%20biodiversity%20and%20biogeographic%20significance.%20We%20argue%20that%20Caribbean%20islands%2C%20in%20this%20expanded%20sense%2C%20are%20also%20cohesive%20from%20a%20conservation%20standpoint%20in%20that%20they%20share%20high%20human%20population%20densities%20and%20similar%20conservation%20threats.%20A%20disadvantage%20of%20this%20definition%2C%20strictly%20applied%2C%20is%20that%20it%20includes%20some%20islands%20%28e.g.%2C%20Trinidad%29%20that%20have%20mostly%20mainland%20species.%20However%2C%20we%20propose%20that%20researchers%20can%20increase%20the%20stringency%20of%20the%20definition%20so%20that%20it%20is%20less%20inclusive%2C%20and%20make%20comparisons%20between%20different%20definitions%20as%20needed.%20We%20provide%20an%20updated%20checklist%20with%20standardized%20common%20English%20names%20for%20the%201%2C013%20species%20of%20amphibians%20and%20reptiles%20occurring%20in%20the%20region%2C%20along%20with%20principles%20for%20constructing%20common%20names.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222019-5-28%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.31611%5C%2Fch.67%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%222333-2468%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.caribbeanherpetology.org%5C%2Fpdfs%5C%2Fch67.pdf%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-09-13T23%3A10%3A49Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22STXAUQSV%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Knapp%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222011-04-07%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EKnapp%2C%20C.%20R.%2C%20Iverson%2C%20J.%20B.%2C%20Buckner%2C%20S.%20D.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Cant%2C%20S.%20V.%20%282011%29.%20Conservation%20Of%20Amphibians%20And%20Reptiles%20In%20The%20Bahamas.%20In%20J.%20Horrocks%2C%20B.%20Wilson%2C%20%26amp%3B%20A.%20Hailey%20%28Eds.%29%2C%20%3Ci%3EConservation%20of%20Caribbean%20Island%20Herpetofaunas%20Volume%202%3A%20Regional%20Accounts%20of%20the%20West%20Indies%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%20%28pp.%2053%26%23x2013%3B88%29.%20Brill.%20https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1163%5C%2Fej.9789004194083.i-439.21%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22bookSection%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Conservation%20Of%20Amphibians%20And%20Reptiles%20In%20The%20Bahamas%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Charles%20R.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Knapp%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22John%20B.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Iverson%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Sandra%20D.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Buckner%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Shelley%20V.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Cant%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22editor%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Julia%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Horrocks%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22editor%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Byron%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Wilson%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22editor%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Adrian%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Hailey%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22The%20Bahamas%20are%20unique%20relative%20to%20other%20countries%20and%20dependent%20territories%20in%20the%20West%20Indies%20because%20they%20comprise%2029%20islands%2C%20hundreds%20of%20cays%2C%20and%20thousands%20of%20emergent%20rocks%20spread%20over%20215%2C000%20km2%20of%20ocean.%20The%20native%20herpetofauna%20of%20The%20Bahamas%20is%20derived%20primarily%20from%20Cuba%20and%20Hispaniola%2C%20and%20numbers%2046%20species%20comprised%20of%20three%20frogs%20%28including%20one%20endemic%29%2C%2025%20lizards%20%2813%20endemic%29%2C%2011%20snakes%20%287%20endemic%29%2C%20two%20freshwater%20turtles%2C%20and%20%5Cufb01ve%20sea%20turtles.%20Of%20the%20native%20terrestrial%20species%2C%2085%25%20are%20either%20not%20assessed%20or%20data%20de%5Cufb01cient%20to%20af%5Cufb01rm%20IUCN%20listing%2C%20thus%20stressing%20the%20need%20for%20more%20research%20in%20The%20Bahamas.%20Currently%2C%20there%20are%20few%20legislative%20laws%20directly%20protecting%20the%20herpetofauna%20of%20The%20Bahamas%20although%20all%20three%20rock%20iguanas%20%28Cyclura%29%20are%20technically%20given%20full%20protection%20under%20the%20Wild%20Animals%20%28Protection%29%20Act%20of%201968.%20In%202009%2C%20the%20Bahamian%20Ministry%20of%20Agriculture%20and%20Marine%20Resources%20amended%20the%20Fisheries%20Regulations%20governing%20marine%20turtles%20in%20order%20to%20give%20full%20protection%20to%20all%20sea%20turtles%20found%20in%20its%20waters.%20Other%20species%20are%20afforded%20protection%20in%20a%20fairly%20extensive%20system%20of%2025%20national%20parks%2C%20though%20threats%20from%20various%20fronts%20hinder%20safeguarding%20all%20species.%20Major%20threats%20to%20the%20Bahamian%20herpetofauna%20include%20inappropriate%20development%2C%20apathy%2C%20over-exploitation%20of%20wildlife%2C%20lack%20of%20law%20enforcement%2C%20hurricanes%2C%20introduced%20species%2C%20and%20disturbance%20by%20tourist%20activities.%20We%20explore%20the%20challenges%20for%20long-term%20conservation%20of%20the%20Bahamian%20herpetofauna%20and%20provide%20suggestions%20to%20help%20mitigate%20pressures%20on%20amphibian%20and%20reptile%20populations.%22%2C%22bookTitle%22%3A%22Conservation%20of%20Caribbean%20Island%20Herpetofaunas%20Volume%202%3A%20Regional%20Accounts%20of%20the%20West%20Indies%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222011-04-07%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22978-90-04-19408-3%20978-90-04-19409-0%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fbooksandjournals.brillonline.com%5C%2Fcontent%5C%2Fbooks%5C%2F10.1163%5C%2Fej.9789004194083.i-439.21%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-08-20T09%3A33%3A36Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22AT8W4WR7%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Maclean%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221977%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EMaclean%2C%20W.%20P.%2C%20Kellner%2C%20R.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Dennis%2C%20H.%20%281977%29.%20Island%20lists%20of%20West%20Indian%20amphibians%20and%20reptiles.%20%3Ci%3ESmithsonian%20Herpetological%20Information%20Service%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E40%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%201%26%23x2013%3B47.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.5479%5C%2Fsi.23317515.40.1%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.5479%5C%2Fsi.23317515.40.1%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Island%20lists%20of%20West%20Indian%20amphibians%20and%20reptiles%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22W.%20P.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Maclean%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22R.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Kellner%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22H.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Dennis%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221977%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.5479%5C%2Fsi.23317515.40.1%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%2223317515%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Frepository.si.edu%5C%2Fhandle%5C%2F10088%5C%2F9910%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-03-16T23%3A07%3A37Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22FTYCYVBR%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Mertens%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221939%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EMertens%2C%20Robert.%20%281939%29.%20%3Ci%3EHerpetologische%20Ergebnisse%20einer%20Reise%20nach%20der%20Insel%20Hispaniola%2C%20Westindien.%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%20Vittorio%20Klostermann%3B%20%5C%2Fz-wcorg%5C%2F.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Herpetologische%20Ergebnisse%20einer%20Reise%20nach%20der%20Insel%20Hispaniola%2C%20Westindien.%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Robert.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Mertens%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221939%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22German%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-08-02T21%3A05%3A09Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22XZRL5L5M%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Noble%20and%20Klingel%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221932%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A2%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3ENoble%2C%20G.%20K.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Klingel%2C%20G.%20C.%20%281932%29.%20%3Ci%3EThe%20reptiles%20of%20Great%20Inagua%20Island%2C%20British%20West%20Indies%3C%5C%2Fi%3E.%20American%20Museum%20of%20Natural%20History%3B%20%5C%2Fz-wcorg%5C%2F.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22The%20reptiles%20of%20Great%20Inagua%20Island%2C%20British%20West%20Indies%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22G.%20Kingsley%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Noble%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Gilbert%20C.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Klingel%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22While%20on%20a%20cruise%20through%20the%20West%20Indies%20in%20the%20interests%20of%20the%5CnAmerican%20Museum%20and%20of%20the%20Natural%20History%20Society%20of%20Maryland%2C%5Cnthe%20yawl%20%27Basilisk%27%20was%20wrecked%20on%20Great%20Inagua%20Island%20in%20the%20southern%5CnBahamas.%20Mr.%20G.%20C.%20Klingel%20remained%20there%20from%20December%2010%2C%5Cn1930%20to%20March%2011%2C%201931%2C%20and%20devoted%20considerable%20time%20to%20collecting%20and%5Cnstudying%20the%20reptiles%20of%20the%20island.%20Mr.%20W.%20W.%20Coleman%2C%20the%20other%5Cnmember%20of%20the%20expedition%2C%20helped%20greatly%20with%20the%20work%20but%20was%20obliged%5Cnto%20return%20home%20on%20January%2013%2C%201931.%20A%20brief%20account%20of%20the%20work%2C%5Cntogether%20with%20some%20illustration%20of%20the%20lizards%20and%20a%20few%20of%20the%20habitats%2C%5Cnhas%20already%20been%20published%20%28Klingel%2C%201932%29.%20Although%201734%20specimens%5Cnof%20reptiles%20were%20collected%2C%20these%20include%20only%20six%20species%20and%20one%20subspecies.%5CnWe%20believe%20this%20small%20number%20is%20a%20complete%20representation%20of%20all%5Cnthe%20species%20of%20reptiles%20to%20be%20found%20on%20the%20island%2C%20exclusive%20of%20the%20sea%5Cnturtles.%20No%20Amphibia%20were%20secured%20in%20spite%20of%20diligent%20search%20during%5Cnboth%20the%20day%20and%20the%20evening%2C%20as%20well%20as%20after%20rains.%5CnGreat%20Inagua%20is%20about%20forty-five%20miles%20in%20greatest%20length%20and%20eighteen%5Cnin%20width.%20Its%20reptilian%20fauna%20is%20poorer%20in%20species%20than%20that%20of%20many%5CnBahaman%20islands%20of%20much%20smaller%20size%2C%20such%20as%20New%20Providence%2C%20for%5Cnexample.%20In%20attempting%20to%20account%20for%20the%20poverty%20of%20reptile%20life%20on%5CnGreat%20Inagua%20we%20have%20examined%20both%20the%20ecological%20conditions%20on%20the%5Cnisland%20and%20the%20relationships%20of%20the%20species%20found%20there.%20Two%20species%5Cnand%20one%20race%20are%20reported%20below%20as%20new.%20One%20of%20these%20species%20is%20so%5Cnmarkedly%20different%20from%20AristeUiger%2C%20to%20which%20apparently%20it%20is%20most%5Cnclosely%20allied%2C%20that%20it%20is%20referred%20to%20a%20new%20genus.%20The%20degree%20of%20endemism%5Cnon%20Great%20Inagua%20is%20exceedingly%20high.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221932%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22English%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-09-02T21%3A28%3A44Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22SWS6AK9A%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Reynolds%20and%20Henderson%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222018%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EReynolds%2C%20R.%20G.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Henderson%2C%20R.%20W.%20%282018%29.%20Boas%20of%20the%20World%20%28Superfamily%20Booidae%29%3A%20A%20Checklist%20With%20Systematic%2C%20Taxonomic%2C%20and%20Conservation%20Assessments.%20%3Ci%3EBulletin%20of%20the%20Museum%20of%20Comparative%20Zoology%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E162%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%281%29%2C%201%26%23x2013%3B58.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.3099%5C%2FMCZ48.1%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.3099%5C%2FMCZ48.1%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Boas%20of%20the%20World%20%28Superfamily%20Booidae%29%3A%20A%20Checklist%20With%20Systematic%2C%20Taxonomic%2C%20and%20Conservation%20Assessments%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22R.%20Graham%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Reynolds%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Robert%20W.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Henderson%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%2209%5C%2F2018%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.3099%5C%2FMCZ48.1%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220027-4100%2C%201938-2987%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.bioone.org%5C%2Fdoi%5C%2F10.3099%5C%2FMCZ48.1%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-09-03T22%3A37%3A45Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%229VXQKNGX%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Reynolds%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222018%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EReynolds%2C%20R.%20G.%2C%20Puente-Rol%26%23xF3%3Bn%2C%20A.%20R.%2C%20Burgess%2C%20J.%20P.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Baker%2C%20B.%20O.%20%282018%29.%20Rediscovery%20and%20a%20Redescription%20of%20the%20Crooked-Acklins%20Boa%2C%20%3Ci%3EChilabothrus%20schwartzi%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%20%28Buden%2C%201975%29%2C%20Comb.%20Nov.%20%3Ci%3EBreviora%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E558%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%281%29%2C%201%26%23x2013%3B16.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.3099%5C%2FMCZ46.1%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.3099%5C%2FMCZ46.1%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Rediscovery%20and%20a%20Redescription%20of%20the%20Crooked-Acklins%20Boa%2C%20%3Ci%3EChilabothrus%20schwartzi%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%20%28Buden%2C%201975%29%2C%20Comb.%20Nov.%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22R.%20Graham%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Reynolds%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Alberto%20R.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Puente-Rol%5Cu00f3n%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Joseph%20P.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Burgess%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Brian%20O.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Baker%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%2203%5C%2F2018%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.3099%5C%2FMCZ46.1%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220006-9698%2C%201938-2979%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.biodiversitylibrary.org%5C%2Fitem%5C%2F257402%23page%5C%2F1%5C%2Fmode%5C%2F1up%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222021-11-01T09%3A59%3A40Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22MWAJWBEI%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Schwartz%20and%20Henderson%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221985%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3ESchwartz%2C%20A.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Henderson%2C%20R.%20W.%20%281985%29.%20%3Ci%3EA%20guide%20to%20the%20identification%20of%20the%20amphibians%20and%20reptiles%20of%20the%20West%20Indies%20exclusive%20of%20Hispaniola%3C%5C%2Fi%3E.%20Milwaukee%20Public%20Museum.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22A%20guide%20to%20the%20identification%20of%20the%20amphibians%20and%20reptiles%20of%20the%20West%20Indies%20exclusive%20of%20Hispaniola%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Albert%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Schwartz%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Robert%20W.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Henderson%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221985%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22eng%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22978-0-89326-112-2%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-09-16T14%3A19%3A59Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%226QFFGCRZ%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Schwartz%20and%20Henderson%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221991%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3ESchwartz%2C%20A.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Henderson%2C%20R.%20W.%20%281991%29.%20%3Ci%3EAmphibians%20and%20Reptiles%20of%20the%20West%20Indies%3A%20Descriptions%2C%20Distributions%2C%20and%20Natural%20History%3C%5C%2Fi%3E.%20University%20of%20Florida%20Press.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Amphibians%20and%20Reptiles%20of%20the%20West%20Indies%3A%20Descriptions%2C%20Distributions%2C%20and%20Natural%20History%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Albert%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Schwartz%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Robert%20W.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Henderson%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221991%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22978-0-8130-1049-6%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222021-01-12T20%3A39%3A41Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%228JQN59AC%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Schwartz%20and%20Henderson%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221988%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A2%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3ESchwartz%2C%20A.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Henderson%2C%20R.%20W.%20%281988%29.%20West%20Indian%20Amphibians%20and%20Reptiles%3A%20A%20Checklist.%20%3Ci%3EMilwaukee%20Public%20Museum%20Contributions%20in%20Biology%20and%20Geology%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E74%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20264.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.mpm.edu%5C%2Fsites%5C%2Fdefault%5C%2Ffiles%5C%2Ffiles%2520and%2520dox%5C%2FC%2526R%5C%2Flibrary%5C%2Fbio-geo%5C%2F%2523074%2520MPM%2520Contributions%2520in%2520Biology%2520and%2520Geology%2520Number%252074.pdf%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.mpm.edu%5C%2Fsites%5C%2Fdefault%5C%2Ffiles%5C%2Ffiles%2520and%2520dox%5C%2FC%2526R%5C%2Flibrary%5C%2Fbio-geo%5C%2F%2523074%2520MPM%2520Contributions%2520in%2520Biology%2520and%2520Geology%2520Number%252074.pdf%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22West%20Indian%20Amphibians%20and%20Reptiles%3A%20A%20Checklist.%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Albert%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Schwartz%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Robert%20W.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Henderson%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221988%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.mpm.edu%5C%2Fsites%5C%2Fdefault%5C%2Ffiles%5C%2Ffiles%2520and%2520dox%5C%2FC%2526R%5C%2Flibrary%5C%2Fbio-geo%5C%2F%2523074%2520MPM%2520Contributions%2520in%2520Biology%2520and%2520Geology%2520Number%252074.pdf%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222021-01-12T20%3A48%3A26Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22GMXVACUY%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Schwartz%20and%20Thomas%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221975%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3ESchwartz%2C%20A.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Thomas%2C%20R.%20%281975%29.%20A%20check-list%20of%20West%20Indian%20amphibians%20and%20reptiles.%20%3Ci%3ESpecial%20Publication%20of%20the%20Carnegie%20Museum%20of%20Natural%20History%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E1%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20216.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fcarnegiemnh.org%5C%2Fresearch%5C%2Fspecial-publications-of-carnegie-museum%5C%2F%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fcarnegiemnh.org%5C%2Fresearch%5C%2Fspecial-publications-of-carnegie-museum%5C%2F%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22A%20check-list%20of%20West%20Indian%20amphibians%20and%20reptiles.%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22A.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Schwartz%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22R.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Thomas%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221975%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fcarnegiemnh.org%5C%2Fresearch%5C%2Fspecial-publications-of-carnegie-museum%5C%2F%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-08-20T23%3A45%3A12Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22WPYXP4KX%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Sheplan%20and%20Schwartz%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221974%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3ESheplan%2C%20B.%20R.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Schwartz%2C%20A.%20%281974%29.%20Hispaniolan%20boas%20of%20the%20genus%20Epicrates%20%28Serpentes%2C%20Boidae%29%20and%20their%20Antillean%20relationships.%20%3Ci%3EAnnals%20of%20the%20Carnegie%20Museum%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E45%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%2057%26%23x2013%3B143.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Hispaniolan%20boas%20of%20the%20genus%20Epicrates%20%28Serpentes%2C%20Boidae%29%20and%20their%20Antillean%20relationships.%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22B.R.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Sheplan%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22A.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Schwartz%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221974%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-09-13T14%3A42%3A19Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22F9XC9DJD%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Stimson%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221969%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EStimson%2C%20A.%20F.%20%281969%29.%20%3Ci%3EBoidae%20%28Boinae%20%2B%20Bolyeriinae%20%2B%20Loxoceminae%20%2B%20Pythoninae%29.%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%20De%20Gruyter%3B%20%5C%2Fz-wcorg%5C%2F.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Boidae%20%28Boinae%20%2B%20Bolyeriinae%20%2B%20Loxoceminae%20%2B%20Pythoninae%29.%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Andrew%20F.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Stimson%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221969%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22German%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-09-05T16%3A10%3A33Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22QHW3LQDU%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Tolson%20and%20Henderson%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221993%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3ETolson%2C%20P.%20J.%2C%20%26amp%3B%20Henderson%2C%20R.%20W.%20%281993%29.%20%3Ci%3EThe%20natural%20history%20of%20West%20Indian%20boas%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%20%281st%20ed%29.%20R%20%26amp%3B%20A%20Pub.%26%23x202F%3B%3B%20Distributed%20in%20the%20Americas%20by%20Eric%20Thiss%20Serpent%26%23x2019%3Bs%20Tale.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22The%20natural%20history%20of%20West%20Indian%20boas%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Peter%20J.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Tolson%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Robert%20W.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Henderson%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221993%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22978-1-872688-04-6%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-07-23T11%3A45%3A01Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22CWJEARHH%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2129430%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Welch%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221994%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EWelch%2C%20K.%20R.%20G.%20%281994%29.%20%3Ci%3ESnakes%20of%20the%20world%3A%20a%20checklist%3C%5C%2Fi%3E.%20R%20%26amp%3B%20A%20Research%20and%20Information%26%23x202F%3B%3B%20KCM%20Books%20%5Bdistributor%5D.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Snakes%20of%20the%20world%3A%20a%20checklist%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Kenneth%20R.%20G.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Welch%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221994%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22978-1-85913-023-0%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%224E2FHAKS%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-12-22T18%3A52%3A28Z%22%7D%7D%5D%7D Barbour, T. (1937). Third list of Antillean reptiles and amphibians.

Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College. ,

82 , 77–166.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/part/14803 Barbour, T. (1935). A second list of Antillean reptiles and amphibians.

Zoologica : Scientific Contributions of the New York Zoological Society. ,

19 (3), 77–141.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/part/203717 Barbour, T., & Loveridge, A. (1946). First supplement to Typical reptiles and amphibians.

Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College. ,

96 , 59–214.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/part/12098 Barbour, T., & Shreve, B. (1935). Concerning Some Bahamian Reptiles with Notes on the Fauna. Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History , 40 (5), 347–366.

Borroto-Páez, R., & Woods, C. A. (2012). STATUS AND IMPACT OF INTRODUCED MAMMALS IN THE WEST INDIES. In Terrestrial Mammals of the West Indies (pp. 241–257).

Buckner, S. D., Franz, R., & Reynolds, R. G. (2012). BAHAMA ISLANDS AND TURKS & CAICOS ISLANDS. In Island lists of West Indian amphibians and reptiles (Vol. 2, pp. 93–110).

Buden, D. W. (1975). Notes on Epirates chrysogaster (Serpentes: Boide) with the description of a new subspecies. Herpetologica , 31 (2), 166–177.

Buden, D. W. (1974). PREY REMAINS OF BARN OWLS IN THE SOUTHERN BAHAMA ISLANDS. THE WILSON BULLETIN , 86 (4), 336–343.

Central Intelligence Agency. (2021).

The World Factbook .

https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/ Currie, D., Wunderle, J. M., Freid, E., Ewert, D. N., & Lodge, D. J. (2019). The natural history of the Bahamas: a field guide . Comstock Publishing Associates, an imprint of Cornell University Press.

Hedges, S. B., Powell, R., Henderson, R. W., Hanson, S., & Murphy, J. C. (2019). Definition of the Caribbean Islands biogeographic region, with checklist and recommendations for standardized common names of amphibians and reptiles.

Caribbean Herpetology , 1–53.

https://doi.org/10.31611/ch.67 Knapp, C. R., Iverson, J. B., Buckner, S. D., & Cant, S. V. (2011). Conservation Of Amphibians And Reptiles In The Bahamas. In J. Horrocks, B. Wilson, & A. Hailey (Eds.), Conservation of Caribbean Island Herpetofaunas Volume 2: Regional Accounts of the West Indies (pp. 53–88). Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004194083.i-439.21

Maclean, W. P., Kellner, R., & Dennis, H. (1977). Island lists of West Indian amphibians and reptiles.

Smithsonian Herpetological Information Service ,

40 , 1–47.

https://doi.org/10.5479/si.23317515.40.1 Mertens, Robert. (1939). Herpetologische Ergebnisse einer Reise nach der Insel Hispaniola, Westindien. Vittorio Klostermann; /z-wcorg/.

Noble, G. K., & Klingel, G. C. (1932). The reptiles of Great Inagua Island, British West Indies . American Museum of Natural History; /z-wcorg/.

Reynolds, R. G., & Henderson, R. W. (2018). Boas of the World (Superfamily Booidae): A Checklist With Systematic, Taxonomic, and Conservation Assessments.

Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology ,

162 (1), 1–58.

https://doi.org/10.3099/MCZ48.1 Reynolds, R. G., Puente-Rolón, A. R., Burgess, J. P., & Baker, B. O. (2018). Rediscovery and a Redescription of the Crooked-Acklins Boa,

Chilabothrus schwartzi (Buden, 1975), Comb. Nov.

Breviora ,

558 (1), 1–16.

https://doi.org/10.3099/MCZ46.1 Schwartz, A., & Henderson, R. W. (1985). A guide to the identification of the amphibians and reptiles of the West Indies exclusive of Hispaniola . Milwaukee Public Museum.

Schwartz, A., & Henderson, R. W. (1991). Amphibians and Reptiles of the West Indies: Descriptions, Distributions, and Natural History . University of Florida Press.

Schwartz, A., & Henderson, R. W. (1988). West Indian Amphibians and Reptiles: A Checklist.

Milwaukee Public Museum Contributions in Biology and Geology ,

74 , 264.

https://www.mpm.edu/sites/default/files/files%20and%20dox/C%26R/library/bio-geo/%23074%20MPM%20Contributions%20in%20Biology%20and%20Geology%20Number%2074.pdf Schwartz, A., & Thomas, R. (1975). A check-list of West Indian amphibians and reptiles.

Special Publication of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History ,

1 , 216.

https://carnegiemnh.org/research/special-publications-of-carnegie-museum/ Sheplan, B. R., & Schwartz, A. (1974). Hispaniolan boas of the genus Epicrates (Serpentes, Boidae) and their Antillean relationships. Annals of the Carnegie Museum , 45 , 57–143.

Stimson, A. F. (1969). Boidae (Boinae + Bolyeriinae + Loxoceminae + Pythoninae). De Gruyter; /z-wcorg/.

Tolson, P. J., & Henderson, R. W. (1993). The natural history of West Indian boas (1st ed). R & A Pub. ; Distributed in the Americas by Eric Thiss Serpent’s Tale.

Welch, K. R. G. (1994). Snakes of the world: a checklist . R & A Research and Information ; KCM Books [distributor].